AP Syllabus focus:

‘Recognize that many applied rate-of-change problems share the same underlying derivative structure, even when the contexts, units, and variable names look very different.’

Many applied rate-of-change questions across science, economics, and geometry rely on the same underlying derivative relationships, even when surface details appear unrelated or highly specialized.

Understanding Structural Similarity in Rate-of-Change Problems

Although applied contexts differ widely, most rate-of-change problems hinge on expressing how one quantity depends on another and then interpreting the derivative structure that emerges. Students often focus on story details—such as populations, prices, lengths, or chemical concentrations—but the calculus remains governed by the same principles of instantaneous change.

The essential idea is that whenever a quantity varies with respect to an independent variable, its derivative captures the instantaneous rate of that change.

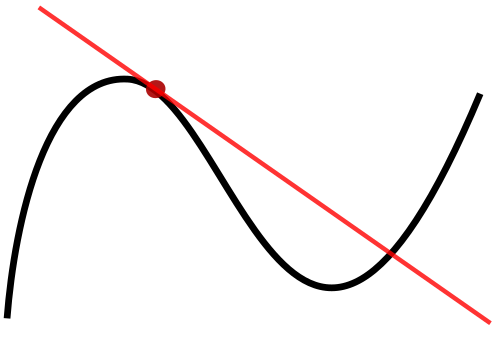

This diagram shows a curve with a tangent line touching the graph at a single point. The slope of the tangent line represents the instantaneous rate of change of the function with respect to at that point. The image is purely structural, without any specific context, making it an ideal reference for comparing how the same derivative idea appears in many applications. Source.

To identify this shared structure, it is important to recognize that a rate of change is simply a ratio describing how quickly one variable responds as another changes.

Rate of Change: The derivative describing how one quantity changes with respect to another in an applied context.

In many non-motion contexts, the independent variable is time, but structural similarities appear even when the independent variable is cost, volume, or another physical or conceptual measure. Recognizing this unity helps simplify complex-looking problems.

Identifying Common Components Across Contexts

Even when variable names differ, rate-of-change problems share several predictable components:

A dependent variable whose behavior is being examined.

An independent variable with respect to which the rate is measured.

A functional relationship connecting these variables.

A derivative that expresses instantaneous change in the relationship.

Because these features recur across fields, the calculus tools remain consistent.

Interpreting the Derivative Regardless of Context

The derivative’s meaning must always be interpreted according to the situation. The statement “ represents the instantaneous rate of change of with respect to ” remains valid whether describes population size, the area of a square, or profit in a business model. The derivative always answers: How fast is the output changing at this instant, given a marginal change of the input?

When these ideas are framed in varied real-world settings, they remain structurally identical because the derivative keeps its mathematical meaning even while units and variables change.

Units as a Structural Identifier

Units often reveal the underlying structure of a related rate problem, because the derivative always expresses a “per-unit change” in measurable terms.

Compound Units: Derived units formed by dividing the units of the dependent variable by those of the independent variable to express a rate of change.

Compound units—such as “people per year,” “dollars per unit,” or “square centimeters per second”—signal that the problem relies on a derivative, even if the surrounding scenario appears unfamiliar. A consistent method emerges: identify what is changing, identify with respect to what it is changing, and link them using derivative notation.

A normal sentence ensures continuity and reinforces that unit analysis provides insight into how variables interact structurally.

Rewriting Relationships in Multiple Contexts

Different applied contexts often share the same underlying functional forms. For example, a cost function in economics, a concentration function in chemistry, and a geometric function for surface area may all be modeled by expressions whose derivatives describe marginal change. Because of this, rates from unrelated fields follow parallel processes for differentiation, interpretation, and communication.

Students often focus on story details—such as populations, prices, lengths, or chemical concentrations—but the calculus remains governed by the same principles of instantaneous change.

