OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe the roles of decomposers and microorganisms in nitrogen recycling, and outline the biological and physical processes in the carbon cycle.’

Ecosystem sustainability relies on continuous recycling of nutrients, ensuring essential elements like carbon and nitrogen remain available for living organisms. These cycles interconnect biotic and abiotic components, maintaining ecological balance.

The Role of Recycling in Ecosystems

In natural ecosystems, nutrient recycling prevents the depletion of essential elements. Without it, ecosystems would collapse due to lack of usable forms of nitrogen and carbon. Decomposers and microorganisms are the key biological agents facilitating these processes, converting complex organic materials into simpler inorganic molecules.

Nitrogen Cycle

Importance of Nitrogen

Nitrogen is vital for the synthesis of amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll. Although 78% of the atmosphere is nitrogen gas (N₂), it is inert and cannot be directly used by most organisms. Hence, microorganisms convert nitrogen into biologically usable forms through various processes.

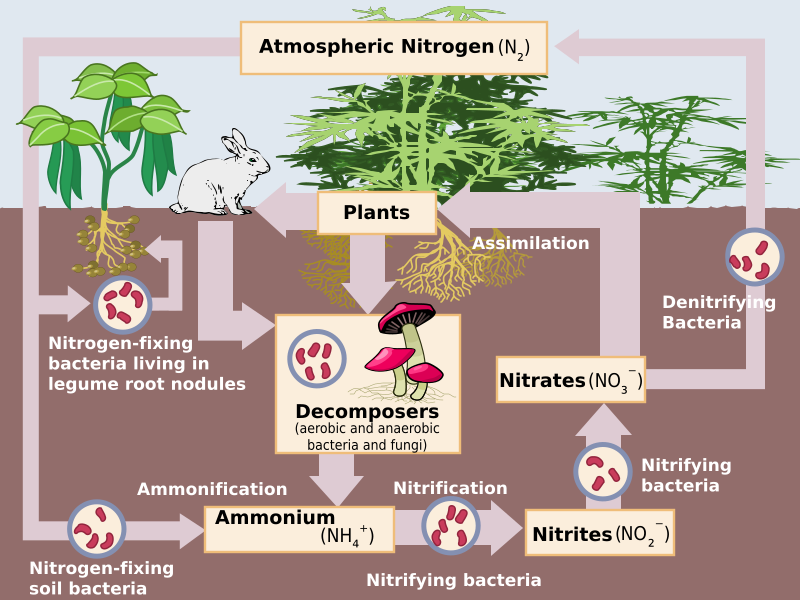

A simplified nitrogen cycle showing nitrogen transformations between atmospheric N₂, soil NH₄⁺, NO₂⁻, and NO₃⁻. Arrows highlight microbial processes in soil and sediments, matching OCR’s required terminology. Source.

Key Stages of the Nitrogen Cycle

1. Nitrogen Fixation

Conversion of atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium ions (NH₄⁺), enabling uptake by plants.

Nitrogen Fixation: The process by which atmospheric nitrogen is converted into ammonia or ammonium ions by microorganisms or industrial means.

Main agents:

Free-living bacteria such as Azotobacter fix nitrogen in soil.

Symbiotic bacteria like Rhizobium live in root nodules of legumes, forming mutualistic relationships.

High-resolution photograph of Medicago (alfalfa) root nodules formed by Rhizobium bacteria. These nodules house nitrogen-fixing bacteroids that convert atmospheric N₂ into NH₃/NH₄⁺, supplying plant-available nitrogen. Source.

Abiotic fixation occurs through lightning or the Haber process.

Importance: Provides plants with usable nitrogen forms, supporting growth in nitrogen-poor soils.

2. Ammonification

When plants and animals die, decomposers such as saprobionts break down organic nitrogen compounds (proteins, nucleic acids, urea) into ammonium ions (NH₄⁺).

Ammonification: The breakdown of organic nitrogen compounds into ammonium ions by decomposer microorganisms.

Organisms involved: Bacillus and Pseudomonas species.

Ecological role: Returns nitrogen to the soil, making it available for nitrifying bacteria.

3. Nitrification

This is the aerobic conversion of ammonium ions into nitrate ions (NO₃⁻) through oxidation. It occurs in two main steps:

Step 1: Nitrosomonas oxidises NH₄⁺ → nitrite ions (NO₂⁻)

Step 2: Nitrobacter oxidises NO₂⁻ → nitrate ions (NO₃⁻)

Plants absorb nitrates via roots for assimilation into amino acids and proteins.

