Agriculture is the deliberate cultivation of crops and raising of livestock for sustenance and economic gain, forming the foundation of human civilization and land-use patterns.

What Is Agriculture?

Agriculture is the science, art, and business of cultivating soil, growing crops, and raising animals to produce food, fiber, fuel, and other goods essential for human life. It represents one of the earliest ways humans modified the environment, transforming natural ecosystems into managed landscapes. Agriculture not only meets basic survival needs but also drives economic development, influences social structures, and determines patterns of human settlement and land use.

The two main types of agriculture are subsistence agriculture, where farmers grow food primarily for their own consumption, and commercial agriculture, where crops and livestock are produced primarily for sale and profit. Both types are shaped by numerous factors including physical geography, technology, government policies, and cultural traditions.

Physical Geography and Agricultural Practices

Climate

Climate is perhaps the most significant physical factor affecting agriculture. Temperature, rainfall, humidity, and seasonal patterns determine what crops can be grown and when. Each crop has specific climate requirements for optimal growth.

Tropical climates support crops like sugarcane, rice, bananas, and coffee.

Mediterranean climates are ideal for olives, grapes, and citrus fruits.

Temperate climates are suitable for wheat, corn, soybeans, and barley.

Arid and semi-arid climates may support drought-resistant crops like millet and sorghum or pastoralism.

A mismatch between climate and crop requirements can lead to crop failure or reduced yields unless mitigated by irrigation, greenhouse technology, or crop selection.

Soil

Soil quality directly influences agricultural productivity. Soil is evaluated based on its texture, structure, nutrient content, pH level, and organic matter. Fertile soils, such as loam, offer ideal conditions for plant growth due to their balanced composition of sand, silt, and clay.

Volcanic soils, like those in Java or Kenya, are nutrient-rich and support dense agriculture.

Sandy soils drain quickly and may require irrigation and fertilization.

Acidic or saline soils may limit crop choices or require treatment.

Farmers often apply chemical fertilizers or use organic matter like compost or manure to replenish soil nutrients and enhance fertility.

Topography and Elevation

The shape of the land influences the feasibility of certain agricultural activities.

Flat terrain is preferred for mechanized farming, as it is easier to till, irrigate, and harvest.

Hilly or mountainous terrain is less suitable for machines and may require terracing, especially in rice-producing areas like Southeast Asia.

High elevation areas have cooler temperatures and shorter growing seasons, influencing what crops can thrive.

Topography also impacts soil erosion and water drainage, which can determine long-term sustainability of farming practices.

Water Availability

Water is essential for all forms of agriculture. Rain-fed agriculture depends entirely on natural precipitation, whereas irrigated agriculture supplements or replaces rainfall with artificial water systems.

Proximity to rivers, lakes, or aquifers often determines agricultural intensity.

Arid regions depend on canals, wells, or advanced irrigation methods like drip or pivot irrigation.

Access to reliable water sources increases agricultural resilience but may also lead to over-extraction, salinization, or conflicts over water rights.

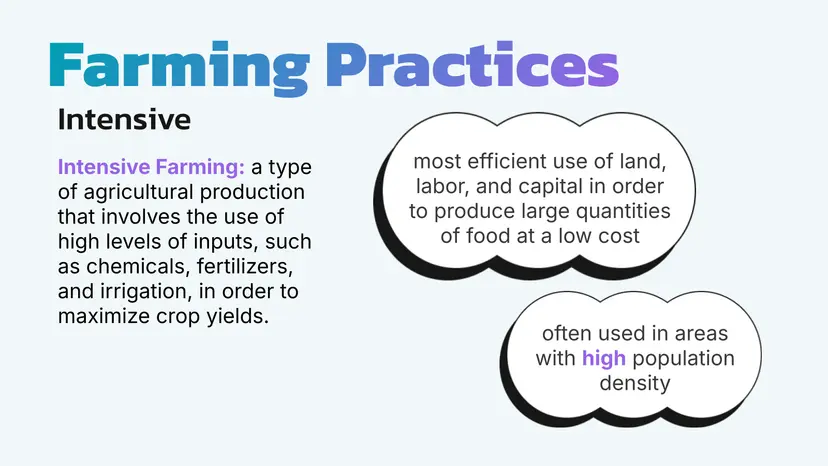

Intensive Farming Practices

Intensive agriculture is characterized by maximizing output from a given area of land using high levels of input. It is common in densely populated or economically developed regions where land is scarce but the demand for food is high.

