Cultural patterns reflect the distribution and expression of cultural traits, practices, values, and material artifacts across space and time, shaping identity, landscapes, and human interactions.

Sense of Place

Sense of place refers to the emotional, cultural, and symbolic meanings that people associate with particular locations. It emerges from:

Personal memories and lived experiences

Collective traditions and community rituals

Physical features and landmarks unique to a location

Social relationships and cultural significance attached to space

For example, someone who grew up in a small coastal town might associate the smell of salt air and sound of waves with comfort and belonging. This internalized attachment influences how they perceive and value the place.

Importance of Sense of Place

A strong sense of place often contributes to:

Cultural identity: Individuals and communities define who they are based on the places they inhabit and interact with.

Social cohesion: Shared traditions and place-based rituals create bonds among community members.

Mental well-being: Familiar landscapes can foster emotional stability, nostalgia, and happiness.

Place-based activism: People are more likely to engage in environmental protection or urban improvement when they feel emotionally connected to a place.

Variability and Evolution

Sense of place is not static. It changes across time and space depending on:

Life experiences, such as migration or trauma

Age and developmental stage

Cultural exposure, travel, or media influence

Changes in the landscape, such as gentrification or industrialization

Different people can experience the same location in radically different ways depending on their background, identity, and relationships.

Placelessness

Placelessness occurs when locations lose their distinctiveness and appear increasingly uniform, often due to globalization and the spread of mass culture. It is marked by:

Homogeneous architecture, such as identical apartment complexes or shopping malls

The global proliferation of fast food chains and big-box retailers

The replacement of traditional buildings with modern, functional designs

Urban sprawl and standardized transportation networks

Causes of Placelessness

Placelessness is primarily driven by:

Globalization: The spread of ideas, products, and services across borders often promotes standardized forms of culture.

Popular culture: Mass media and consumer trends encourage conformity in fashion, entertainment, and lifestyle.

Economic priorities: Developers may prioritize efficiency and profit over preserving cultural uniqueness.

Cultural Impact

Reduces a community's cultural identity and historical awareness

Weakens individuals' emotional bonds to place

Erodes local traditions and folk architecture

Makes it more difficult for people to differentiate or find meaning in their surroundings

Placelessness challenges the sustainability of cultural diversity and community cohesion.

Environmental Determinism

Environmental determinism is the theory that physical environments—particularly climate and terrain—directly shape human culture, behavior, and societal development. It was prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was popularized by scholars like Ellsworth Huntington.

image courtesy of tandfonline

Examples of environmental determinist thinking:

People in temperate zones are more industrious and productive.

Tropical environments are too hot and humid to support complex societies.

Mountainous terrains limit innovation due to isolation.

Criticisms

Overly simplistic: It neglects political, economic, and cultural influences on development.

Eurocentric and racist: It historically framed non-European cultures as inferior.

Disproved by history: Advanced civilizations have emerged in diverse environments, such as the Inca Empire in the Andes or Mesopotamian civilization in desert regions.

Ignored human agency: It assumes people are passive victims of nature rather than active shapers of their environments.

Environmental determinism has largely been rejected in academic geography but remains an important historical concept to critique and understand.

Possibilism

Possibilism emerged in the early 20th century as a response to environmental determinism. It argues that:

The physical environment limits the range of possible choices available to a culture.

However, humans have agency and use innovation to overcome these limitations.

Culture is shaped more by human decision-making than by nature alone.

Examples of Possibilism

Iceland uses geothermal energy to heat homes despite a harsh climate.

Singapore, a land-scarce island, uses vertical farming and land reclamation to feed its population.

The Netherlands has used dikes and pumps to reclaim land from the sea for centuries.

Importance of Culture and Technology

Possibilism recognizes that culture, tradition, innovation, and social organization play vital roles in how people adapt to and transform their environments. It supports a more nuanced understanding of the human-environment relationship.

Cultural Determinism

Cultural determinism asserts that culture, not the environment, is the primary driver of human behavior, values, and societal organization. This theory holds that:

Cultural beliefs and practices shape how people perceive, use, and organize space.

Humans modify their environments to fit their cultural norms, not the other way around.

Culture defines social roles, moral systems, and technological use.

image courtesy of google images

For example, two societies in similar environments may develop radically different agricultural systems, religions, or family structures based on cultural choices.

Implications

Highlights the role of ideology, religion, and tradition in shaping landscapes.

Emphasizes that diversity in behavior comes from cultural variation, not physical conditions.

Encourages studies of language, religion, rituals, and art to understand human development.

