OCR Specification focus:

‘Plants produce defensive chemicals and responses that limit pathogen spread, such as callose deposition and other structural barriers.’

Plants possess a range of defensive responses that prevent or limit infection by pathogens, including structural barriers and chemical defences. These mechanisms collectively ensure plant survival and reduce disease spread.

1. Overview of Plant Defence Mechanisms

Plants lack an immune system comparable to animals, yet they have developed sophisticated physical and chemical strategies to combat pathogens such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protoctists. These defences may be constitutive (always present) or induced (activated in response to attack).

When a pathogen attempts to infect a plant, the initial interaction occurs at the cell surface, triggering recognition of pathogen-associated molecules and subsequent defence responses. The ability to rapidly deploy defences determines whether infection is contained or spreads.

2. Physical and Structural Defences

2.1 Pre-formed Barriers

Plants have structural barriers that provide the first line of defence against pathogen entry:

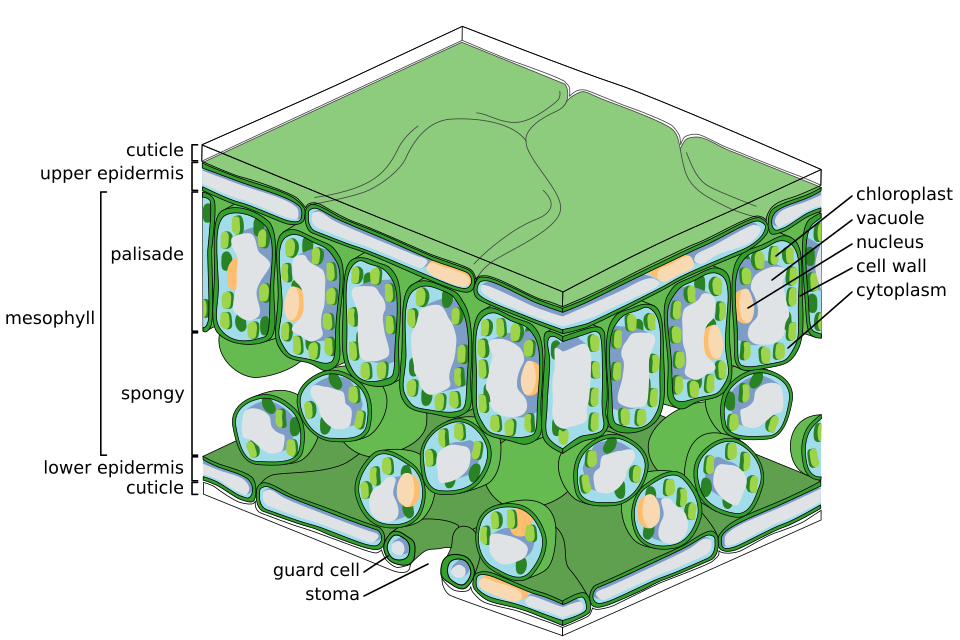

A labelled cross-section of a leaf showing the cuticle, upper and lower epidermis, and guard cells of stomata. These surfaces form physical barriers that reduce pathogen penetration and water accumulation. Vascular tissue is omitted, keeping the focus on protective outer layers; organelles are included but do not exceed syllabus needs. Source.

Waxy cuticle on leaves prevents pathogen penetration and reduces water accumulation, limiting fungal spore germination.

Cell walls composed of cellulose and lignin offer rigidity and act as barriers to enzymatic degradation by pathogens.

Bark and periderm protect stems and woody tissues, impeding microbial access.

