Agriculture began in distinct regions thousands of years ago and spread globally, revolutionizing human settlement, economic systems, and environmental interaction.

The Evolution of Agriculture

Agriculture has continuously evolved through the influence of geography, culture, and innovation. Understanding its origins and diffusion helps explain current food production patterns and global disparities in land use and development.

From Foraging to Farming

The First Agricultural Revolution, also known as the Neolithic Revolution, marked a pivotal change in human history. Around 10,000 BCE, humans began to shift from nomadic hunting and gathering to sedentary farming lifestyles. This transformation was not sudden but took place gradually in several parts of the world.

People began to observe plant cycles, learning that seeds could be planted to grow crops.

Humans began to domesticate animals, selecting for traits like tameness, productivity, and size.

This change enabled permanent settlements, leading to population growth, job specialization, social hierarchies, and eventually cities.

Societies gained the ability to store surplus food, which increased food security and allowed for non-agricultural pursuits such as trade, religion, and governance.

Agricultural Hearths

An agricultural hearth is a geographic region where agriculture first emerged independently. These areas were crucial for the domestication of various plants and animals and later served as centers of diffusion.

Fertile Crescent / Mesopotamia

Located in the Middle East between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, this region is widely recognized as the earliest center of agriculture.

Crops domesticated: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, lentils, olives.

Animals domesticated: cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and dogs.

The Sumerians, among the first civilizations in this region, developed irrigation, plows, and writing systems such as cuneiform.

Farmers used floodplains for fertile soil and devised canals and dikes to regulate water.

The Fertile Crescent saw the first large-scale transition from foraging to food production and supported early urban life.

Nile River Valley

This hearth emerged around the Nile River in northeastern Africa, especially in present-day Egypt and Sudan.

The annual flooding of the Nile deposited rich silt, rejuvenating the soil and enabling predictable agriculture.

Crops: flax, lentils, chickpeas, beans, wheat, barley.

Livestock: cattle, goats, sheep, pigs.

Advanced irrigation and drainage systems supported high yields.

Enabled the rise of Ancient Egypt, a powerful civilization with centralized control over agriculture and food distribution.

Indus River Valley

Situated in present-day Pakistan and northwest India, the Indus River Valley was another early center of agriculture.

Associated with urban centers such as Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro (c. 2500–1900 BCE).

Crops: wheat, barley, mustard, peas, cotton, sesame.

Animals: water buffalo, chickens, pigs, cattle, goats.

The civilization developed grid-planned cities, drainage systems, and organized grain storage, indicating a highly managed agricultural system.

Rivers were used not only for irrigation but also for trade routes and transportation.

East Asia

Agriculture independently developed in parts of China, especially the Yellow River (Huang He) and Yangtze River Valleys.

Northern China (Yellow River): domesticated millet and soybeans.

Southern China (Yangtze River): domesticated rice.

Water buffaloes were used for labor, while pigs and chickens were common livestock.

Early Chinese dynasties such as the Xia and Shang implemented agricultural innovations including terracing and irrigation.

Tools made of bronze and wood were utilized to farm intensively cultivated lands.

From China, these practices spread to Korea and Japan, facilitating the expansion of wet-rice cultivation.

Southwest Asia

Beyond Mesopotamia, parts of modern-day Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the Arabian Peninsula also served as agricultural hearths.

Crops: barley, wheat, lentils, dates, and olives.

Animals: pigs, goats, sheep, cattle, dogs — more species were domesticated here than in any other region.

Civilizations such as the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Persians flourished through organized agriculture and widespread use of canals and irrigation basins.

Religious beliefs often influenced crop selection and livestock practices in this region.

Mesoamerica (Central America)

Mesoamerica includes parts of southern Mexico and Central America and is home to the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations.

Crops: maize (corn), beans, squash, chili peppers, cotton.

Maize was particularly transformative and became a staple crop throughout the Americas.

Farming techniques: terracing, raised fields, and chinampas (floating gardens) increased efficiency and land use.

Although lacking large domesticated animals, small animals such as turkeys and dogs were raised.

Complex calendars and ceremonies were often tied to agricultural cycles, revealing the spiritual significance of farming.

Andes and Amazonia (South America)

In the Andes Mountains, agriculture developed in highland and coastal regions of Peru and Bolivia.

Crops: potatoes, quinoa, sweet potatoes, peanuts.

Domesticated animals: llamas and alpacas used for transport and wool.

Developed terrace farming to reduce erosion and maximize mountain cultivation.

Irrigation systems channeled water from glacial melt and rainfall.

Coastal Peru also produced cotton, used in textiles and trade networks.