Cultural determinism can help explain the uniqueness of cultural regions and how they persist even in the face of environmental or economic challenges.

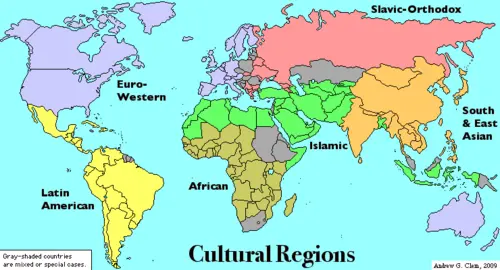

Culture Regions

A culture region is a portion of Earth’s surface where inhabitants share recognizable cultural traits. These traits may include:

Language

Religion

Ethnicity

Architecture

Clothing

Food customs

Types of Culture Regions

Core: The center of cultural traits and practices.

Domain: Area where cultural traits are dominant but not exclusive.

Sphere: The outermost region where traits are still influential but weaker.

Examples:

The Islamic World spans from North Africa to Indonesia, unified by religion but varying in local practices.

The Basque region in Spain and France, where the Euskara language and cultural autonomy define identity.

The Bible Belt in the southern United States, identified by evangelical Protestantism.

Culture regions can be mapped and studied to examine cultural diffusion, integration, and resistance.

Popular and Traditional Culture

Popular Culture

Popular culture is constantly changing, urban, globalized, and consumer-driven. It originates in developed countries and spreads rapidly through media and commerce.

Key characteristics:

Associated with mass production and industrial society

Widely distributed regardless of environment

Often promoted by TV, music, internet, and social media

Changes rapidly with trends and technological shifts

Examples:

American fast food chains like McDonald's found globally

Global fashion trends and music videos

Viral internet challenges and memes

Popular culture can lead to cultural convergence and diminish regional uniqueness.

Traditional (Folk) Culture

Traditional culture is localized, conservative, and deeply tied to place and heritage. It is transmitted from generation to generation and changes slowly over time.

Characteristics:

Associated with rural communities and ethnic groups

Strongly influenced by environment and local resources

Maintained through oral traditions, rituals, and customs

Spread through relocation diffusion, not mass media

Examples:

The Amish in the United States, who reject modern technology

Traditional clothing and festivals among the Maasai in East Africa

Native food preparation and crafts among Quechua-speaking communities

Folk culture is often endangered by modernization and globalization but remains vital for cultural identity and diversity.

Language and Cultural Survival

Language plays a central role in transmitting cultural values, beliefs, and identities. As globalization spreads dominant languages, minority languages face extinction or endangerment.

Endangered and Extinct Languages

Endangered languages have few living speakers and are at risk of dying out (e.g., Yiddish, Ainu, Chamicuro).

Extinct languages are no longer spoken by anyone as a native language (e.g., Latin, Etruscan).

Causes of Language Decline

Colonization and forced assimilation

Economic and educational pressures favoring dominant languages

Urban migration and intermarriage

Media exposure to global languages like English, Spanish, or Mandarin

Cultural Effects

Loss of oral history, ritual knowledge, and worldviews

Weakening of indigenous identity and autonomy

Disappearance of unique perspectives on nature and society

Revitalization Efforts

Governments promoting bilingual education and official language status (e.g., Welsh in Wales).

Community-led efforts to teach language to children and record oral traditions.

Use of social media and apps to teach and spread endangered languages.

Language preservation is key to maintaining cultural diversity and resilience.

Globalization and Cultural Change

Globalization increases interconnectedness across countries and cultures through trade, communication, and migration. It has both positive and negative effects on cultural patterns.

Cultural Convergence

The spread of similar values, norms, and lifestyles across regions

Blending of cultural elements through hybridization

Rise of cosmopolitan identities that transcend borders

Examples:

Global popularity of jeans, smartphones, and fast food

English becoming the lingua franca in business and science

Cross-cultural musical collaborations

Cultural Divergence

Some groups resist global culture to protect their traditions

Emphasis on heritage, religion, or language preservation

Rise of nationalism and cultural revival movements

Examples:

Language laws in Quebec to protect French

Indigenous land rights movements

Traditional dress and ceremonies maintained in rural areas

Globalization is a double-edged sword: it spreads ideas and fosters connection but also threatens local cultures with erasure.

Environmental Impact of Cultural Patterns

Cultural behaviors directly influence how people use and transform their environments.