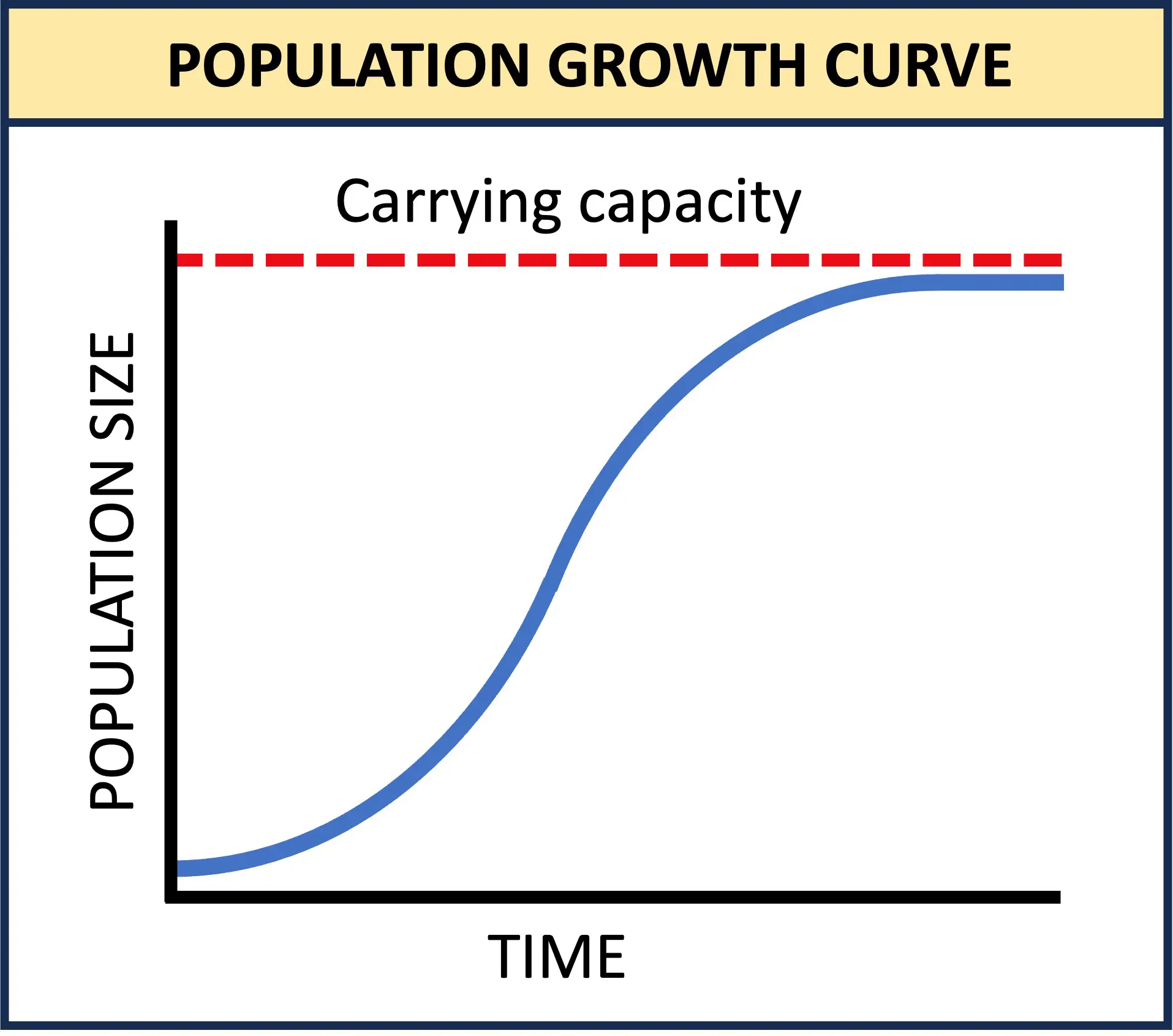

This graph shows a population growth curve over time, with population size on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis. The curve illustrates how a biological population changes over time, highlighting that population level is a dependent variable whose rate of change can be studied with derivatives. The dashed carrying-capacity line is additional ecological detail not required in the syllabus, but it helps contextualize biological rate-of-change structures. Source.

To support this viewpoint, many problems use relationships expressible as formulas involving powers, products, or compositions, all of which require familiar differentiation rules.

