Internal boundaries divide a larger political or organizational entity into smaller units, shaping governance, representation, and access to resources within a country or institution.

What Are Internal Boundaries?

Internal boundaries are subdivisions within a sovereign state or organization that separate regions, districts, or jurisdictions from one another. Unlike international borders, which divide separate nations, internal boundaries operate entirely within the same country or governing structure. These boundaries help organize space for purposes such as administration, law enforcement, electoral representation, resource management, and service delivery.

Internal boundaries are found at multiple scales, including:

National divisions like states, provinces, or territories.

Subnational divisions like counties, municipalities, or school districts.

Urban divisions such as neighborhoods, boroughs, or city council districts.

Organizational boundaries separating departments, zones, or sectors.

These lines often appear on political or administrative maps and can shape how resources, power, and responsibilities are distributed across a population.

How Are Internal Boundaries Created?

The creation of internal boundaries is influenced by multiple factors—political decisions, historical events, cultural differences, geographic features, and organizational needs.

Political Decisions

Governments often draw internal boundaries to better manage regions or provide representation.

Legislatures create boundaries for electoral districts, municipalities, and administrative zones.

Redistricting occurs after censuses to ensure equal representation by adjusting voting districts based on population changes.

New divisions may be introduced for decentralization, conflict resolution, or urban development.

These boundaries often require approval from elected officials, referenda, or constitutional amendments, depending on the country’s governance model.

Historical and Cultural Influences

Internal boundaries can reflect historical territories, colonial legacies, or cultural divides.

Example: India's linguistic states were formed in the 1950s to preserve regional language groups, aligning internal boundaries with cultural identities.

Example: Belgium is divided into regions and communities based on language (Dutch, French, and German), helping to reduce ethnic tension.

These boundaries aim to balance cultural preservation with national unity, although they may also reinforce identity-based politics or separatist movements.

Physical Geography

Geographic features like mountains, rivers, coastlines, and deserts often influence internal boundary placement.

Rivers may act as natural divides between municipalities or counties.

Mountain ranges can create logical boundaries due to difficulty of access.

Urban planning uses roads, railways, and natural features to define zoning lines.

Physical geography helps create boundaries that are clear, recognizable, and efficient, though it may not align with population or community structures.

Organizational Needs

Internal boundaries within companies, schools, or service sectors are created to manage operations effectively.

Departments in a business (HR, Finance, Sales) represent internal boundaries of responsibility.

School districts assign students to local schools, affecting educational access and funding.

Emergency zones help coordinate disaster response and public services like policing or firefighting.

These boundaries are often based on workload distribution, geographic proximity, or demographic need.

Examples of Internal Boundaries

State and Provincial Borders

In federal systems like the United States, Canada, or Australia, states or provinces have defined borders that grant them certain powers under national law.

Each U.S. state has its own legislature, judicial system, and governor.

Canadian provinces manage education, healthcare, and language policy.

These boundaries impact taxation, lawmaking, infrastructure, and cultural autonomy.

Voting Districts

Electoral districts determine how populations are represented in legislatures.

Each U.S. congressional district elects one member to the House of Representatives.

Local councils, state assemblies, and school boards all rely on internal boundaries to allocate seats.

The goal is to ensure equal representation, although this system can be manipulated through gerrymandering.

Urban Neighborhoods and Boroughs

Cities are divided into zones or neighborhoods that carry distinct identities and often influence local government services, planning, and investment.

Example: New York City includes five boroughs, each with unique administrative functions.

Neighborhood boundaries affect policing, zoning, infrastructure, and resource distribution.

In many cities, historical redlining and housing policies have led to long-term socio-economic boundaries that persist today.

Indigenous and Tribal Territories

In countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia, internal boundaries exist between indigenous nations and the state.

Native reservations often have limited self-governance under federal law.

These internal boundaries define jurisdiction, land rights, and resource management.

They reflect centuries of political negotiation, legal recognition, and cultural preservation, though they are often contested and challenged.

Organizational Structures

Internal boundaries in workplaces or institutions structure how tasks and responsibilities are divided.

