Political boundaries are essential elements in the organization of space, providing structure to global and local political systems. These boundaries serve multiple functions that shape how territories are governed, how people interact, and how resources are distributed and controlled. Understanding the functional role of political boundaries is key to understanding how human geography operates at the local, national, and international scales.

The Role and Purpose of Political Boundaries

Political boundaries serve as the limits of sovereign power and determine where a state or governing body has legal authority. These boundaries separate areas of different legal jurisdictions and help maintain order within and between political entities. In addition to defining the territorial extent of a state’s control, political boundaries regulate how people, goods, and ideas move across spaces. Boundaries can be physical, legal, administrative, symbolic, or economic, and they can range in scale from international borders between countries to private property lines between individuals.

Key functions of political boundaries include:

Maintaining sovereignty and governance over clearly defined territories.

Establishing jurisdiction for enforcing laws and regulations.

Controlling the flow of migration, trade, and communication between places.

Allocating access to and control over natural resources, both on land and at sea.

Reducing or igniting conflict depending on clarity, enforcement, and agreement.

Shaping identity, culture, and national unity.

Types of Boundary Disputes and Their Functions

Because political boundaries serve so many purposes, they are also sources of conflict. Disputes over boundaries often occur when states or other groups disagree on the exact location, control, or use of a border.

Definitional Disputes

Definitional disputes occur when there is confusion or disagreement over the wording of legal documents that define a boundary. These disputes usually stem from historical treaties or vague geographical descriptions.

Example: The boundary between Chile and Argentina has long been subject to definitional disputes. The Andes Mountains were meant to serve as the border, but the southern region is sparsely populated and topographically complex. Disagreement arises over the interpretation of where the mountain crest lies, leading to competing claims.

Definitional disputes often require legal clarification, reinterpretation of treaty language, or international arbitration to resolve.

Locational Disputes

Locational disputes arise when two parties agree on the definition of the boundary but disagree on its actual placement on the ground.

Example: The post-World War I boundary between Germany and Poland led to a locational dispute. Although a boundary was defined in the Treaty of Versailles, it placed ethnic Germans within Polish territory. This resulted in German claims that the territory rightfully belonged to Germany and justified future actions under the Nazi regime.

These disputes are often fueled by:

Ethnic enclaves or populations living across national borders.

Inaccurate maps or geographic knowledge at the time of boundary creation.

Shifting physical landscapes (e.g., river movement or erosion).

Operational Disputes

Operational disputes involve disagreements over how a boundary should function or be administered. These disputes may not question the boundary’s location but focus on how it is managed.

Example: During the Syrian civil war, millions of refugees crossed borders into Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey. These countries disagreed on who should accept the refugees and under what conditions. The dispute revolved around the operational role of the boundary—should it be tightly controlled or open for humanitarian purposes?

Other examples of operational disputes include disagreements over customs enforcement, security, visa regulations, and the construction of border infrastructure like walls and checkpoints.

Allocational Disputes

Allocational disputes arise when political boundaries intersect natural resources, such as oil fields, water supplies, or mineral deposits. The placement of a boundary affects which state has access to and can exploit these resources.

Example: In 1990, Iraq accused Kuwait of slant drilling into its oil reserves beneath the border. Iraq’s response was to invade Kuwait, sparking the Gulf War. This allocational dispute centered on the interpretation of underground resource boundaries.

Allocational disputes are especially common in regions with overlapping resource-rich zones, such as rivers, underground aquifers, or offshore oil fields.

Territorial Disputes

Territorial disputes refer to conflicts over the actual ownership of a particular region. These disputes occur when states claim control over the same territory, usually based on history, ethnicity, or strategic interest.

Example: The dispute over the Kashmir region between India and Pakistan remains one of the most contentious in the world. Both countries claim full sovereignty over the area and have engaged in multiple wars over it.

Territorial disputes can have serious consequences and are often deeply rooted in national identity, colonial legacies, and geopolitical strategy.

Irredentism and Its Relationship to Boundaries

Irredentism is the belief that a country has a right to reclaim territory that it sees as part of its historical or cultural identity. This often arises when ethnic or cultural groups are split across political boundaries.

Example: Nazi Germany annexed Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia under the pretext that ethnic Germans lived there. This expansionist policy was rooted in the idea that boundaries should reflect cultural unity, not just legal or geographic distinctions.

Irredentist movements often challenge the stability of boundaries by asserting that current lines are illegitimate or unnatural. They can lead to military conflict or long-term diplomatic tension.