= Dependent quantity measured in appropriate units

= Independent variable, often representing time

A single sentence between equation blocks emphasizes that the functional form remains recognizable across scenarios, even when symbols and contexts vary.

Seeing the Unity Behind Diverse Applications

Understanding structural similarity means noticing patterns rather than memorizing formulas for every situation. Across biology, economics, physics, and geometry, the derivative expresses:

Instantaneous response of one quantity to another.

Local linear behavior, allowing interpretation of small changes.

Marginal effects, describing incremental impacts in a system.

Dynamic relationships, where changes influence other changes.

In all these settings, the steps students take remain consistent:

Identify the variables and their units.

Determine how quantities depend on one another.

Translate the relationship into function or derivative notation.

Interpret the derivative using context-specific language.

Recognize that mathematical structure persists even when variable names change.

FAQ

Look for the pattern of one quantity depending on another in a differentiable way. If a problem describes how one variable changes as another varies, it likely shares the same structure.

Check for clues such as:

• A dependent variable described as “changing with” another variable

• Units that appear as “something per something”

• A context requiring an instantaneous, not averaged, change

When these features align, the mathematical treatment mirrors other rate-of-change problems even if the real-world settings differ.

Time is universally measurable and often the natural driver of change, making it a convenient independent variable across disciplines.

However, time is not required. Any variable that a quantity depends on can play the independent role, such as cost, volume, or distance.

Recognising this flexibility helps in spotting structural similarities between problems that appear unrelated on the surface.

Unfamiliar or discipline-specific symbols can distract from the underlying calculus, making problems feel different even when they are not.

To navigate this:

• Translate variables mentally into generic terms like “input” and “output”

• Focus on how the quantities are related, not on the letters used

• Look for the functional form rather than the narrative details

This habit makes structural similarities far easier to recognise.

Units reveal what quantity is changing and with respect to what, acting as built-in indicators of derivative structure.

For example:

• People per year

• Cost per item

• Area per second

Even when the scenario changes, the units retain this structure. Observing the form of the units helps identify parallel mathematical relationships, regardless of context.

Many difficult problems become simpler when you notice they behave like ones you have already solved.

Understanding structural similarity helps you:

• Recognise which differentiation rules to use

• Predict the form of the answer

• Interpret results with confidence

• Avoid being distracted by surface-level differences such as wording or context

This skill is especially valuable in exam settings, where problems may be disguised in unfamiliar narratives.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function P represents the population of a species t years after being introduced into a habitat. At t = 4, the value of P is increasing at a rate of 120 individuals per year.

Explain what the value P'(4) = 120 means in the context of the problem.

Question 1

Maximum 3 marks.

• 1 mark: States that P'(4) represents the instantaneous rate of change of population at t = 4.

• 1 mark: Identifies that the population is increasing at that instant.

• 1 mark: Gives correct units or contextual meaning (e.g., “120 more individuals per year at that moment”).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A company models its total production cost C as a differentiable function of the number of units x produced. The marginal cost function, C'(x), is shown to be increasing for all x greater than 0.

(a) State what marginal cost represents in this context.

(b) Explain how the behaviour of C'(x) indicates a structural similarity to rate-of-change problems in other contexts, such as population growth or geometric change.

(c) At x = 50, the value of C'(50) is 18. Interpret this value in context and describe one real-world implication for the company.

Question 2

Maximum 6 marks.

(a)

• 1 mark: States that marginal cost represents the instantaneous rate of change of total cost with respect to the number of units produced.

• 1 mark: Indicates it describes the additional cost of producing one more unit.

(b)

• 1 mark: Describes that the structure mirrors other rate-of-change settings because it involves a dependent variable changing with respect to an independent variable.

• 1 mark: Recognises that increasing marginal cost indicates a changing rate similar to accelerating population growth or increasing geometric rates.

(c)

• 1 mark: Correctly interprets C'(50) = 18 (e.g., “At a production level of 50 units, the cost is increasing at 18 currency units per additional unit produced”).

• 1 mark: Gives a reasonable real-world implication, such as higher production becoming progressively more expensive or reduced profitability if output increases.