OCR Specification focus:

‘Explain roles of NAD, FAD and coenzyme A; oxidative phosphorylation with electron carriers, oxygen and mitochondrial cristae.’

Energy release in respiration relies on the transfer of electrons through coenzymes and membrane systems. Coenzymes and oxidative phosphorylation together enable efficient ATP production in cells.

The Role of Coenzymes in Respiration

Coenzymes are non-protein organic molecules that assist enzymes in catalysing oxidation–reduction reactions. They act as electron and hydrogen carriers, temporarily accepting or donating atoms during respiration.

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD)

NAD is a key coenzyme derived from vitamin B₃ (niacin). It functions primarily in dehydrogenation reactions during glycolysis, the link reaction, and the Krebs cycle.

NAD: A coenzyme that accepts hydrogen atoms (as a proton and an electron pair) to form reduced NAD (NADH), later releasing them for ATP synthesis during oxidative phosphorylation.

In each stage of aerobic respiration before oxidative phosphorylation:

Glycolysis: Two molecules of reduced NAD are produced when triose phosphate is oxidised to pyruvate.

Link reaction: Pyruvate is dehydrogenated and decarboxylated, generating one reduced NAD per pyruvate.

Krebs cycle: Several dehydrogenation steps yield reduced NAD as hydrogen atoms are removed from intermediates.

Each reduced NAD (NADH) delivers high-energy electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC) in the mitochondrial inner membrane, where they drive ATP synthesis.

Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD)

FAD, derived from riboflavin (vitamin B₂), is another coenzyme with a similar role to NAD but specific to certain enzymes within the Krebs cycle.

FAD: A coenzyme that accepts two hydrogen atoms to form reduced FAD (FADH₂), transferring its electrons to the electron transport chain at a later entry point than NADH.

Key distinctions between NAD and FAD:

FAD is reduced during the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the Krebs cycle.

FADH₂ donates electrons directly to the second carrier protein in the ETC, contributing less to proton pumping than NADH.

Consequently, FADH₂ yields fewer ATP molecules per molecule oxidised compared to NADH.

Coenzyme A (CoA)

Coenzyme A plays a central role in linking glycolysis and the Krebs cycle through the transport of acetyl groups.

Coenzyme A (CoA): A coenzyme that combines with acetate (from pyruvate) to form acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which delivers the acetyl group into the Krebs cycle.

Functions of CoA include:

Forming acetyl-CoA during the link reaction when pyruvate is decarboxylated.

Carrying acetyl groups to the first stage of the Krebs cycle, where they combine with oxaloacetate to form citrate.

Acting as a transporter for fatty acid metabolism, linking carbohydrate and lipid catabolism.

