OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe specialised cells and organisation into tissues, organs and organ systems with examples.’

Cell specialisation and organisation enable multicellular organisms to perform complex biological functions efficiently, through division of labour and structural adaptation at multiple organisational levels.

Cellular Differentiation and Specialisation

Cellular Differentiation

Cellular differentiation is the process by which unspecialised cells become specialised to perform specific functions within an organism. It involves selective gene expression, meaning only certain genes are activated in each cell type, producing proteins that determine structure and function. This allows cells within the same organism to vary greatly in appearance and activity despite having identical DNA.

Differentiation typically occurs during embryonic development but continues throughout life for repair and maintenance in some tissues (e.g. skin, blood).

Specialised Cell: A cell that has developed particular structures and organelles to perform a specific function efficiently.

Characteristics of Specialised Cells

Specialised cells exhibit structural adaptations that support their roles. Examples include:

Red blood cells – contain haemoglobin for oxygen transport; lack a nucleus to maximise space for haemoglobin; biconcave shape increases surface area.

Sperm cells – possess a flagellum for movement, numerous mitochondria to supply ATP for motility, and an acrosome containing enzymes to penetrate the egg.

Root hair cells – have long projections to increase surface area for water and ion absorption and numerous carrier proteins for active transport.

Neurones – extended axons for long-distance electrical transmission and myelin sheaths for insulation.

Guard cells – control stomatal opening via osmotic changes, regulating gas exchange and water loss in plants.

Specialisation leads to a division of labour, ensuring that biological processes are distributed efficiently across cell types.

Hierarchical Organisation of Biological Systems

From Cells to Tissues

A tissue is a group of specialised cells working together to perform a specific function.

Tissue: An aggregation of similar cells that perform a common function within an organism.

Different tissues may contain multiple cell types but are defined by their overall function. In multicellular organisms, tissues represent the first level of structural organisation above individual cells.

Major Animal Tissues

Epithelial tissue – forms linings and coverings.

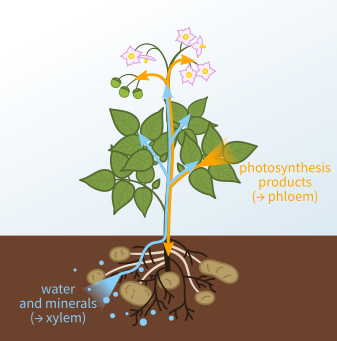

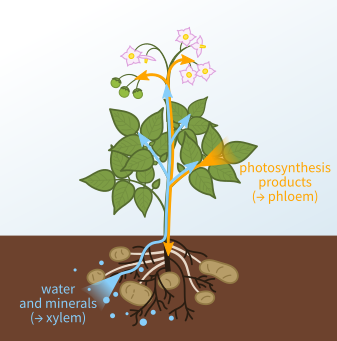

A simplified, colour-coded diagram distinguishing xylem (water and mineral transport) from phloem (translocation of assimilates). This helps visualise complementary transport functions within plant tissues; some source–sink details extend beyond OCR requirements but remain consistent. Source.

Squamous epithelium: thin and smooth; enables rapid diffusion (e.g. alveoli lining).

Ciliated epithelium: contains cilia to move mucus or fluids (e.g. trachea, oviduct).

Connective tissue – supports and binds structures; includes cartilage, bone, and tendons. Contains extracellular matrix with collagen and elastin fibres.

Muscle tissue – contracts to produce movement.

Skeletal (voluntary), smooth (involuntary), and cardiac (heart) muscle types each differ in structure and control.

Nervous tissue – made of neurones and supporting glial cells; specialised for communication and coordination through electrical impulses.

Major Plant Tissues

Epidermal tissue – protective outer layer; secretes waxy cuticle to reduce water loss.

Parenchyma tissue – packing and storage; thin-walled cells that may photosynthesise or provide support.

Collenchyma and sclerenchyma – provide mechanical strength to stems and leaves.

Xylem tissue – conducts water and mineral ions; composed of vessel elements and tracheids, strengthened by lignin.