Characteristics of Intensive Agriculture

High inputs of labor, capital, fertilizers, and technology.

High yields per acre or hectare.

Often focused on market-oriented or export crops.

Mechanization and biotechnology are frequently employed.

Examples of Intensive Agricultural Systems

Monoculture

Monoculture is the practice of growing a single crop over a large area.

Advantages: Simplifies farming operations, allows use of specialized equipment, increases short-term efficiency.

Disadvantages: Depletes soil nutrients, increases vulnerability to pests and diseases, reduces biodiversity.

Examples include vast cornfields in the U.S. Midwest or rice paddies in East Asia.

Irrigation

Irrigation is the artificial application of water to land to assist in crop production.

Methods: Flood irrigation, sprinkler systems, drip irrigation, center pivot irrigation.

Benefits: Allows cultivation in dry regions, stabilizes yields during drought.

Drawbacks: May cause salinization, waterlogging, and depletion of freshwater resources.

Large-scale irrigation is seen in places like the Indus River Valley or California’s Central Valley.

Chemical Fertilizers and Pesticides

Fertilizers provide essential nutrients—nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)—for plant growth.

Pesticides include herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides used to control unwanted organisms.

While effective in boosting yields, these chemicals can cause:

Soil degradation and nutrient imbalance.

Water pollution via runoff.

Harm to non-target species, including pollinators and aquatic life.

Health risks to humans through contamination or residue.

Factory Farming

This refers to the industrialized rearing of animals in confined spaces, such as poultry houses, pig farms, or dairy barns.

Highly efficient for producing meat, eggs, or milk at scale.

Raises concerns about animal welfare, antibiotic overuse, disease spread, and environmental pollution from concentrated animal waste.

Mixed Crop and Livestock Systems

These systems integrate crop cultivation and animal rearing on the same farm.

Animals provide manure to fertilize fields.

Crops supply feed for livestock.

Promotes nutrient cycling and diversification.

More resilient to market fluctuations or climate stress.

This method is common in traditional European farms or U.S. family-run farms.

Plantation Agriculture

A form of commercial farming, plantations grow large quantities of one crop—often for export—on expansive estates.

Examples: Tea in India, coffee in Brazil, rubber in Southeast Asia, sugarcane in the Caribbean.

Usually labor-intensive, sometimes exploitative, and historically tied to colonial systems.

Environmental issues include deforestation, soil exhaustion, and pesticide overuse.

Extensive Farming Practices

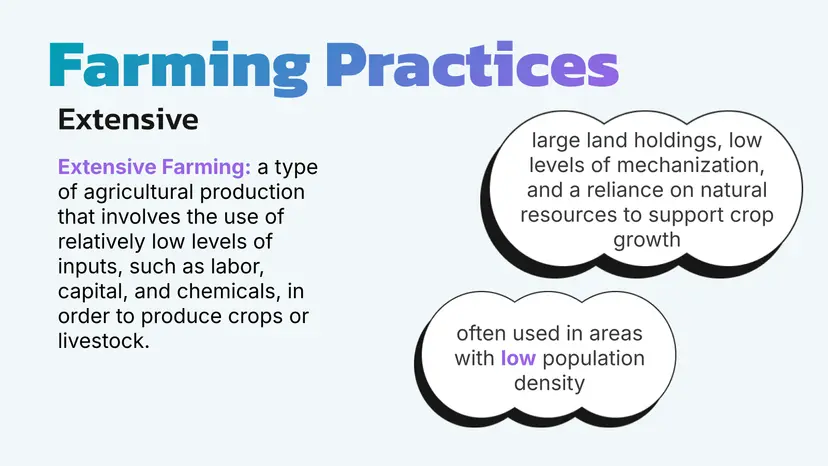

Extensive agriculture relies on large tracts of land with lower input levels. It is practiced in areas with lower population densities and abundant land.

Characteristics of Extensive Agriculture

Low inputs of labor, capital, and technology.

