OCR Specification focus:

‘Outline peptide bond formation, and primary to quaternary structure with key interactions and bonds.’

Proteins are essential biological polymers built from amino acids. Their structure enables highly specific biochemical roles, and changes in bonding or folding can alter function dramatically.

Introduction

Proteins are vital biological macromolecules whose structure determines their diverse functions. Amino acids bond to form polypeptides that fold into complex shapes, producing enzymes, hormones, antibodies and structural components.

Amino acids: monomers of proteins

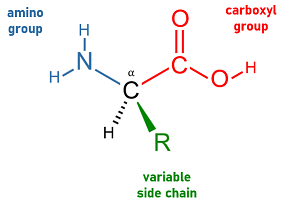

Amino acids are the monomers used to build proteins and all share a basic structure: an amine group, a carboxyl group, a hydrogen atom and a R-group bonded to a central carbon.

Amino acid: The monomer unit of proteins, consisting of an amine group, carboxyl group and variable R-group attached to a central carbon.

The R-group determines each amino acid’s chemical behaviour. There are 20 naturally occurring amino acids, classified as:

Non-polar (hydrophobic)

Polar (hydrophilic)

Charged (acidic or basic)

These differences affect folding and bonding in higher-level protein structures.

A labelled diagram of the general amino acid structure, showing the α-carbon with amine, carboxyl, hydrogen and variable R-group. This clarifies how the constant backbone enables peptide bonding while the R-group determines chemical behaviour. Source.

Forming peptides: condensation and hydrolysis

Amino acids join through condensation reactions, where the amine group of one reacts with the carboxyl group of another, releasing water. The resulting bond is a peptide bond and forms a dipeptide, which can be extended to create polypeptides.

Peptide bond: The covalent bond formed between amino acids during condensation, linking the amine group of one to the carboxyl group of another.

Peptide bonds can be broken by hydrolysis, which uses water to separate amino acids. Ribosomes catalyse peptide formation in living cells, and protease enzymes hydrolyse them during digestion or protein turnover.

Protein structure: four hierarchical levels

The OCR specification requires understanding of primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary structure, along with the key bonds and interactions involved.

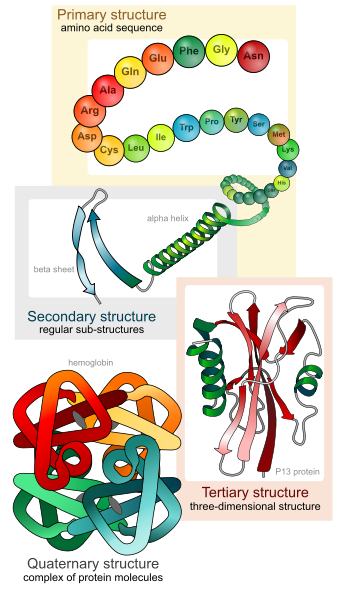

A visual overview of the four structural levels of proteins: amino acid sequence (primary), α-helices and β-sheets (secondary), overall 3-D folding (tertiary) and multi-subunit assembly (quaternary). This reflects the hierarchical structure required by the OCR specification. Source.

Primary structure

Primary structure is the specific sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide. The order is determined by DNA and is held together by peptide bonds only. A single amino acid change can alter folding and function, as seen in haemoglobin disorders.

Secondary structure

Secondary structure arises from hydrogen bonding between amino and carboxyl groups within the polypeptide backbone. The chain forms either:

α-helices: coiled structures stabilised by regular hydrogen bonds

β-pleated sheets: sheet-like arrangements of adjacent strands

Hydrogen bonds provide stability, though these shapes remain relatively flexible.

Tertiary structure

Tertiary structure is the overall three-dimensional shape of a polypeptide. R-group interactions drive folding into a precise configuration essential for function. Key bonding includes:

Hydrogen bonds between polar R-groups

Ionic bonds between charged R-groups

Disulphide bonds (strong covalent bonds between cysteine residues)

Hydrophobic interactions causing non-polar R-groups to cluster away from water

These interactions produce the unique, functional conformation of globular or fibrous proteins.

Quaternary structure

Quaternary structure exists in proteins made of more than one polypeptide chain, such as haemoglobin or collagen. It involves the same bonding as tertiary structure, but between separate subunits. Some quaternary proteins also contain a prosthetic group, for example haem, which is essential for function.

Globular and fibrous organisation

Globular proteins fold into compact, spherical shapes and are soluble due to outward-facing hydrophilic R-groups. They include enzymes, hormones and antibodies.

Fibrous proteins form long, rope-like molecules with repetitive sequences producing strong, insoluble structures such as collagen and keratin.

The relationship between structure and function

The specificity of enzymes and the strength of fibrous proteins both arise from structural features encoded at the primary level and stabilised by the various bonds in higher structures. Disrupting bonding through heat or pH changes can denature proteins by altering shape and preventing function.

Proteins therefore demonstrate a structural hierarchy from amino acid sequence to multi-subunit complexes, with each level stabilised by key bonds and interactions that allow precise roles in biological systems.

FAQ

A single amino acid change can alter the chemical properties of the R-group at that position. This may prevent key bonds from forming, create new interactions or disrupt folding.

If secondary, tertiary or quaternary structure is altered, the protein’s final shape may be different, affecting its function. In enzymes, even one substitution can distort the active site and reduce or stop activity.

Disulphide bonds form strong covalent links between the R-groups of cysteine residues. They are much stronger than hydrogen or ionic bonds.

Because of their strength, they help maintain the protein’s shape under stress, such as changes in temperature or pH. Disulphide bonds are especially common in secreted or structural proteins that must remain stable in challenging environments.

The primary structure influences how R-groups interact during folding. This, in turn, determines whether the final shape is compact or elongated.

Many hydrophilic R-groups on the outside favour globular, water-soluble proteins

Repetitive, non-polar sequences often produce long fibres with strong cross-linking

Fibrous proteins are usually structural, while globular proteins tend to have metabolic or regulatory roles.

Hydrophobic R-groups cluster together inside the protein to avoid contact with water, creating a stable hydrophobic core.

This inward movement helps drive the protein to fold into its final three-dimensional shape. These interactions work alongside hydrogen, ionic and disulphide bonds to maintain the tertiary structure.

Peptide bonds have partial double-bond character due to resonance, preventing free rotation. This makes the bond rigid and planar.

As a result, rotation only occurs around adjacent carbon–carbon or carbon–nitrogen single bonds. This restriction limits possible shapes, helping stabilise regular structures such as alpha helices and beta sheets.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State what is meant by primary structure in a protein and name the type of bond that maintains it.

Question 1 (2 marks total)

Primary structure described as the specific sequence or order of amino acids in a polypeptide (1 mark)

Peptide bonds named as the bonds maintaining the primary structure (1 mark)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Describe how amino acids form a polypeptide and explain how the interactions between R-groups contribute to the tertiary structure of a protein.

Question 2 (5 marks total)

Amino acids joined by a condensation reaction, releasing water (1 mark)

Formation of a peptide bond between the amine group of one amino acid and the carboxyl group of another (1 mark)

Reference to folding into a three-dimensional structure (1 mark)

R-group interactions named (any two: hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, disulphide bonds, hydrophobic interactions) (1 mark)

Explanation that these R-group interactions stabilise the tertiary structure (1 mark)