Phloem tissue – transports organic solutes (e.g. sucrose) via sieve tube elements and companion cells.

A simplified, colour-coded diagram distinguishing xylem (water and mineral transport) from phloem (translocation of assimilates). This helps visualise the complementary roles of the two vascular tissues in transport, aligning with the OCR focus on structure and function. Source.

These tissues collaborate to form plant organs such as roots, stems, and leaves, each with specialised functions.

From Tissues to Organs

An organ consists of several tissues coordinated to carry out one or more specific functions. The interaction of tissues ensures the organ performs efficiently.

Organ: A structure composed of different tissues working together to perform a particular physiological function.

Examples include:

Heart – comprises muscle tissue (contraction), connective tissue (support), and epithelial tissue (lining chambers).

Lungs – consist of epithelial tissue (gas exchange), connective tissue (elasticity), and blood tissue (transport).

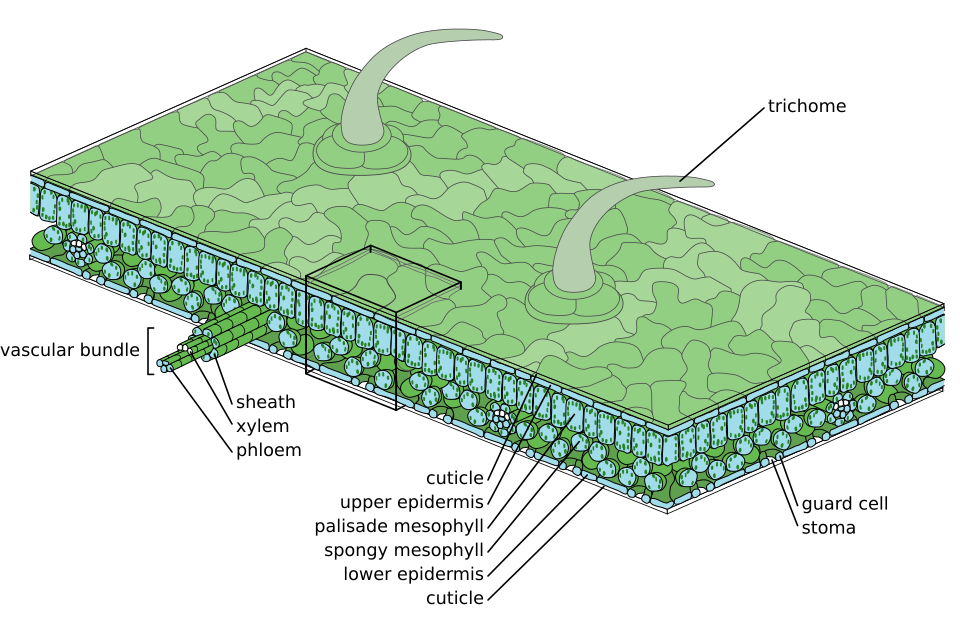

Leaf – includes palisade mesophyll (photosynthesis), xylem and phloem (transport), and epidermis (protection and gas exchange).

Cross-section of a leaf showing upper and lower epidermis, palisade and spongy mesophyll, and vascular tissues (xylem and phloem). This image demonstrates how distinct tissues integrate to form the organ-level structure of the leaf, enabling photosynthesis, transport, and gas exchange. Source.

Each organ’s structure directly supports its function, a key theme in biology known as structure–function relationship.

From Organs to Organ Systems

An organ system comprises several organs working together to perform complex physiological roles essential for survival and homeostasis.

Organ System: A group of organs that interact to perform a major biological function within an organism.

Examples include:

Circulatory system – heart, blood, and vessels working together for oxygen and nutrient transport.

Respiratory system – trachea, bronchi, and lungs enabling gas exchange.

Digestive system – mouth, stomach, intestines, liver, and pancreas cooperating in digestion and absorption.

Skeletal and muscular systems – providing support, movement, and protection.

Plant vascular system – xylem and phloem integrated for water and solute transport.