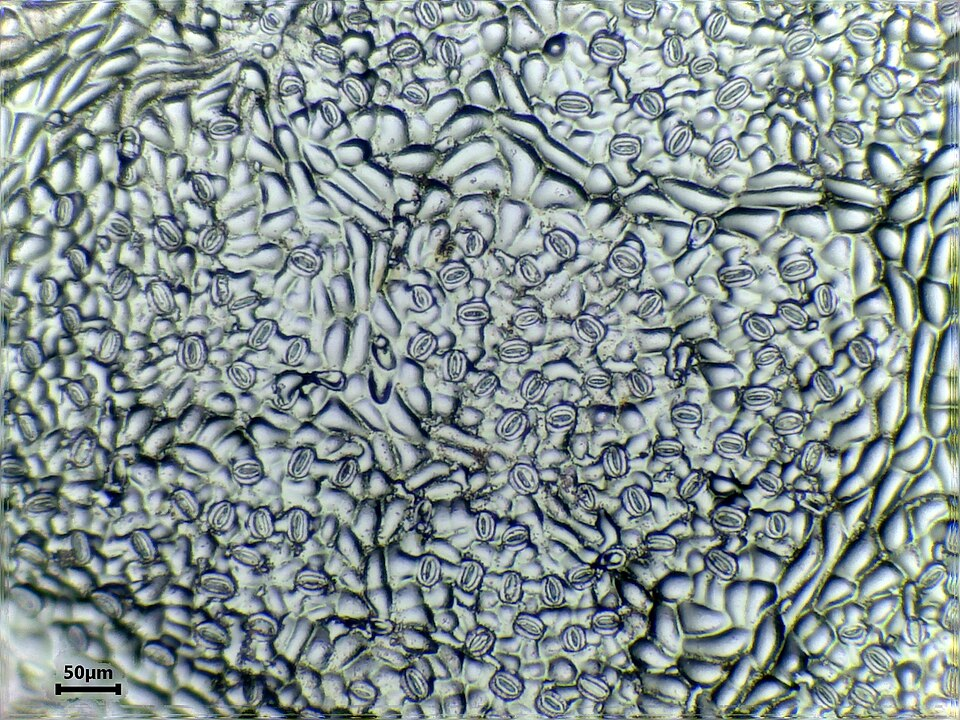

Stomatal closure limits entry of airborne pathogens through leaf pores.

Microscopy image of a leaf epidermal print showing multiple stomata (pores) with guard cells. During attack, plants can close stomata to reduce pathogen ingress, complementing cuticular and epidermal barriers. Educational print; no extraneous annotations beyond subject and magnification (100×). Source.

These barriers are not completely impermeable; when breached, inducible structural changes strengthen the defences.

2.2 Induced Structural Responses

When infection begins, plants reinforce their cell walls and surrounding tissues. Key responses include:

Callose deposition: A polysaccharide called callose is rapidly deposited between the cell membrane and cell wall at sites of pathogen invasion.

This forms a physical barrier that obstructs pathogen spread and strengthens the wall.

Over time, lignin may also be added to further reinforce the structure.

Cell wall thickening around vascular tissues reduces the pathogen’s ability to penetrate or travel through the plant.

Formation of tyloses: Outgrowths from xylem parenchyma cells block xylem vessels, preventing the movement of pathogens through the water transport system.

Callose: A β-1,3-glucan carbohydrate polymer deposited in plant cell walls during stress or infection, acting as a temporary barrier to pathogen entry.

The combined effect of these responses is to contain infection and prevent systemic spread through the plant’s vascular system.

3. Chemical Defences Against Pathogens

3.1 Pre-existing and Induced Chemicals

Plants synthesise a wide range of antimicrobial compounds that deter or destroy invading organisms. These can be:

Pre-existing (constitutive): Continuously produced at low levels to discourage infection.

Induced (active): Synthesised rapidly following pathogen detection, often at the site of invasion.

Important examples include:

Defensins: Small cysteine-rich proteins that disrupt microbial plasma membranes.

Phenols: Compounds such as tannins found in bark and tea leaves that inhibit enzymes used by pathogens to digest cell walls.

Alkaloids: Nitrogen-containing compounds (e.g. caffeine, nicotine) that inhibit metabolic processes in fungi and insects.

Terpenoids: Essential oils and resins that possess antifungal or antibacterial properties.

Hydrolytic enzymes: Enzymes such as chitinases (which break down fungal cell walls) and glucanases (which degrade polysaccharides in pathogen walls).

These substances may also signal nearby cells to activate further defences.

3.2 Phytoalexins

Phytoalexins are antimicrobial secondary metabolites produced de novo in response to pathogen attack. They accumulate around the infection site and act by inhibiting pathogen metabolism or damaging cell membranes.

Phytoalexins: Antimicrobial compounds synthesised by plants in response to pathogen invasion, limiting infection by interfering with pathogen growth and reproduction.

This localised chemical warfare ensures that only the affected area mounts an energetic response, conserving resources for growth and reproduction elsewhere in the plant.

4. Detection and Signalling in Plant Defence

4.1 Pathogen Recognition

Plants detect pathogens through recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as flagellin or chitin fragments, via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the plant cell membrane.

Upon recognition, cell signalling pathways are activated, leading to transcription of defence genes and synthesis of protective compounds. This early detection system allows a swift response to infection.

4.2 Cell Signalling and Systemic Responses

Once local defences are triggered, plants often initiate systemic signalling, ensuring that distant tissues are primed for attack. Signalling molecules include:

Salicylic acid, associated with systemic acquired resistance (SAR) — a long-lasting increase in the plant’s defensive capability.