Oxidative Phosphorylation

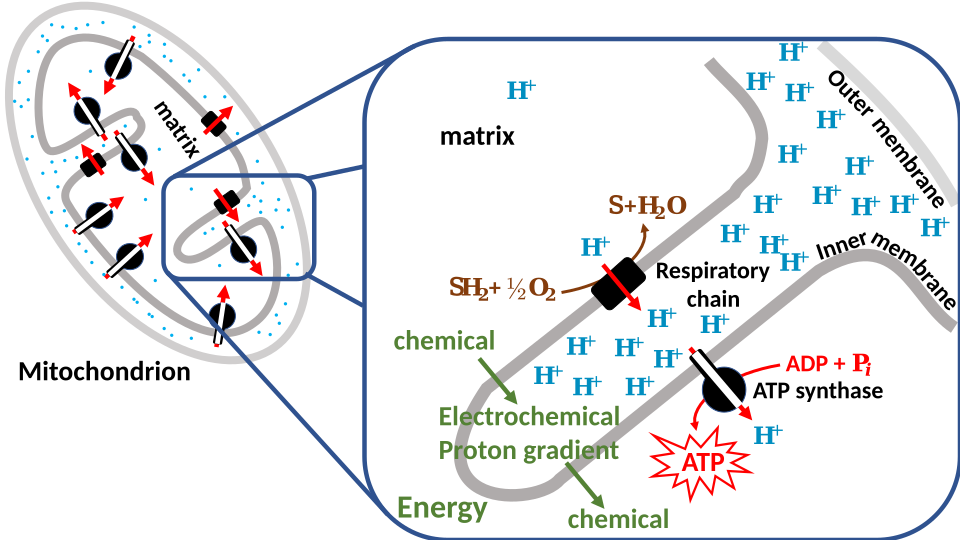

Oxidative phosphorylation is the final stage of aerobic respiration and the main source of ATP. It occurs in the inner mitochondrial membrane, which is folded into cristae to increase surface area for the necessary enzymes and carriers.

Overview of the Process

The process involves the transfer of electrons from reduced NAD and FAD through a sequence of electron carrier proteins, culminating in the reduction of oxygen to water.

Key stages:

Electron Donation

Reduced NAD and FAD are oxidised, releasing hydrogen atoms.

Each hydrogen atom splits into a proton (H⁺) and an electron (e⁻).

Electrons enter the electron transport chain (ETC) located in the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Electron Transport Chain (ETC)

The ETC consists of a series of electron carriers (mainly cytochromes) embedded within the membrane.

As electrons pass from one carrier to the next, they lose energy.

This energy is used to pump protons from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space.

Proton Gradient Formation

The active transport of H⁺ ions establishes an electrochemical gradient (proton motive force).

The intermembrane space becomes acidic and positively charged, while the matrix remains negatively charged.

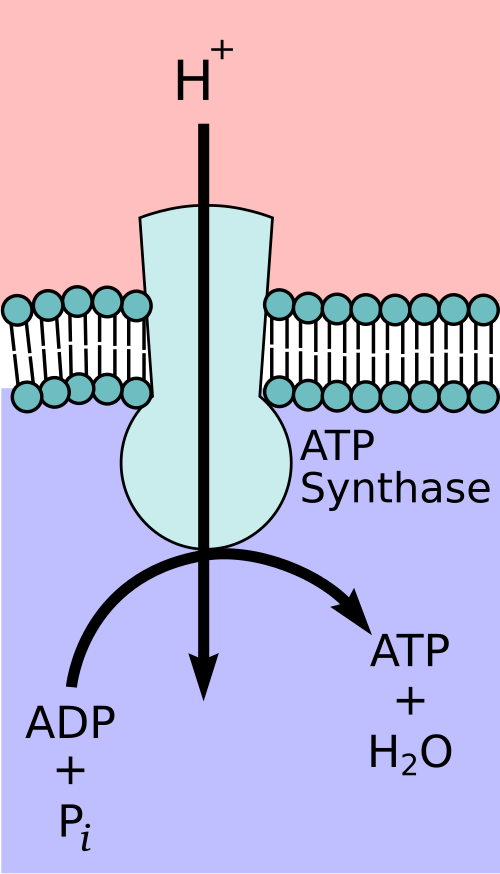

ATP Synthesis via ATP Synthase

Protons move back into the matrix through ATP synthase, a large enzyme complex spanning the inner membrane.

The flow of protons drives the rotation of ATP synthase, catalysing the condensation of ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) to form ATP.

Diagram of F₀F₁-ATP synthase, highlighting the membrane-embedded F₀ channel that conducts H⁺ and the F₁ catalytic head that forms ATP from ADP + Pi. The layout clarifies how proton flow couples to conformational changes that drive phosphorylation. Extra molecular subunit naming beyond OCR depth is minimal and does not distract from the core idea. Source.

EQUATION

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

ATP Synthesis (Chemiosmosis) = ADP + Pi → ATP

ADP = Adenosine diphosphate, a nucleotide with two phosphate groups

Pi = Inorganic phosphate group

ATP = Adenosine triphosphate, the universal energy currency of cells

—-----------------------------------------------------------------

This process of ATP formation driven by a proton gradient is known as the chemiosmotic mechanism, described by Peter Mitchell.

Schematic of chemiosmotic coupling in mitochondria, showing electrons moving along carrier proteins in the inner membrane as protons are pumped to create an electrochemical gradient. Protons flow back through ATP synthase, driving ADP + Pi → ATP. This image is limited to the core mechanism and avoids extraneous pathway detail. Source.