A hospital may have departments for surgery, emergency care, pediatrics, etc.

A university has faculties or colleges like Arts and Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

These boundaries allow specialization, efficiency, and coordinated decision-making.

Redistricting and the Role of the Census

What Is Redistricting?

Redistricting is the process of redrawing the boundaries of electoral districts to reflect population changes.

In the U.S., it happens every ten years after the census.

It ensures that each district contains roughly the same number of people, maintaining equal representation under the principle of “one person, one vote.”

Redistricting affects congressional, state legislative, and local council districts.

Because of its influence on electoral outcomes, redistricting is highly political and often controversial.

The Census and Why It Matters

The census is a national survey conducted every decade in the U.S. and in many other countries.

It counts people and collects data on age, race, income, housing, and more.

This data determines representation, federal funding, and community services.

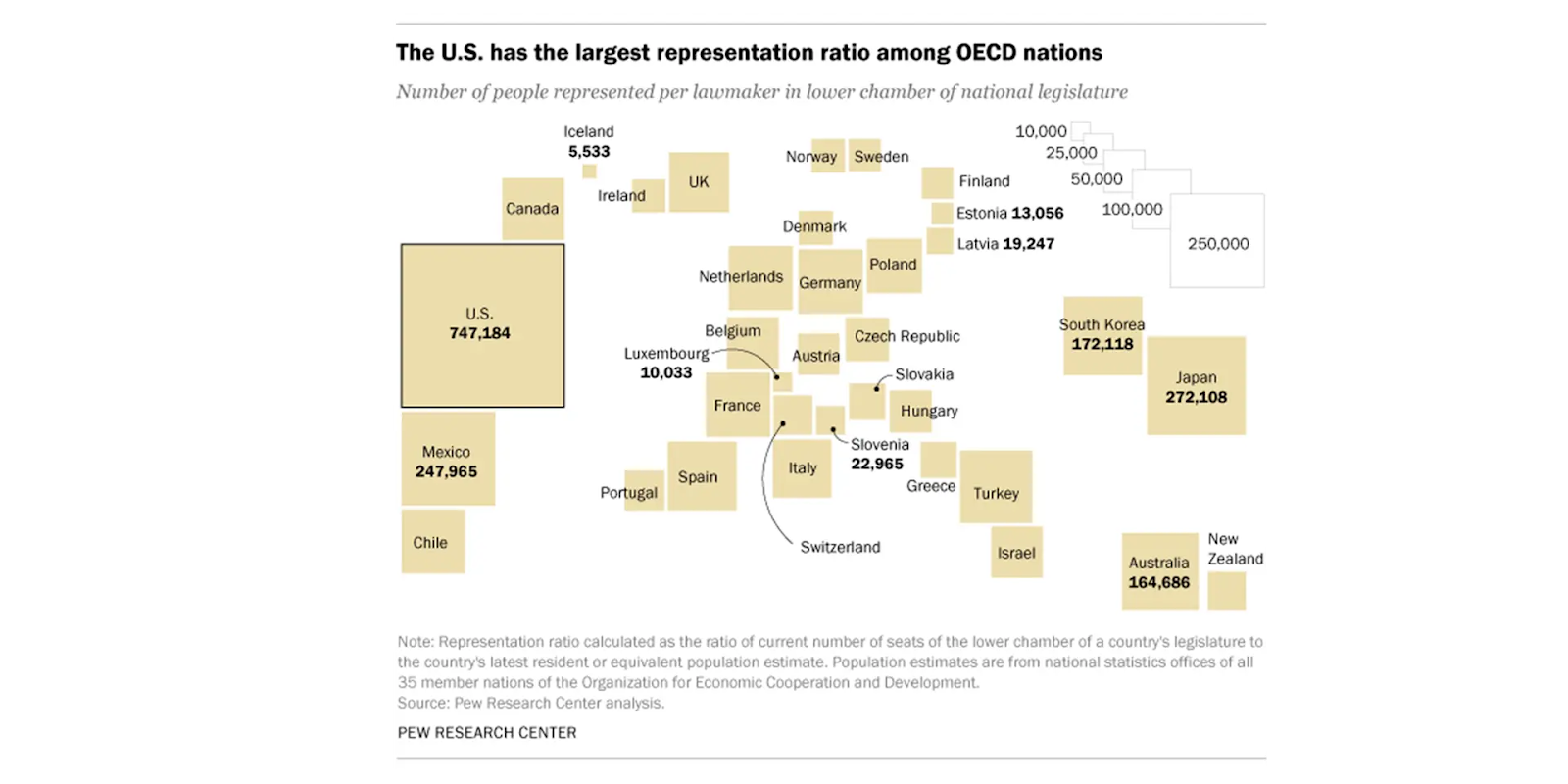

In the U.S., each of the 435 congressional seats must represent a similar number of people. After the census:

States may gain or lose seats in Congress (called reapportionment).

District lines are redrawn based on new population data.

Source: Pew Research Center

For example, if one district has 800,000 people and another only 600,000, the larger one may be split or altered to balance population sizes.

Gerrymandering and the Abuse of Redistricting

What Is Gerrymandering?

Gerrymandering is the deliberate manipulation of district boundaries to favor one political party or group.

The term originates from a district drawn in Massachusetts in 1812, which was said to resemble a salamander.

It results in unfair advantages, suppressing the influence of certain voters and creating noncompetitive elections.

How Gerrymandering Works

Boundaries are manipulated to cluster or divide voting groups based on race, income, or political affiliation.

As a result, one party may win more seats without winning more votes overall.

This is done through various techniques:

Cracking

Dividing a concentrated group (often a minority or political opposition) across several districts so they can't form a majority in any.

Example: Spreading liberal voters across conservative-leaning districts so their influence is minimized.

Packing

Placing many of one group’s voters into a single district so that surrounding districts are more competitive or favor the dominant party.

This often results in the group winning one seat overwhelmingly while losing multiple others narrowly.

