Political power and territoriality are foundational concepts in political geography. Political power refers to the capacity of individuals, groups, or governments to influence, control, or determine political outcomes. Territoriality involves the assertion of control over a geographic area, shaping how boundaries are drawn and maintained. Together, these concepts explain how governments organize space, exert authority, and compete for influence.

Understanding Political Power

Political power is expressed in many forms and levels. It can be exerted through legislation, military presence, diplomatic negotiations, or economic influence. Political entities, including states and supranational organizations, use power to:

Control territory

Enforce laws and policies

Protect national interests

Influence other political units

Political power operates at different scales—local, national, regional, and global. The ability of a state to project power depends on its economic resources, military strength, political stability, and alliances. Larger, resource-rich nations often possess greater global influence, while smaller states may have more limited reach but can still wield power through strategic diplomacy or partnerships.

Defining Territoriality

Territoriality is the attempt by an individual or group to influence, affect, or control people, phenomena, and relationships by delimiting and asserting control over a geographic area. It is the spatial expression of political behavior and closely relates to sovereignty and authority. Territoriality in human geography includes:

Establishing recognized borders

Enforcing jurisdiction

Regulating access to land or resources

Asserting national identity through control of space

Physical features (rivers, mountains) and man-made markers (walls, fences, signs) often symbolize territorial claims. States use territoriality to legitimize authority and consolidate control. This principle is evident in the use of flags, national anthems, military outposts, and mapping to reinforce sovereignty.

The Role of Geopolitics

Geopolitics is the study of how geographic factors influence political decision-making, international relations, and strategic behavior. It involves the examination of spatial structures, power dynamics, and territorial disputes. Governments and political scientists use geopolitical theories to:

Interpret foreign policy decisions

Predict patterns of conflict or cooperation

Assess strategic advantages of location

Geopolitics considers variables such as access to oceans, proximity to rivals, availability of resources, and location along trade routes. Nations seek geographic advantage to strengthen security, influence trade, and dominate key regions.

Organic Theory

Developed by German geographer Friedrich Ratzel in the late 19th century, the Organic Theory suggests that states function like living organisms. To survive, they must grow and consume territory. Key features include:

A state's vitality depends on territorial expansion

Weak states are absorbed by stronger, expanding ones

Growth is essential to national survival

Ratzel believed that a state requires "Lebensraum" or living space, to accommodate its population and economic development. This theory influenced imperialist ideologies, including Nazi Germany's expansion into Eastern Europe. Critics argue that it is overly deterministic and disregards moral and legal constraints on conquest.

Who Was Friedrich Ratzel?

Friedrich Ratzel was a German geographer and ethnographer who lived from 1844 to 1904. Trained in biology and influenced by Darwin's theory of evolution, he applied biological concepts to political geography. In his work "Political Geography" (1897), Ratzel proposed that the growth of a state was analogous to a biological organism needing space, resources, and favorable conditions to thrive. He introduced the concept of Lebensraum, which emphasized territorial expansion as essential for state survival. His theories laid the foundation for geopolitical thinking, but also raised ethical concerns due to their use in justifying aggressive imperialism.

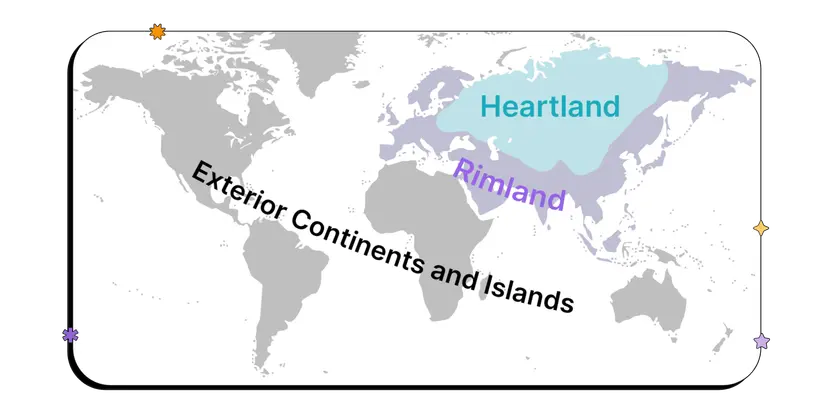

Heartland Theory

British geographer Halford Mackinder introduced the Heartland Theory in 1904. He argued that the central landmass of Eurasia—stretching from Eastern Europe to Siberia—was the "pivot area" or heartland. Key ideas of the Heartland Theory include:

Control of Eastern Europe leads to control of the Heartland

Control of the Heartland enables control over the World Island (Eurasia and Africa)

Control of the World Island results in world dominance

Mackinder believed that land-based power was more important than sea power, especially with the expansion of railways and infrastructure in the heartland. His theory influenced Western fears about Soviet expansion during the Cold War. Critics point out that the theory underestimates maritime power and the complexity of global politics.