Sub-Saharan Africa

This vast region developed agriculture independently with climate and ecological diversity shaping different farming systems.

Crops: yams, millet, sorghum, cowpeas.

The Sahel region saw the rise of millet and sorghum cultivation.

The Bantu Migration (c. 1000 BCE – 1500 CE) spread ironworking and farming techniques throughout central and southern Africa.

The environment required adaptations such as shifting cultivation (slash-and-burn) and use of drought-tolerant crops.

Early domestication of guinea fowl and local use of goats and cattle added to food systems.

Diffusion of Agriculture

Once agriculture was established in these hearths, it diffused outward, reshaping societies, economies, and landscapes.

Types of Agricultural Diffusion

Contagious diffusion: The spread of farming methods through local contact (e.g., neighboring villages).

Relocation diffusion: Movement of people who brought agricultural knowledge with them (e.g., Bantu Migration).

Hierarchical diffusion: Spread from political or religious leaders to surrounding areas (e.g., irrigation techniques promoted by rulers).

The First Agricultural Revolution

Initiated around 10,000 BCE, this revolution saw a global shift from subsistence hunting to farming.

Innovations such as domestication, seed cultivation, and land ownership were essential.

Practices diffused from the Fertile Crescent to Europe, Central Asia, and North Africa.

The surplus in food allowed for trade, population expansion, and urbanization.

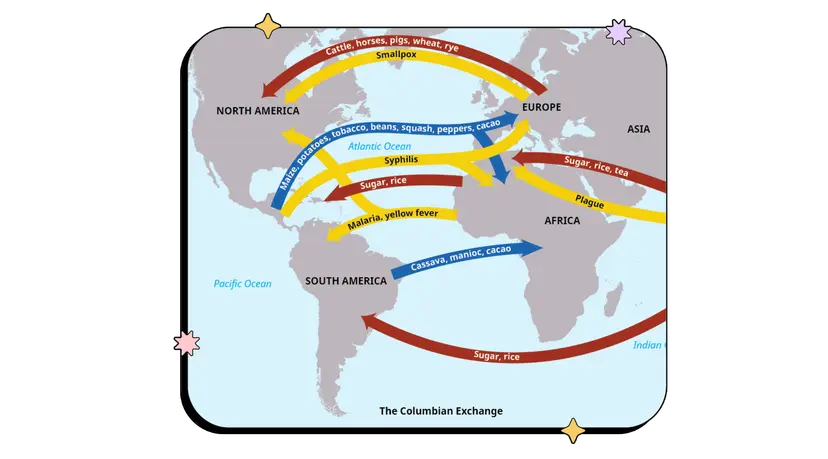

The Columbian Exchange

One of the most significant instances of diffusion, the Columbian Exchange (15th–16th centuries), refers to the transatlantic movement of goods, crops, people, and diseases following European exploration.

From the Americas to Europe, Africa, and Asia:

Crops: maize, potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, tobacco, vanilla.

Animals: turkeys, llamas.

From Europe, Africa, and Asia to the Americas:

Crops: wheat, rice, barley, sugarcane, coffee.

Animals: horses, pigs, sheep, cattle.

Technologies: iron tools, firearms, plows.

This diffusion revolutionized global agriculture, increased caloric intake, and altered food habits on a global scale.

Negative consequences included the spread of diseases such as smallpox, which devastated Indigenous populations.

Domestication of Plants and Animals

The process of domestication involved selecting organisms for traits useful to humans. Over time, these traits became genetically stable through breeding.

Domesticated Plants

Farmers selected plants based on:

High yield per plant.

Flavor and storage qualities.

Drought or pest resistance.

Examples of major domesticated crops:

Wheat and barley (Middle East)

Rice and millet (East Asia)

Maize, beans, squash (Mesoamerica)

Sorghum and yams (Africa)

Potatoes and quinoa (Andes)

Domesticated Animals

Animals were domesticated for:

Meat and dairy (e.g., cattle, goats)

Labor (e.g., oxen, horses)

Clothing and textiles (e.g., sheep, alpacas)

Early domesticated animals include:

Dogs – earliest domesticated species, used for hunting and protection.

Sheep and goats – manageable, small, high-reproduction rates.

Pigs and cattle – high-fat meat sources.

Chickens – prolific egg layers.

The success of early agriculture depended on the symbiotic relationship between plants and animals, supporting increasingly complex societies.

Cultural and Environmental Influences

As agriculture spread, it was adapted to local conditions and cultural practices.

In mountainous regions like the Andes and Southeast Asia, people practiced terrace farming to prevent erosion and manage water.

In tropical rainforests, slash-and-burn agriculture cleared fields for temporary use.