Stacking

Combining low-turnout or minority groups with high-turnout majority groups, so the former has little impact on outcomes.

This dilutes the electoral strength of certain communities, even if they are numerically significant.

Hijacking

Redrawing boundaries so that two incumbents from the same party must run against each other, eliminating one.

Kidnapping

Moving an elected representative's residence into a different district where their chances of winning are lower.

These tactics all aim to weaken electoral competition and cement political control, often undermining democratic representation.

The Impact of Internal Boundaries

Internal boundaries affect a wide range of social, political, and economic outcomes:

Political Representation

The way districts are drawn influences who gets elected and which communities have a voice.

Minority groups may be underrepresented or overrepresented depending on boundary design.

Boundary manipulation can result in policy outcomes that don't reflect public preferences.

Access to Resources

School district boundaries can create disparities in education quality.

Healthcare, public transport, and police funding may be uneven due to district borders.

Some areas may receive more federal or state funding based on how they are counted and represented.

Cultural and Community Identity

Boundaries can divide or unify communities based on language, religion, or ethnicity.

Well-drawn internal boundaries may preserve cultural heritage and promote civic participation.

Poorly drawn or manipulated boundaries may erode trust and deepen inequality.

Legal and Administrative Jurisdiction

Internal boundaries define where laws apply and which agency enforces them.

Zoning regulations, taxation, and public works projects are all governed based on internal divisions.

From police precincts to public libraries, boundaries determine how citizens experience governance and services.

Summary of Key Terms

Internal Boundary: A division within a state or organization used to manage space, governance, or operations.

Redistricting: The process of adjusting voting districts to reflect population changes.

Census: A national count and survey of the population used for resource allocation and representation.

Gerrymandering: Manipulating internal boundaries to favor one group or party.

Cracking: Splitting a group across districts to weaken its voting power.

Packing: Concentrating a group into one district to reduce its impact elsewhere.

Stacking: Combining different voter groups to dilute one’s effectiveness.

Hijacking: Drawing lines to force politicians from the same party into competition.

Kidnapping: Moving a representative’s home into an unfamiliar or hostile district.

