AP Syllabus focus:

‘Apply the definition of continuity at a point to justify whether functions, including piecewise-defined functions, are continuous or have discontinuities at given points.’

Introducing continuity at a point requires linking formal limit behavior to actual function values, helping students determine precisely when a function behaves smoothly or exhibits a discontinuity.

Determining Continuity Using the Three-Part Definition

To justify continuity or discontinuity at a point, AP Calculus AB students must apply the formal definition, which establishes when a function behaves predictably near a specified input value.

Continuity at a Point: A function is continuous at if (1) exists, (2) exists, and (3) .

This definition allows us to evaluate whether behavior near a point aligns with the actual function value, ensuring there is no jump, hole, or infinite behavior at that point.

Condition 1: Existence of the Function Value

The first requirement checks whether the function is even defined at the point of interest. Without a defined function value, continuity is impossible.

Confirm the function has an assigned output at the specific input.

Identify any missing values or excluded inputs.

Recognize that undefined points often signal removable or infinite discontinuities, depending on limit behavior.

A missing function value indicates the graph cannot pass smoothly through the point, motivating further inspection of how the limit behaves nearby.

Condition 2: Existence of the Limit at the Point

The second requirement ensures the function approaches a single predictable value from both sides as gets arbitrarily close to .

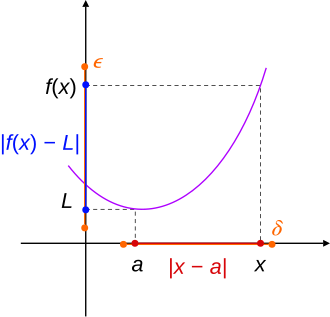

This graph illustrates a function whose values approach a single limit as approaches a point from both sides. The shaded neighborhoods visualize how restricting controls . The ε–δ notation shown exceeds AP Calculus AB requirements but supports the same conceptual idea. Source.

Limit at a Point: The limit exists if the left-hand limit and right-hand limit both exist and are equal.

A function may be defined at , yet still be discontinuous if nearby values do not settle toward a common number.

Condition 3: Agreement Between Function Value and Limit

The final requirement checks whether the limit matches the actual function value. Even if both exist individually, continuity is broken when they differ.

If , the function displays a removable discontinuity, since redefining the value could restore continuity.

If , the function passes the final test for continuity at the point.

This alignment ensures the graph does not suddenly jump or break at .

Applying the Definition to Justify Continuity

To justify continuity rigorously, each condition must be addressed explicitly. Students should articulate how limit behavior and defined values interact to produce smooth or disrupted function behavior.

Structured Approach for Justification

When analyzing any function, especially piecewise-defined functions, use this sequence:

Identify the point and check whether is defined.

Evaluate the left-hand and right-hand limits to determine whether a common limit exists.

Compare the limit value with the function value.

Conclude continuity or discontinuity based on which conditions fail.

This logical structure mirrors the AP expectation that students reason from foundational definitions rather than relying on intuition alone.

Continuity in Piecewise-Defined Functions

Piecewise functions require special attention at boundary points where the formula changes. Justification must consider how each piece behaves as inputs approach the transition point.

Piecewise Continuity Requirement: For a piecewise function to be continuous at a boundary point, the boundary value must be defined and match the common one-sided limit from both pieces.

Because each segment may exhibit different algebraic forms, determining continuity requires comparing their limiting behaviors as approaches the shared boundary.

Identifying Types of Discontinuities Through the Definition

The definition not only determines whether continuity holds but also classifies the type of discontinuity when it fails.

Removable Discontinuities

A removable discontinuity occurs when the limit exists but does not match the function value, or when the function value is missing entirely even though the limit is well-defined.

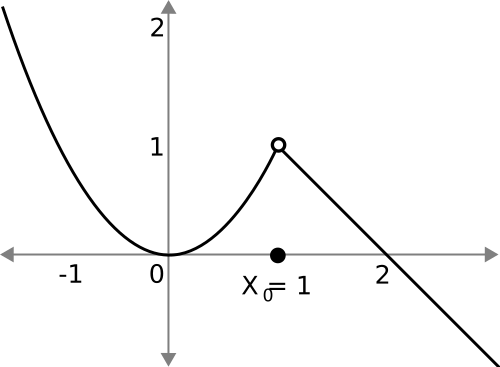

This graph shows a smooth function with an open circle indicating a removable discontinuity. The limit follows the curve even though the function value is missing or mismatched. The minimal labeling focuses attention on the discontinuity itself. Source.