Jasmonic acid, which mediates wound and insect responses, stimulating synthesis of toxic or deterrent chemicals.

Ethylene, a gaseous hormone that coordinates responses such as leaf abscission and the production of defensive enzymes.

These signalling networks ensure the plant acts as a coordinated system rather than a collection of independent cells.

5. Examples of Defensive Responses

5.1 Callose and Lignin Reinforcement

During fungal infection, such as powdery mildew in cereals, plants deposit callose at the sieve plates in phloem to block transmission. Lignin is later added to provide permanent strengthening, turning the temporary callose barrier into a lasting wall.

5.2 Production of Defensive Chemicals

When tobacco plants are infected with Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV), they produce specific phenolic compounds that inhibit viral replication. Similarly, potato plants attacked by Phytophthora infestans (late blight) release hydrolytic enzymes and deposit callose, isolating infected tissues.

5.3 Necrosis

In some cases, plants deliberately induce cell death around the infection site, creating a necrotic zone that deprives pathogens of nutrients and confines infection. This is a key aspect of hypersensitive response in plants.

6. Integration of Plant Defence Strategies

Plant defence involves a complex integration of physical barriers, chemical responses, and cellular signalling. Once an infection is detected, a cascade of defensive mechanisms — from callose deposition to antimicrobial secretion — limits the pathogen’s ability to spread. The efficiency of these mechanisms underpins plant health and resilience against disease.

FAQ

Plants detect pathogens through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) located on their cell membranes. These receptors recognise pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as fragments of fungal cell walls or bacterial flagellin.

Once recognised, this interaction triggers PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), which activates intracellular signalling cascades. The result is the production of defensive chemicals, strengthening of cell walls, and expression of defence-related genes, all occurring before physical symptoms appear.

Callose is deposited rapidly at the site of infection to seal off weakened cell walls and restrict pathogen entry. However, it is relatively soft and can degrade over time.

Plants later reinforce these regions with lignin or other durable materials, providing long-term mechanical strength.

Therefore, callose acts as an emergency barrier, buying time for the plant to establish more permanent structural defences.

Phytoalexins are induced compounds, produced only after pathogen detection. They inhibit pathogen growth through toxicity or by interfering with pathogen metabolism.

Phytoanticipins are pre-formed antimicrobial chemicals, present before infection occurs and stored in plant tissues in inactive forms.

Both act as chemical defences, but their timing and mode of production differ — phytoalexins are reactive, while phytoanticipins are preventative.

Environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and light affect both pathogen activity and the plant’s ability to maintain barriers.

High humidity can soften the cuticle, increasing susceptibility to fungal infection.

Low temperatures can slow down the plant’s metabolic rate, delaying defence responses.

Adequate light and nutrient levels support energy-intensive processes like callose synthesis and lignification, enhancing overall resistance.

Thus, environmental balance is crucial to maintain optimal structural integrity against pathogens.

After pathogen recognition, signalling molecules spread messages throughout the plant to coordinate defence.

Key molecules include:

Salicylic acid – triggers systemic acquired resistance (SAR), leading to heightened defences in uninfected tissues.

Jasmonic acid – promotes local defence responses, especially against insect herbivory and wounding.

Ethylene – works synergistically with other hormones to regulate defensive gene expression.

These compounds ensure that both the infected area and distant tissues respond appropriately to threat.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (3 marks)

Describe two structural defences that plants use to prevent pathogen entry and explain how each provides protection.

Mark scheme:

Waxy cuticle mentioned (1 mark)

Explanation: acts as a physical barrier preventing water accumulation and entry of pathogens such as fungi (1 mark)

Cell wall or lignin reinforcement mentioned (1 mark)

Explanation: provides rigidity and resistance to enzymatic degradation by pathogens (1 mark)

Maximum 3 marks — credit any two appropriate structural defences with correct explanations.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain the role of induced plant responses in preventing the spread of pathogens once infection has begun. Include reference to callose deposition and chemical defences.

Mark scheme:

Callose deposition correctly described as forming between cell membrane and cell wall at infection sites (1 mark)

Function of callose: acts as a temporary barrier to pathogen entry or strengthens the wall (1 mark)

Lignin reinforcement of callose layers mentioned or described (1 mark)

Reference to chemical defences such as phytoalexins, defensins, phenols, or enzymes that inhibit pathogen growth (1 mark)

Explanation that these defences limit pathogen spread or contain infection locally (1 mark)

Maximum 5 marks — award full credit for accurate terminology and clear links between process and function.