FAQ

Internal boundaries significantly impact the allocation and accessibility of public services within a state. These boundaries often determine which schools children attend, what healthcare facilities are available, and where public transportation routes operate. When boundaries are drawn based on socio-economic or political interests rather than population needs, disparities can arise.

Wealthier districts often receive better-funded schools due to higher property tax revenue.

Healthcare facilities may be concentrated in certain districts, leaving others underserved.

Transportation infrastructure is more developed in urban districts than in remote or rural areas.

Internal boundaries can reinforce patterns of inequality if not regularly reviewed and equitably managed.

Thus, boundaries shape how equitably resources are distributed, affecting quality of life across regions.

Independent redistricting commissions are designed to take the power of redrawing internal political boundaries out of the hands of partisan legislators. These commissions aim to create fairer, more representative districts based on population data rather than political advantage.

Composed of nonpartisan members or balanced party representation.

Use criteria such as geographic compactness, community integrity, and equal population.

Aim to reduce gerrymandering and restore public trust in the electoral process.

Increasingly adopted at the state level in the U.S. (e.g., California, Arizona).

Their effectiveness depends on transparency, legal authority, and public input. These commissions demonstrate how internal boundaries can be managed more democratically.

Internal boundaries can either protect or marginalize ethnic and cultural minorities, depending on how they are drawn and governed. If boundaries respect the distribution of cultural groups, they can promote inclusion and self-governance. If not, they can dilute political power and disrupt community cohesion.

Boundaries that divide minority populations across multiple districts (cracking) weaken their voting power.

Concentrating minorities into one district (packing) may limit their influence beyond that area.

In multicultural states, special boundaries may be drawn to create autonomous regions (e.g., Nunavut for Inuit people in Canada).

Poorly drawn boundaries can lead to systemic underrepresentation and cultural marginalization.

The design and purpose of internal boundaries thus play a crucial role in minority rights and representation.

Yes, internal boundaries can influence economic development by determining which regions receive investment, infrastructure, and services. Political boundaries often dictate where economic zones are created, which districts get prioritized in budgets, and how resources are shared.

Districts with stronger political representation may secure more funding and projects.

Urban-rural divides are often reinforced by administrative boundaries, leading to uneven development.

Boundaries can affect tax revenue distribution, leading to imbalances in service provision.

Redrawing boundaries to include commercial or affluent zones may boost a district’s economic standing.

Strategically drawn internal boundaries can stimulate development, but manipulative boundaries can entrench economic disparity.

Communities of interest refer to populations that share common social, cultural, economic, or geographic characteristics and therefore benefit from being grouped within the same political boundary. When district lines are drawn to keep such communities intact, their needs are more likely to be represented effectively.

Include neighborhoods with shared language, religion, ethnicity, or industry.

Protecting communities of interest can prevent political marginalization.

Helps legislators focus on specific regional concerns with greater accountability.

Ignoring these communities may result in diluted representation and less targeted policymaking.

Recognizing and preserving communities of interest is considered a best practice in ethical and inclusive redistricting.

Practice Questions

Explain how internal political boundaries, such as voting districts, influence political representation in a federal state. Provide an example to support your explanation.

Internal political boundaries like voting districts are essential for determining representation in legislatures. These boundaries are drawn to ensure that each district contains a roughly equal population, preserving the principle of “one person, one vote.” However, when manipulated through gerrymandering, they can distort representation by favoring one political party over another. For example, in the United States, redistricting based on the decennial census can lead to packed or cracked districts that advantage the dominant party in the state legislature, weakening fair competition and marginalizing voter influence in certain communities while entrenching power in others.

Describe two methods used in gerrymandering and explain how each method impacts electoral outcomes.

Two common methods of gerrymandering are cracking and packing. Cracking spreads voters of a specific demographic or political group across many districts, preventing them from achieving a majority in any. This weakens their overall electoral influence. Packing concentrates the group into a single district, allowing them to win one seat overwhelmingly while diluting their impact in neighboring districts. Both methods manipulate district boundaries to favor one political party, resulting in disproportionate representation. These practices reduce electoral competitiveness, discourage voter turnout, and create legislatures that may not reflect the true preferences of the population.