The graph shows a hole at the point.

Redefining the value can restore continuity.

These arise frequently in rational expressions after canceling common factors.

Jump Discontinuities

A jump discontinuity occurs when left-hand and right-hand limits exist but differ.

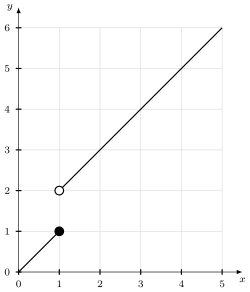

This figure depicts a piecewise-defined function whose one-sided limits disagree at , creating a jump discontinuity. The open and closed circles highlight differing function values on each side. The explicit function definitions shown on the Commons page are an example rather than required AP content. Source.

Graphically, the function “jumps” from one value to another.

Common in piecewise contexts where formulas disagree at the boundary.

Infinite Discontinuities

An infinite discontinuity occurs when the function grows without bound near the point, producing an infinite limit or no meaningful limiting behavior.

Associated with vertical asymptotes.

Neither limit nor function value is finite, violating continuity at multiple definition levels.

Justifying Continuity in Practice

To meet AP expectations, students must reference all three definition components when constructing written justifications. Statements should describe clearly: the existence or nonexistence of , the behavior of , and whether the two align. This methodical approach ensures precise reasoning grounded in formal calculus language.

FAQ

A graph can make continuity appear obvious, but it is not a proof. Visual impressions can hide subtle behaviour, especially near sharp curves or points.

The formal definition requires verifying three precise conditions, ensuring your argument is valid even when the function is not neatly drawn or when its behaviour is not immediately visible from a graph.

A limit describes nearby behaviour only, not the actual function value at the point.

A function can have a well-defined limit at a point but be discontinuous if the function value does not exist or does not match that limit.

This distinction prevents assumptions based solely on approaching values.

You must examine both pieces of the definition.

To justify continuity at a boundary:

• Show the left-hand and right-hand limits exist.

• Demonstrate that these limits are equal.

• Confirm that the shared value equals the defined function value at the boundary.

Different discontinuities reveal which part of the definition fails.

• A removable discontinuity indicates the limit exists but the function value is incorrect or missing.

• A jump discontinuity shows the one-sided limits differ.

• Infinite discontinuities occur when at least one one-sided limit diverges.

This helps structure a clear explanation.

Yes. Both one-sided limits may be finite yet still unequal.

If the left-hand and right-hand limits do not match, the overall limit does not exist, and the function is automatically discontinuous at that point, even if the function is defined there.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

A function g is defined as follows:

g(x) = x + 2 for x not equal to 3, and g(3) = 10.

Determine whether g is continuous at x = 3, giving a reason for your answer.

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly states whether the function is continuous or discontinuous at x = 3.

• 1 mark: Shows that the limit of g(x) as x approaches 3 is 5.

• 1 mark: Explains that the limit (5) does not equal g(3) (which is 10), so continuity fails.

Full correct answer: g is not continuous at x = 3 because the limit as x approaches 3 is 5, but the function value at x = 3 is 10, so they do not match.

(4–6 marks)

A piecewise-defined function h is given by:

h(x) = 2x − 1 for x less than or equal to 2

h(x) = kx + 4 for x greater than 2

(a) Find the value of k for which h is continuous at x = 2.

(b) Explain how the three-part definition of continuity justifies your answer in part (a).

(4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Correctly evaluates the left-hand limit as x approaches 2, giving 3.

• 1 mark: Sets the continuity condition 3 = 2k + 4.

• 1 mark: Solves to obtain k = −1/2.

(b)

• 1 mark: States that h(2) exists because the first piece defines h at x = 2.

• 1 mark: States that the limit from the left and right both exist and are equal when k = −1/2.

• 1 mark: Concludes that continuity holds because the common limit equals the function value at x = 2.

Full correct answer: k = −1/2, and continuity is justified because the function value at 2 exists, the left-hand and right-hand limits agree at 3, and this common limit equals the defined value h(2).