Lower yields per unit of land but often less environmental stress.

Often subsistence-oriented, though some commercial operations exist.

Examples of Extensive Agricultural Systems

Nomadic Herding

A traditional form of livestock raising involving seasonal movement in search of pasture and water.

Practiced in arid and semi-arid zones (e.g., Sahel, Mongolia).

Involves animals like sheep, goats, camels, and reindeer.

Sustainable when population and livestock pressure are low, but vulnerable to overgrazing and desertification.

Pastoralism

More general than nomadic herding, pastoralism may be sedentary or semi-nomadic.

Focused on milk, meat, hides, and wool.

Livestock may be traded or sold to buy grains and other necessities.

Pastoralism supports livelihoods in marginal environments not suited for crops.

Ranching

Ranching involves raising animals, especially cattle and sheep, for commercial sale, often on fenced lands.

Found in countries like the United States, Argentina, and Australia.

Requires large land areas and low labor input per unit area.

May contribute to land degradation and methane emissions.

Shifting Cultivation

A method where small plots of land are cleared (usually by slash-and-burn), cultivated for a few years, then abandoned to regenerate.

Practiced in tropical rainforests (e.g., Amazon Basin, Southeast Asia).

Crops include root vegetables, grains, and fruits.

Sustainable at low population densities, but causes deforestation when expanded.

Subsistence Farming

Involves growing food primarily for the farmer’s own family, with little surplus for trade.

Often includes multiple crop types and small numbers of animals.

Relies on traditional techniques and family labor.

Common in rural parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Central America.

Agricultural Practices and the Human Dimension

Economic Factors

Agricultural practices differ based on a country's economic development:

Developed countries often practice capital-intensive commercial agriculture.

Developing countries may rely more on labor-intensive subsistence agriculture.

Global trade influences what crops are grown, with some regions specializing in cash crops for export rather than local consumption.

Technological Access

Technology affects yields, labor efficiency, and sustainability.

Mechanization (tractors, harvesters)

Biotechnology (genetically modified organisms, hybrid seeds)

Precision farming (GPS-guided equipment, soil sensors)

Access to these technologies is uneven and influences global disparities in agricultural productivity.

Cultural and Religious Influences

Culture shapes dietary preferences and farming choices.

In Hindu communities, cattle may be revered and not slaughtered.

In Islamic regions, pork is avoided.

In Buddhist communities, ethical treatment of animals may influence practices.

These factors determine livestock rearing and crop selection.

Political and Policy Considerations

Governments affect agriculture through:

Subsidies and price supports

Import/export regulations

Land reform policies

Environmental regulations

Such interventions can reshape land use, market behavior, and rural livelihoods.

Vocabulary Review

Agriculture: Human practice of cultivating plants and rearing animals for food, fiber, and other products.

Intensive Agriculture: High-input, high-yield farming on smaller plots.

Extensive Agriculture: Low-input, low-yield farming over larger areas.

Monoculture: Cultivation of a single crop species over large land areas.

Irrigation: Artificial watering of land for agriculture.

Fertilizers: Substances used to add nutrients to soil.

Pesticides: Chemicals that kill pests and protect crops.

Factory Farming: Industrial livestock production in confined settings.

Mixed Crop/Livestock Farming: Integrated system combining crops and animals.

Plantation Agriculture: Large-scale monoculture farming for export.

Nomadic Herding: Moving livestock seasonally in search of grazing.

Pastoralism: Livestock-based agriculture adapted to marginal environments.

Ranching: Commercial livestock grazing on large land tracts.

Shifting Cultivation: Rotational farming with fallow periods.

Subsistence Farming: Farming for family use rather than market sale.

Physical Geography: Natural land features that influence human activity.

FAQ

Government policies can heavily influence agricultural practices, crop choices, and land use by shaping economic incentives and regulatory environments. Through subsidies, governments may encourage the overproduction of certain staple crops or support export-oriented agriculture. Price supports and crop insurance programs reduce farmer risk, which may lead to monoculture practices that can harm soil and biodiversity. Land-use zoning or conservation programs may protect certain areas from overuse or incentivize sustainable farming. Additionally, regulations on chemical usage, water rights, and environmental standards can restrict or redirect how farmers manage their land, impacting both productivity and ecological sustainability.