Who Was Halford Mackinder?

Halford Mackinder (1861–1947) was a British scholar who helped establish geography as an academic discipline. He viewed geography as central to understanding global power relations. In his pivotal work, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” he described the Heartland as the key to global control, suggesting that whoever controlled this area would dominate global politics. His ideas were foundational during the 20th century, influencing strategic military planning, particularly NATO policies aimed at containing Soviet influence. Despite criticism for its Eurocentric and deterministic approach, the Heartland Theory remains a cornerstone of geopolitical analysis.

Rimland Theory

Nicholas Spykman introduced the Rimland Theory in response to Mackinder’s Heartland focus. Spykman argued that coastal fringes, not the interior, were most vital to global power. The Rimland Theory asserts:

The rimland includes Europe’s coast, the Middle East, and Asia’s coastal zones

Control of the rimland ensures access to sea routes and trade

The rimland connects populous, economically developed, and politically active regions

Spykman believed that sea power and naval supremacy were crucial to controlling the global economy and maintaining security. His work influenced U.S. Cold War policy, which emphasized containment of Soviet power along Eurasia’s periphery.

Who Was Nicholas Spykman?

Nicholas Spykman (1893–1943) was a Dutch-American political scientist and strategist. He is known for coining the term "Rimland" and authoring "The Geography of the Peace" in 1944. Spykman disagreed with Mackinder’s emphasis on the Heartland, proposing instead that power lies in the control of the coastal zones that surround it. These areas are more economically and politically dynamic, with key shipping lanes, ports, and international commerce. His theory supported naval expansion and became a basis for U.S. efforts to form military alliances and build bases along the Eurasian rim.

Comparing the Three Theories

Each theory offers a different geographic lens on political power and territorial control:

Organic Theory focuses on natural expansion for survival.

Heartland Theory emphasizes land-based dominance of Eurasia.

Rimland Theory prioritizes control over coastal and maritime regions.

These theories were used to justify imperialism, colonialism, and military expansion. They continue to influence modern geopolitical strategies, especially in discussions of NATO, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and Russian-Western tensions.

The Symbolism and Practice of Territoriality

Territoriality goes beyond physical occupation of land. It includes the symbols, laws, and practices states use to assert ownership. Forms of territorial expression include:

National flags flown at borders

Military patrols and checkpoints

Government-issued maps

Diplomatic recognition of borders

In some cases, disputed territories challenge political power and national sovereignty. Examples include:

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict over the West Bank and Gaza

The India-China border dispute in the Himalayas

Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014

Such disputes often involve complex historical claims, cultural affiliations, and geopolitical calculations. Political power is reinforced or contested through negotiations, war, treaties, or international mediation.

The Complexity of Defining Territory

Drawing borders is not always a straightforward process. Disagreements may arise over:

Ethnic identity: Different ethnic groups may claim the same area based on cultural or historical ties.

Natural resources: Disputes over oil, gas, water, or minerals can fuel territorial claims.

Historical claims: States may claim land based on past occupation or governance, even centuries ago.

Colonial boundaries: Many post-colonial states inherited borders drawn by European powers, often ignoring local demographics or tribal lines.

Some regions remain partially or wholly unrecognized by the international community. For instance:

Taiwan claims independence from China, but is recognized by few countries.

Kosovo is recognized by many but not all nations, including Serbia.

Western Sahara is claimed by both Morocco and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

These unresolved disputes reflect the tension between territoriality and legitimacy, identity, and recognition on the world stage.

FAQ

Territorial sovereignty and territorial integrity are related but distinct concepts crucial to understanding how states function and defend their power.

Territorial sovereignty refers to a state’s legal right to govern its land and people without external interference. It means the state has the final say over political, economic, and social matters within its borders.

Territorial integrity, however, is the principle that a state's borders should not be violated or altered by outside forces. It emphasizes the protection of a state's physical boundaries from foreign aggression or influence.

These concepts matter because violations often lead to international conflict. For example, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was seen as a breach of Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sparked global condemnation. While Russia claimed sovereignty over the region, much of the world recognized it as a violation of Ukraine's legitimate rights. These principles are foundational to global diplomacy, the United Nations Charter, and international law.