In arid regions like Mesopotamia and Egypt, large-scale irrigation systems developed to support crop growth.

Religious and cultural practices often influenced dietary rules, such as taboos against certain animals or food preparation methods.

FAQ

Environmental conditions played a crucial role in determining where agriculture first developed. Early agricultural hearths emerged in regions with favorable climate, fertile soil, and access to fresh water, which supported plant growth and animal domestication.

Areas like river valleys provided seasonal flooding, which enriched the soil with nutrients.

Temperate climates with distinct seasons promoted predictable growing cycles.

Natural biodiversity allowed for the selection of a wide variety of plants and animals for domestication.

Proximity to water sources enabled irrigation, which expanded cultivation beyond rain-fed agriculture.

Elevation, rainfall patterns, and soil composition also determined the types of crops that could be grown successfully, leading to region-specific agricultural systems.

In early agricultural societies, gender roles were shaped by labor divisions, with men and women both contributing significantly but often in different capacities.

Women were likely the first plant domesticators, as they gathered wild plants and observed growth cycles.

They experimented with seeds and planting, playing a foundational role in the development of early horticulture.

Men were more commonly involved in animal domestication, hunting, and later, in more physically intensive farming tasks.

As agriculture intensified, these divisions often solidified, influencing social structures and the emergence of patriarchal systems.

Over time, agricultural surpluses allowed for occupational specialization, reducing women's traditional roles in food production in many societies.

Agricultural diffusion had profound ecological effects on the landscapes it reached, often altering native biodiversity.

Introduced species could become invasive, outcompeting native plants and disrupting existing ecosystems.

Livestock such as cattle and sheep contributed to overgrazing, leading to soil erosion and desertification in some regions.

Deforestation for farmland reduced native forest habitats, impacting indigenous flora and fauna.

New agricultural practices modified water use patterns, altering wetlands and watersheds.

While some native species were incorporated into farming systems, many others were marginalized or driven to extinction due to habitat loss and the monoculture practices that often accompanied agricultural expansion.

Certain regions never developed agriculture independently due to a mix of environmental, biological, and social factors.

Some areas lacked suitable wild plants or animals that could be domesticated easily.

Harsh environments (e.g., deserts, tundra) lacked adequate rainfall, fertile soil, or growing seasons.

In places with abundant wild food resources, there was less pressure to develop agriculture.

Some mobile societies found that foraging and pastoralism were more efficient in their specific ecological contexts.

Cultural preferences and social organization may have prioritized mobility, spiritual practices, or trading systems over sedentary farming, delaying or preventing the shift to agriculture.

Agriculture deeply influenced spiritual beliefs, cosmologies, and rituals in early societies.

Many early cultures developed gods or spirits associated with crops, rain, fertility, and seasons.

Agricultural cycles influenced the timing of festivals and ceremonies, often aligned with planting and harvesting.

Burial sites, temples, and monumental architecture were sometimes built in alignment with solar or lunar calendars, reflecting seasonal cycles crucial for farming.

Fertility symbols and earth deities emerged in Neolithic societies, indicating a spiritual connection to soil and sustenance.

Offerings and sacrifices were performed to ensure good harvests, reflecting the interdependence of agriculture and religion in early cultural development.

Practice Questions

Explain how early agricultural hearths contributed to the diffusion of domesticated crops and animals across the globe. Provide one specific example of a hearth and the crops or animals associated with it.

Early agricultural hearths were centers of innovation where domestication of crops and animals first occurred. These hearths influenced surrounding regions through contagious and relocation diffusion. As people migrated or traded, they carried agricultural knowledge, seeds, and livestock, spreading practices to new areas. For example, the Fertile Crescent in Southwest Asia domesticated wheat, barley, goats, and sheep. These spread to Europe and North Africa through migration and trade routes. The diffusion from such hearths led to permanent settlements, increased food security, and the growth of civilizations, fundamentally transforming societies through sustained agricultural production and environmental adaptation.

Describe one way in which the Columbian Exchange transformed agricultural practices in the Eastern Hemisphere. Provide specific examples of crops or animals involved.

The Columbian Exchange brought transformative agricultural changes to the Eastern Hemisphere by introducing nutrient-rich crops from the Americas. One major example is the introduction of the potato to Europe, which became a staple food due to its high yield and adaptability. This crop improved food security, supported population growth, and reduced famine. Similarly, maize from Mesoamerica spread to Africa and Asia, becoming an essential crop in many regions. The influx of new crops diversified diets, shifted farming practices, and restructured economies. These agricultural transformations were crucial in shaping modern global food systems and expanding agricultural productivity worldwide.