Integration of Structure and Function

The progression from cell to tissue to organ to system demonstrates increasing levels of organisation, with emergent properties at each stage. For instance:

Individual muscle cells can contract, but coordinated contraction of many cells in muscle tissue produces significant movement.

The heart integrates muscle, nerve, and connective tissues to maintain rhythmic contractions.

At the system level, the cardiovascular system ensures efficient nutrient and gas distribution throughout the body.

In plants, integration between tissues ensures photosynthesis products from leaves are transported to roots and other regions via the vascular system.

This organisational hierarchy underpins biological complexity, allowing multicellular organisms to maintain homeostasis, grow, and respond adaptively to environmental changes through coordinated cellular function.

FAQ

Cell specialisation depends on the selective activation or suppression of genes within a cell’s genome. Although every cell contains the same DNA, different genes are switched on or off depending on internal and external signals, such as hormones or positional information during development.

The active genes produce specific proteins (mainly enzymes and structural proteins) that determine the cell’s structure and function. For instance, a muscle cell activates genes for contractile proteins like actin and myosin, while a pancreatic beta cell activates insulin-producing genes.

When cells differentiate, they lose some of their ability to divide because their genetic material becomes more tightly packed and certain genes become permanently switched off.

This means specialised cells often enter a non-dividing state known as G0. For example, red blood cells lack a nucleus entirely and cannot divide or change function.

Only a few cell types, such as stem cells or some epithelial cells, retain the ability to both divide and differentiate.

Specialisation allows multicellular organisms to operate more efficiently through a division of labour. Each cell type performs one task very well rather than many tasks inefficiently.

Benefits include:

Greater efficiency in metabolism and transport.

Ability to form complex tissues and organs with coordinated functions.

Adaptation to different environmental conditions (e.g. guard cells regulate water loss, nerve cells coordinate responses).

This cooperation among specialised cells enables large, complex organisms to survive and maintain homeostasis.

Coordination between tissues occurs via chemical and electrical signalling systems.

In animals: hormones (endocrine signalling) and nerve impulses coordinate tissue activity. For example, muscle contraction in the heart is synchronised by electrical signals through nervous tissue.

In plants: hormones such as auxins and cytokinins regulate tissue growth and development, while plasmodesmata allow direct communication between cells.

These systems ensure tissues and organs work in harmony to sustain the organism.

The organisation of tissues ensures structural support and functional efficiency. In organs, each tissue plays a complementary role that contributes to the overall function.

In animals: the heart’s muscle tissue contracts to pump blood, connective tissue provides strength, and epithelial tissue lines the chambers to reduce friction.

In plants: the leaf’s palisade mesophyll captures light, spongy mesophyll aids gas exchange, and xylem and phloem handle transport.

Without this coordination, the organ could not perform its specialised role effectively.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain what is meant by the term cell specialisation and give one example of a specialised cell, describing how its structure is related to its function.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for definition: Cell specialisation is when cells develop specific structures to perform particular functions efficiently.

1 mark for appropriate example linked to structure and function, e.g.:

Red blood cell – biconcave shape increases surface area for oxygen uptake / no nucleus allows more space for haemoglobin.

Sperm cell – flagellum for motility / acrosome with enzymes to penetrate egg.

Root hair cell – long projection increases surface area for absorption of water and ions.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Describe how cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems are organised in multicellular organisms, using examples from animals or plants to illustrate your answer.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 5 marks for:

1 mark: Correct hierarchical order stated – cells → tissues → organs → organ systems.

1 mark: Explanation that specialised cells form tissues that work together to carry out a function.

1 mark: Description that organs are made up of several tissues working together for a particular function.

1 mark: Explanation that organ systems consist of multiple organs coordinating to perform major life processes.

1 mark: Use of suitable example(s) – e.g.:

Animal: muscle cells → muscle tissue → heart (organ) → circulatory system (organ system).

Plant: xylem and phloem tissues → vascular bundles → leaf (organ) → plant transport system.