Importance: Ensures nitrogen remains in biologically accessible forms in well-aerated soils.

4. Denitrification

In anaerobic conditions, such as waterlogged soils, denitrifying bacteria (e.g. Pseudomonas denitrificans) reduce nitrates to nitrogen gas (N₂), returning it to the atmosphere.

Denitrification: The reduction of nitrates to nitrogen gas by anaerobic bacteria, resulting in nitrogen loss from soil ecosystems.

Environmental impact: Depletes soil fertility, which is why proper drainage improves crop yield.

Human Influence on the Nitrogen Cycle

Human activities can accelerate or disrupt natural nitrogen cycling:

Fertiliser use: Adds nitrates and ammonium compounds to soil, boosting productivity but risking eutrophication.

Combustion of fossil fuels: Releases nitrogen oxides, contributing to acid rain.

Legume cultivation: Increases biological nitrogen fixation through symbiotic bacteria.

Waste management: Promotes ammonification and denitrification processes in sewage treatment.

Carbon Cycle

Importance of Carbon

Carbon forms the backbone of all organic molecules—carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids—making its recycling essential to life. The carbon cycle links biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere, maintaining global carbon balance.

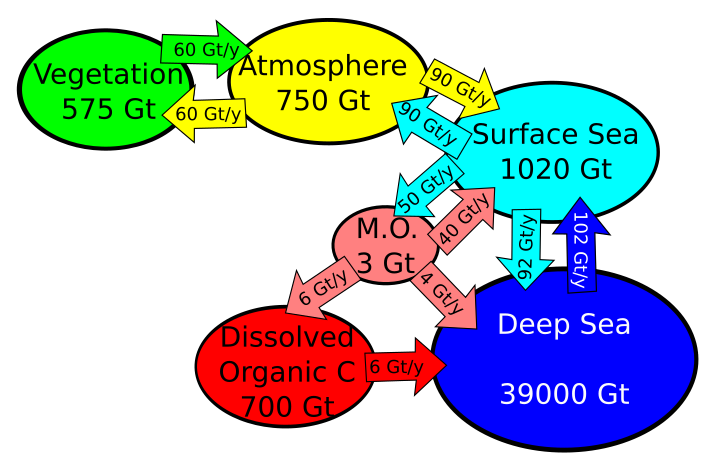

A concise carbon cycle diagram showing carbon exchange between atmosphere, biosphere, oceans, and sediments. Labels identify photosynthesis, respiration, combustion, and sedimentation, aligning precisely with OCR-required processes. Source.

Main Processes in the Carbon Cycle

1. Photosynthesis

Autotrophs such as plants, algae, and cyanobacteria absorb carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere or water and convert it into organic compounds like glucose.

EQUATION

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

Photosynthesis (6CO₂ + 6H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + 6O₂)

CO₂ = Carbon dioxide, gas in the atmosphere

H₂O = Water, absorbed by roots

C₆H₁₂O₆ = Glucose, a carbohydrate storing chemical energy

O₂ = Oxygen, released as a by-product

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

Significance: Transfers carbon from the abiotic to the biotic environment.

2. Respiration

All living organisms respire, releasing CO₂ back into the atmosphere through the breakdown of glucose during aerobic respiration.

Respiration: The metabolic process by which organisms convert biochemical energy from nutrients into ATP, releasing carbon dioxide as waste.

Link to ecosystem: Returns carbon to the atmosphere for reuse in photosynthesis.

3. Decomposition

When organisms die, decomposers (bacteria, fungi, and detritivores) break down organic matter, releasing CO₂ during respiration and returning nutrients to the soil.

Key organisms:

Bacteria and fungi release CO₂ via respiration.

Detritivores (e.g. earthworms) fragment material, increasing surface area for microbial activity.

This process ensures continuous recycling of carbon and nitrogen simultaneously.

4. Combustion

The burning of biomass (wood, fossil fuels) oxidises carbon compounds, releasing large quantities of CO₂ into the atmosphere.

Human impact:

Industrial combustion increases atmospheric CO₂ levels, contributing to global warming and climate change.

Sustainable energy sources aim to balance carbon release with absorption through reforestation.

5. Fossilisation and Sedimentation

In some environments, decomposers cannot fully break down dead organisms due to anaerobic or acidic conditions. Over millions of years, partially decomposed material forms fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas).

Additionally, marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells contribute to sedimentary rocks such as limestone, storing carbon long-term.