The Role of Oxygen

Oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor in the chain, ensuring the continuation of electron flow.

At the end of the ETC, oxygen combines with electrons and protons to form water.

Without oxygen, electrons would accumulate in the chain, halting NAD and FAD oxidation, and therefore stopping ATP production.

Final Electron Acceptor: A molecule that accepts the terminal electrons from the electron transport chain, allowing continued electron flow; in aerobic respiration, this is molecular oxygen (O₂).

The Importance of the Mitochondrial Cristae

The cristae of the mitochondria are essential structural adaptations for oxidative phosphorylation:

Provide a large surface area for electron carriers and ATP synthase complexes.

Facilitate efficient proton pumping and ATP generation.

Contain embedded proteins for NADH dehydrogenase and cytochrome oxidase activity.

ATP Yield

Each reduced NAD typically yields around three ATP molecules, whereas each reduced FAD yields around two ATP molecules. The difference arises because FAD enters the chain later, contributing less to the proton gradient.

Significance of Oxidative Phosphorylation

Produces the majority of cellular ATP required for processes such as active transport, biosynthesis, and muscle contraction.

Links metabolic pathways by regenerating oxidised coenzymes (NAD⁺ and FAD) for reuse in glycolysis and the Krebs cycle.

Maintains aerobic energy balance, ensuring efficient respiration in mitochondria.

FAQ

FADH₂ donates its electrons to Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase), which bypasses the first proton-pumping step at Complex I.

As a result, fewer protons are moved into the intermembrane space compared with NADH oxidation. This smaller proton gradient drives less ATP production.

On average, FADH₂ produces about two ATP molecules, while NADH yields around three because NADH donates electrons earlier in the chain, enabling more proton pumping.

ATP in oxidative phosphorylation is not formed directly by enzyme-catalysed substrate conversion.

Instead, the energy released from electron transfer in the electron transport chain is first used to build a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane.

The proton gradient then drives ATP synthase, which catalyses ADP + Pi → ATP. Hence, ATP is produced indirectly through energy coupling rather than a direct chemical reaction.

If the inner membrane lost its impermeability, protons would diffuse back into the matrix freely rather than through ATP synthase.

This would collapse the proton motive force, preventing chemiosmosis and ATP synthesis.

Although electron transport and oxygen consumption might still occur temporarily, energy would be released as heat, not ATP, leading to inefficient respiration.

Some toxins interfere with specific complexes in the electron transport chain:

Cyanide binds to cytochrome oxidase (Complex IV), preventing electron transfer to oxygen.

Rotenone inhibits Complex I, blocking NADH oxidation.

Oligomycin inhibits ATP synthase, stopping proton flow and ATP production.

These disruptions halt ATP formation and can cause cell death because coenzymes remain reduced and respiration cannot continue.

Mitochondria contain mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and 70S ribosomes, allowing them to synthesise some of their own proteins and enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation.

This includes certain electron transport chain subunits and ATP synthase components embedded in the inner membrane.

Having their own genetic system enables mitochondria to respond rapidly to energy demands by producing these proteins without relying entirely on nuclear DNA.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State the role of oxygen in oxidative phosphorylation.

Mark scheme:

Oxygen acts as the final electron acceptor in the electron transport chain (1)

It combines with electrons and protons to form water (H₂O) (1)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Describe how reduced NAD and reduced FAD are used in oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP.

Mark scheme:

Reduced NAD and FAD are oxidised, releasing hydrogen atoms (1)

Each hydrogen atom splits into a proton (H⁺) and an electron (e⁻) (1)

Electrons pass along the electron transport chain on the inner mitochondrial membrane, losing energy at each carrier (1)

The released energy is used to pump protons into the intermembrane space, creating a proton gradient (1)

Protons move back through ATP synthase, driving the synthesis of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) (1)

(Additional credit point) Oxygen accepts the electrons and protons at the end of the chain to form water, allowing the process to continue (1)