Subsidies promote crop specialization or food security.

Environmental regulations guide sustainable land practices.

Land reform policies affect farm ownership and land consolidation.

Export tariffs and trade agreements influence what crops are grown.

Urban expansion often leads to the conversion of agricultural land into residential, commercial, or industrial use, especially near city fringes. This process, called urban sprawl, reduces the availability of farmland and may force farmers to either relocate or intensify production on smaller parcels. In peri-urban areas, agricultural land values increase, making it economically attractive to sell rather than farm. Meanwhile, remaining farms may adopt more intensive practices or shift to high-value crops like vegetables or flowers to serve urban markets.

Farmland near cities becomes more expensive and less available.

Land use changes from rural to urban, reducing food production zones.

Farmers may switch to urban agriculture or greenhouse farming.

Conflicts may arise between agriculture and development interests.

Crop diversity is essential for food security, ecological resilience, and adaptability to climate change. A wide range of crops can prevent total crop failure during pest outbreaks, drought, or other environmental stresses. It also supports dietary diversity and soil health. However, crop diversity is threatened by industrialized agriculture and monoculture systems, which favor high-yield commercial varieties over traditional or heirloom crops. Global seed markets are increasingly controlled by a few corporations, limiting access to diverse seeds.

Genetic diversity helps protect against pests and diseases.

Diverse cropping reduces soil exhaustion and erosion.

Monocultures increase vulnerability to crop failure.

Seed privatization and commercialization limit traditional crop use.

Market access determines what crops are grown, how they are produced, and whether farming is subsistence-based or commercial. Farmers near urban centers or export terminals are more likely to grow perishable, high-value crops like fruits, vegetables, or flowers for profit. They may invest in irrigation, packaging, and cold storage. Remote farmers often produce staple crops for local consumption or rely on less perishable goods due to transportation challenges. Limited market access can trap farmers in low-productivity cycles and restrict income opportunities.

Proximity to markets encourages commercial and intensive farming.

Distant farms may rely on extensive or subsistence methods.

Better access leads to more technology adoption and specialization.

Poor infrastructure limits farm income and production diversity.

Intensive agriculture can increase food production but often comes with significant environmental costs. Overuse of chemical fertilizers leads to nutrient runoff, which causes water pollution and dead zones in aquatic ecosystems. Pesticide use can harm non-target species, including pollinators and beneficial insects. Monocultures reduce biodiversity and increase vulnerability to pests and diseases. Irrigation can lead to soil salinization and depletion of freshwater resources. These impacts reduce soil health, degrade ecosystems, and threaten long-term food security if not managed sustainably.

Fertilizer runoff leads to eutrophication in lakes and rivers.

Pesticides disrupt ecosystems and contaminate food chains.

Soil erosion and compaction reduce agricultural productivity.

Groundwater depletion affects long-term water availability.

Practice Questions

Explain how physical geography influences the type of agricultural practices used in a specific region. Provide an example to support your response.

Physical geography—including climate, soil, topography, and water availability—directly influences agricultural practices. For instance, in Southeast Asia, the warm, humid tropical climate and flat river valleys with fertile alluvial soils support intensive rice cultivation. Farmers use wet-field (paddy) systems that rely on abundant rainfall and seasonal flooding. In contrast, arid regions like the Middle East often practice pastoralism or irrigated agriculture due to limited precipitation. These environmental conditions shape what crops can be grown, how land is used, and what technologies are needed to support farming. Understanding physical geography is essential for analyzing regional agricultural patterns and sustainability.

Describe one intensive and one extensive farming practice and explain how each reflects land use and resource availability.

Intensive farming uses high inputs of labor, capital, and technology on smaller plots to maximize yield. For example, plantation agriculture in Brazil grows export crops like coffee with heavy fertilizer use and mechanization. This reflects limited land availability and a focus on commercial profit. In contrast, extensive farming uses lower inputs on large land areas. An example is cattle ranching in Australia, where livestock graze over vast dry grasslands. This method reflects abundant land and scarce labor or water resources. The contrast in these practices demonstrates how land use intensity aligns with regional population density and environmental conditions.