Geological processes like volcanic eruptions and weathering slowly return this carbon to the atmosphere as CO₂.

Human Effects on the Carbon Cycle

Human activities alter natural carbon fluxes:

Deforestation: Reduces photosynthetic carbon fixation.

Burning fossil fuels: Accelerates CO₂ emissions beyond natural absorption rates.

Ocean acidification: Increased CO₂ dissolves in oceans, forming carbonic acid, threatening marine ecosystems.

Carbon sequestration: Artificial or natural storage of CO₂ in vegetation or geological formations mitigates greenhouse effects.

Interconnection Between Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles

Both cycles are biogeochemical and rely heavily on microbial activity. Microorganisms act as recyclers, ensuring continuous nutrient availability.

For instance, decomposers releasing CO₂ during decay also generate ammonium for nitrification. Thus, these cycles maintain dynamic equilibrium vital to ecosystem stability and global nutrient balance.

FAQ

Denitrification occurs in anaerobic conditions, such as waterlogged or compacted soils, where oxygen is scarce. Under these conditions, denitrifying bacteria like Pseudomonas denitrificans use nitrate (NO3⁻) instead of oxygen for respiration, converting it into nitrogen gas (N2) or nitrous oxide (N2O).

This process removes available nitrogen from the soil, leading to lower nitrate levels, which reduces the supply of nutrients for plants. Consequently, crop yields may decline unless soils are well-aerated or managed to maintain oxygen levels.

The relationship benefits both partners:

Rhizobium bacteria gain carbohydrates and a protected environment within root nodules.

The legume plant receives a supply of ammonium ions (NH4⁺) produced when the bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2).

This process occurs within specialised nodules containing leghaemoglobin, which maintains a low oxygen concentration, allowing the enzyme nitrogenase to function efficiently. The partnership reduces the need for nitrogen fertilisers in legume crops.

Leghaemoglobin is an oxygen-binding pigment found in legume root nodules, giving them their characteristic pink colour.

It binds free oxygen molecules, maintaining a microaerobic environment that prevents the enzyme nitrogenase from being inhibited by oxygen.

This balance allows respiration to continue for ATP production while enabling nitrogenase to reduce atmospheric N2 into ammonia (NH3) effectively. The ammonia is then assimilated into amino acids, supporting plant growth.

Marine ecosystems play a vital role in both carbon absorption and storage:

Phytoplankton in surface waters absorb CO2 during photosynthesis, forming the base of marine food webs.

When organisms die, carbon in their tissues sinks as marine snow, eventually forming sediments or fossil fuels over geological timescales.

Dissolved CO2 also reacts with seawater to form carbonate and bicarbonate ions, which marine organisms use to build shells and skeletons.

These processes make oceans the largest carbon sink, moderating atmospheric CO2 levels.

Fungi, particularly saprophytic species, release extracellular enzymes that digest complex organic molecules like cellulose, lignin, and proteins.

During this process:

Carbon is released as CO2 through fungal respiration.

Nitrogen is mineralised, forming ammonium ions (NH4⁺) that enter the nitrogen cycle.

Their extensive hyphal networks allow fungi to penetrate organic matter efficiently, speeding up decomposition and ensuring the continual availability of nutrients for primary producers.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Name one biological process that adds ammonium ions (NH4⁺) to the soil and one type of microorganism responsible for converting ammonium ions to nitrates (NO3⁻).

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for correctly naming a process that adds ammonium ions to the soil, e.g. ammonification or nitrogen fixation.

1 mark for identifying a nitrifying bacterium or group that converts ammonium to nitrates, e.g. Nitrosomonas or Nitrobacter.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Describe how microorganisms contribute to the cycling of nitrogen within an ecosystem and explain the importance of these processes for plant growth.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for stating that decomposers or saprobionts break down organic matter into ammonium ions (ammonification).

1 mark for describing nitrification (conversion of NH4⁺ to NO2⁻ and then to NO3⁻) by nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter.

1 mark for mentioning nitrogen fixation (conversion of atmospheric N2 into NH3/NH4⁺) by bacteria such as Rhizobium or Azotobacter.

1 mark for describing denitrification (reduction of nitrates to nitrogen gas) by anaerobic bacteria such as Pseudomonas denitrificans.

1 mark for explaining that these microbial processes provide usable nitrogen compounds (nitrates/ammonium) for plants, which are essential for synthesising amino acids, proteins and nucleic acids, enabling growth.