Resource Use and Pollution

Popular culture promotes high levels of consumption (fossil fuels, water, electricity)

Urbanization and industrial agriculture lead to environmental degradation

Cultural practices may involve land clearing, water diversion, or deforestation

Examples:

Burning fossil fuels for global trade and air travel

Clearing rainforest for cattle grazing due to global meat demand

Overuse of plastic and packaging due to fast fashion and convenience culture

Cultural Preservation and Sustainability

Traditional cultures often promote sustainable practices, such as:

Seasonal agriculture tied to natural cycles

Conservation of sacred groves and water sources

Handcrafted goods made from renewable materials

FAQ

Cultural taboos shape where people choose to live, what resources they use, and how they interact with the environment. These taboos often arise from religious beliefs, social norms, or traditional knowledge systems and create clear boundaries in cultural landscapes. For example:

In Hindu culture, cows are sacred, so beef consumption and cattle slaughter are avoided in many areas of India, influencing land use and dietary practices.

In Islamic cultures, pork is prohibited, affecting livestock farming and food markets.

Some Indigenous groups avoid sacred areas for construction or resource extraction, preserving those spaces.

Taboos reinforce cultural identity and can protect environments but may also restrict economic opportunities depending on local values and external pressures.

Gender influences access to public spaces, patterns of mobility, and division of labor, all of which shape the cultural landscape. In patriarchal societies, women may have limited access to education, work, or political participation, and their spatial roles are often confined to domestic settings. This can be observed in:

Urban areas with limited women’s presence in markets or public transit during certain hours

Rural regions where women manage agricultural tasks while men handle external trade or leadership roles

Restrictions on property ownership for women, affecting land distribution

Conversely, as gender norms shift—especially in more developed societies—women increasingly participate in shaping cities, workplaces, and governance, leading to more equitable and diverse spatial patterns.

Nationalism shapes cultural patterns by promoting a unified identity, language, and set of values that may override local or minority traditions. This can manifest in:

Language policies enforcing the use of a national language in schools, media, and government, such as French in France or Mandarin in China

Emphasis on national holidays, heroes, and myths that bind citizens under a shared historical narrative

Rebranding or erasing place names and monuments that reflect minority or colonial histories

While nationalism can foster unity and pride, it may also suppress cultural diversity, marginalize minority groups, and provoke regional resistance when people feel their heritage is being threatened.

Pilgrimage creates both temporary and long-term cultural patterns by drawing people to sacred sites, fostering interaction, and altering landscapes. These journeys impact space in several ways:

Roads, lodging, and services develop along pilgrimage routes (e.g., Camino de Santiago in Spain or Hajj routes in Saudi Arabia)

Pilgrimage towns often become economic and cultural hubs, maintaining traditions through tourism and religious commerce

Cultural exchange increases as pilgrims from diverse backgrounds share ideas, practices, and goods

Pilgrimages reinforce religious identity and provide a shared experience that strengthens cultural bonds, while also embedding spirituality into the geography of regions and influencing infrastructure and urban form.

Cultural syncretism occurs when different cultural traits merge to form new practices, beliefs, or material culture, especially through contact like trade, conquest, or migration. This process shapes cultural landscapes by:

Creating hybrid religious practices, such as Santería in the Caribbean, blending African and Catholic traditions

Influencing cuisine, language, and dress, like Tex-Mex food or Creole dialects

Producing unique art, music, and architecture that reflect multiple cultural influences (e.g., Moorish architecture in Spain)

Practice Questions

Explain the concept of placelessness and discuss one consequence it has on cultural identity.

Placelessness refers to the loss of unique characteristics in a place due to the spread of popular culture and globalization. This leads to environments where cities and regions begin to look and feel the same, with similar architectural styles, chain stores, and urban layouts. A key consequence of placelessness is the erosion of cultural identity. As local traditions, languages, and architectural styles are replaced by standardized global elements, people may feel disconnected from their heritage and community. This can reduce social cohesion, diminish pride in local culture, and contribute to feelings of alienation and loss of place-based meaning.

Compare and contrast environmental determinism and possibilism in relation to cultural development.

Environmental determinism argues that the physical environment shapes human culture and behavior, limiting societal progress based on geographic and climatic factors. For example, early determinists claimed temperate climates promoted productivity. In contrast, possibilism acknowledges environmental constraints but emphasizes human agency, suggesting that culture is shaped by choices and innovations within those limits. For instance, modern technology allows societies to thrive in deserts or cold regions through irrigation and insulation. While determinism downplays human creativity, possibilism highlights the role of culture, technology, and decision-making in adapting to environmental conditions and shaping diverse cultural landscapes.