Maritime Boundaries and the Law of the Sea

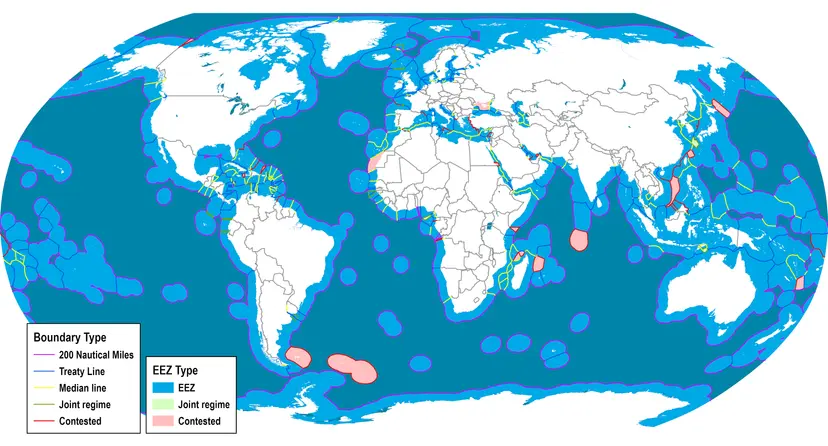

Political boundaries extend beyond land into oceans and seas. These maritime boundaries are defined under international law, primarily by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982.

UNCLOS divides maritime space into several zones:

Territorial Sea (0–12 nautical miles): Coastal states have full sovereignty, including control over airspace and seabed.

Contiguous Zone (12–24 nautical miles): States can enforce customs, immigration, and sanitation laws but do not have full sovereignty.

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ, up to 200 nautical miles): States can exploit marine resources, including fishing, oil, and gas, but must allow free navigation.

High Seas: Areas beyond any national jurisdiction. Open to all states for fishing, navigation, and scientific research.

Source: Transport Geography

Maritime Boundary Disputes

Disputes over maritime boundaries often emerge when EEZs overlap or when new resource deposits are discovered.

Example: The South China Sea is a hotbed of maritime boundary disputes. China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and others claim overlapping zones, particularly due to the presence of valuable oil and gas resources and strategic shipping lanes.

Another example: The Arctic Ocean is increasingly contested as melting ice opens up new shipping routes and access to untapped resources. Countries like Russia, Canada, and Denmark are asserting overlapping claims.

These disputes highlight the functional importance of political boundaries in maritime resource control, environmental protection, and naval strategy.

Internal Boundaries and Their Functional Roles

Not all political boundaries lie between countries. Internal boundaries, such as those between states, provinces, or administrative districts, also serve essential governance functions.

Subnational Boundaries

Example: In the United States, each state operates under a federal system where states have their own laws, governments, and jurisdiction over education, healthcare, and taxation.

Example: In India, states are formed largely along linguistic lines, reflecting the functional need for governance in culturally distinct regions.

These boundaries affect how services are delivered, how political power is distributed, and how regional identities are maintained. They also influence elections, as electoral boundaries determine representation in legislative bodies.

Indigenous Land Boundaries

In many countries, indigenous land claims and territories are defined within or across state borders. These areas may have limited autonomy or special legal status.

Example: In Canada, many First Nations operate under treaties that define land rights, self-governance, and resource use. These internal boundaries reflect a blend of historical claims and modern governance.

However, disputes often arise between governments and indigenous groups over land development, environmental protection, and sovereignty.

Private Property Boundaries

At the smallest scale, political boundaries include private property lines, which are legal boundaries that define ownership and usage rights.

These boundaries are often marked by fences, hedges, or survey lines.

Disputes between neighbors over unclear property lines can result in court cases or land surveys to determine rightful ownership.

While less dramatic than international borders, these boundaries are essential to legal property rights, urban planning, and land use.

Security and the Enforcement of Political Boundaries

Political boundaries are often secured through a combination of physical infrastructure, technology, and legal frameworks.

Militarized Boundaries

Example: The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is one of the most heavily guarded borders in the world, separating North and South Korea. It serves both as a physical and symbolic boundary between opposing political ideologies.

Border Control and Surveillance

Modern states invest heavily in technology to manage and monitor their boundaries:

Use of drones, surveillance towers, and biometric scanners.

Smart border fences that detect motion, heat, or vibrations.

Satellite imagery to monitor unauthorized crossings or environmental changes.

These tools are used not only to prevent illegal immigration but also to detect smuggling, trafficking, and environmental violations.

How Boundaries Shape Sovereignty and State Power

The most important function of political boundaries is to define and protect state sovereignty—the ability of a state to govern itself independently.

Boundaries define who is a citizen, what laws apply, and who has the right to enforce them.

Sovereign boundaries are recognized by international organizations such as the United Nations.

When a boundary is disputed or ignored, a state's sovereignty is weakened, which can lead to internal unrest or international conflict.

Summary of Key Concepts

Definitional Dispute: Legal ambiguity over boundary language.

Locational Dispute: Disagreement on physical boundary placement.

Operational Dispute: Conflict over boundary management and enforcement.

Allocational Dispute: Competition over shared resources.

Irredentism: Claiming land based on shared culture or history.

UNCLOS: International law defining maritime zones.

EEZ: Exclusive access to marine resources up to 200 nautical miles.