Supranational organizations can significantly alter how states express and maintain territoriality by encouraging shared sovereignty and cooperation beyond national borders.

Supranational bodies like the European Union require member states to adhere to common regulations, sometimes limiting their independent decision-making over economic, legal, and border policies.

This integration can blur traditional notions of sovereignty, as seen in the Schengen Area where border checks between participating countries are eliminated, making the concept of territorial control less rigid.

States gain benefits like economic growth, political influence, and collective security but may lose some autonomous control over internal and external policies.

For example, when the EU accepts new members, those countries must adopt EU laws, which may shift how they control their territory or interact with neighbors. While this promotes regional unity, it can also provoke nationalist backlash from citizens or political groups who feel sovereignty is being compromised. The Brexit vote illustrates how tension over supranational influence can lead a state to reassert its territorial independence.

Buffer zones are areas created or maintained between potentially hostile states or regions to reduce direct confrontation. They reflect a deliberate geopolitical strategy tied to controlling space and projecting influence.

Buffer zones serve as security barriers, offering protection by placing a neutral or friendly territory between rivals.

They also signal power and influence, allowing a dominant state to shape the politics of a neighboring area without full annexation.

Examples include the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea, or historically, the Soviet Union’s satellite states in Eastern Europe during the Cold War. These zones were not merely geographic areas—they were instruments of control. The buffer zone strategy shows how states use territoriality to build protective perimeters and limit rival influence without direct conflict. It’s a form of passive aggression, asserting dominance while avoiding open war.

Indigenous land claims challenge traditional state-based territoriality by asserting historical and cultural rights over land that predates current political borders.

Indigenous groups often argue for sovereignty based on ancestral occupation, long-standing cultural practices, and legal agreements such as treaties.

These claims may conflict with national governments, especially when natural resources or strategic interests are involved.

For example, in the United States, Native American tribes have established sovereign territories where they exercise limited self-governance, such as managing their own laws and businesses. In Canada, land acknowledgments and treaty negotiations have grown in importance as the government recognizes indigenous political power. These movements highlight that territoriality is not just about geography—it also encompasses cultural, historical, and legal dimensions. Political power here is expressed through court cases, protests, and negotiations, revealing the ongoing contest between indigenous autonomy and national control.

Symbolic expressions of territoriality, such as flags, national anthems, monuments, and maps, play a vital role in reinforcing state authority and shaping collective identity.

Symbols project state legitimacy, reminding both citizens and outsiders of who controls the land.

These expressions help unify populations, strengthen national pride, and legitimize the state’s presence in contested or diverse regions.

For example, raising a national flag in disputed areas like Kashmir or the South China Sea reinforces a claim of sovereignty. Naming streets after national heroes, building war memorials, or celebrating independence days are subtle ways of embedding political power into everyday life. Maps that omit contested territories or display disputed borders differently are also political tools. These symbolic acts show how states use emotional and cultural means to support territorial claims and maintain control, even without physical enforcement. Symbolic territoriality becomes especially important in areas with ethnic minorities, where the state may seek to assert dominance through cultural integration.

Practice Questions

Explain how geopolitical theories such as the Heartland and Rimland theories help understand historical or contemporary power struggles between states. Provide one example for each.

The Heartland and Rimland theories offer frameworks for interpreting state strategies. The Heartland Theory, proposed by Mackinder, argued that control of Eastern Europe and Central Asia provides global dominance. This logic influenced Cold War policies and Russia’s interest in Ukraine. The Rimland Theory by Spykman emphasized control of coastal zones, shaping U.S. containment strategies like stationing forces in South Korea and Japan. Together, these theories illustrate how geography influences military and political power, guiding foreign policy and explaining conflicts like NATO’s expansion or China’s Belt and Road Initiative targeting both interior and coastal regions for influence.

Describe how the concept of territoriality explains the actions of a state asserting power within or beyond its borders. Use examples to support your response.

Territoriality refers to the control and influence a state exerts over a defined area. It helps explain why states enforce borders, build walls, or intervene abroad. For example, China’s actions in the South China Sea reflect territoriality—building artificial islands to assert sovereignty and control trade routes. Internally, the U.S. asserts territoriality by regulating immigration at its southern border. Both actions show how states use territoriality to solidify sovereignty, project power, and protect national interests. Through physical control and symbolic claims, territoriality shapes foreign policy, regional dominance, and conflict resolution efforts, making it central to understanding modern political geography.