High Seas: Global commons beyond state control.

FAQ

Political boundaries can significantly affect a country's access to key strategic locations such as canals, straits, and port cities. These chokepoints are narrow passages that are critical for global trade and military movement. Countries that control boundaries near chokepoints often gain economic and geopolitical advantages.

Examples of chokepoints include the Strait of Hormuz, Panama Canal, and Suez Canal.

Control of such areas allows states to regulate the passage of oil, goods, and military vessels.

Political boundaries near these regions can lead to diplomatic disputes or military tension.

Even minor border shifts or disputes can affect global shipping costs and trade security.

States may build military bases or infrastructure to reinforce their presence near strategic chokepoints.

Because of their global significance, boundaries near these zones are often reinforced, heavily patrolled, and diplomatically sensitive.

Enclaves and exclaves are geographical anomalies created by boundaries and can complicate governance, access, and diplomacy.

An enclave is a territory completely surrounded by another country. An exclave is a territory that is politically attached to a larger state but not physically contiguous with it.

Example of an enclave: Lesotho is a sovereign country entirely surrounded by South Africa.

Example of an exclave: Kaliningrad is a Russian exclave bordered by Poland and Lithuania, separate from the main territory.

These create logistical challenges for the movement of goods, military, and services.

Exclaves may require agreements with neighboring states for transportation or utility access.

Enclaves can develop cultural and political distinctions due to their isolation.

Boundary disputes may arise over access rights, resource distribution, or citizenship issues.

These cases reveal how boundaries can lead to fragmented sovereignty and complex political negotiations.

Boundaries can complicate environmental management by dividing ecosystems, water sources, or wildlife migration routes between two or more jurisdictions.

Transboundary rivers, forests, and air basins often require cooperative management agreements.

Differences in national environmental regulations can lead to uneven pollution control, overuse of shared resources, or habitat destruction.

Example: The Amazon Rainforest spans several South American countries, requiring multinational cooperation to address deforestation.

Example: The Mekong River passes through China, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, necessitating water-sharing agreements and ecological coordination.

Disputes can arise when upstream countries alter water flow or build dams without consulting downstream nations.

Boundaries can also slow disaster response efforts when wildfires or oil spills cross into neighboring territories.

Environmental concerns highlight the need for cross-border agreements that transcend political boundaries for sustainable resource use.

Supranational organizations like the European Union, African Union, or ASEAN can reshape how boundaries function by reducing their political and economic impact.

They often ease or eliminate restrictions on the movement of goods, people, and services across member states.

Example: In the European Union’s Schengen Area, internal borders are largely open, allowing passport-free travel.

These organizations may set common legal standards, aligning immigration policies, trade laws, or environmental regulations across borders.

They promote shared sovereignty, where national governments relinquish some control for broader regional goals.

In conflict zones, such organizations can act as mediators or peacekeepers, reinforcing or monitoring disputed boundaries.

They can also fund cross-border infrastructure, trade corridors, or environmental initiatives.

Supranational organizations reduce the rigid functionality of traditional boundaries and promote integration across state lines.

Accurate census-taking is heavily dependent on clearly defined and well-enforced political boundaries. These lines determine how population data is organized and interpreted.

Census regions often align with political boundaries such as municipalities, districts, or states.

Changes or disputes in boundaries can lead to overlapping claims, undercounting, or exclusion of certain populations.

Political boundaries help allocate government funding, representation, and services, making accurate data collection essential.

In contested areas, residents may avoid census participation due to fears of surveillance, deportation, or political retribution.

Example: In border regions like Kashmir or the Gaza Strip, political instability affects the reliability of demographic statistics.

Boundary delineation affects how ethnic groups, economic disparities, and migration patterns are recorded and interpreted.

Practice Questions

Explain how the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines maritime boundaries and discuss one way in which these boundaries can lead to international disputes.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishes maritime zones such as the Territorial Sea (up to 12 nautical miles), Contiguous Zone (12–24 nautical miles), and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ, up to 200 nautical miles). These zones grant states rights to control navigation, enforce laws, and exploit marine resources. Disputes often arise when EEZs overlap or when countries contest ownership of resource-rich areas. For example, in the South China Sea, several nations claim overlapping EEZs, leading to tensions over fishing rights, oil exploration, and freedom of navigation in contested waters.

Describe the difference between operational and allocational boundary disputes and provide an example of each.

Operational boundary disputes involve disagreements about how a boundary should function, such as rules governing immigration or customs. For instance, during the Syrian refugee crisis, neighboring countries disagreed on how to manage border crossings and the responsibilities of accepting refugees. Allocational disputes, on the other hand, occur when boundaries divide valuable resources, leading to conflict over ownership or usage rights. An example is the Iraq-Kuwait conflict in 1990, where Iraq accused Kuwait of drilling into its oil reserves, triggering a war. These disputes illustrate how boundaries not only separate territories but also regulate access and control over vital resources.