The Second Agricultural Revolution transformed agricultural practices through technological innovations, social changes, and economic developments, laying the foundation for industrialization and global agricultural systems.

What Was the Second Agricultural Revolution?

The Second Agricultural Revolution, often referred to as the British Agricultural Revolution, was a period of significant transformation in agricultural production. It began in Britain around the 16th century and intensified through the 18th and early 19th centuries. Unlike the First Agricultural Revolution, which centered on the initial domestication of plants and animals, the Second Agricultural Revolution focused on increasing efficiency, productivity, and commercialization in farming.

This revolution was characterized by a series of interconnected innovations in farming techniques, land management, and mechanization. It also occurred alongside and contributed to the Industrial Revolution, providing the labor, food surplus, and economic momentum that supported rapid industrial and urban development.

The Second Agricultural Revolution was not a single event but a collection of shifts that evolved over time. It reflected a change from subsistence agriculture to commercial agriculture, where farmers produced crops and livestock for market exchange rather than personal consumption.

Key Innovations and Techniques

The Enclosure Movement

One of the most significant social and structural changes of the Second Agricultural Revolution was the Enclosure Movement. In pre-modern England, many rural communities practiced open-field agriculture, where land was shared among villagers and worked communally. The enclosure movement ended this system by consolidating scattered strips of land into privately owned, enclosed plots.

Enclosures allowed landowners to implement new techniques and invest in improving their land without needing communal consent.

Hedgerows and fences were used to mark property boundaries, enabling more efficient control over livestock and crop management.

Enclosure laws passed by the British Parliament legalized the process, favoring wealthy landowners and displacing many small farmers.

These displaced farmers often became wage laborers on large farms or migrated to urban areas seeking work in factories, fueling urbanization.

Enclosure greatly improved agricultural productivity, but it also deepened social inequality and transformed the rural landscape.

The Four-Field System and Crop Rotation

Another crucial development was the shift to the four-field crop rotation system, which replaced the traditional medieval three-field method.

The four-field system rotated wheat, turnips, barley, and clover (or ryegrass) on the same plot of land.

This method ensured that no field lay fallow, which kept land continuously in use and increased productivity.

Turnips and clover helped replenish soil nutrients, particularly nitrogen, while also providing fodder for livestock.

This innovation supported livestock year-round, reducing seasonal shortages of meat and dairy and enhancing protein in rural diets.

Crop rotation reduced soil exhaustion and allowed land to be more intensively cultivated, making it possible to support larger populations.

Selective Breeding of Livestock

Before the revolution, livestock was raised more for endurance and survival than productivity. The Second Agricultural Revolution introduced selective breeding, where animals were bred specifically for desirable traits.

Robert Bakewell, a prominent figure in agricultural reform, used selective breeding to improve sheep and cattle.

Traits selected for included larger size, faster growth, higher milk yield, and better meat quality.

Improved livestock led to greater quantities of wool, milk, and meat, further contributing to economic growth and food availability.

The process laid the foundation for scientific livestock management and genetics-based agriculture in later periods.

Selective breeding also complemented crop rotation, as better-fed livestock produced more manure, which in turn enriched soil fertility.

Mechanization of Agriculture

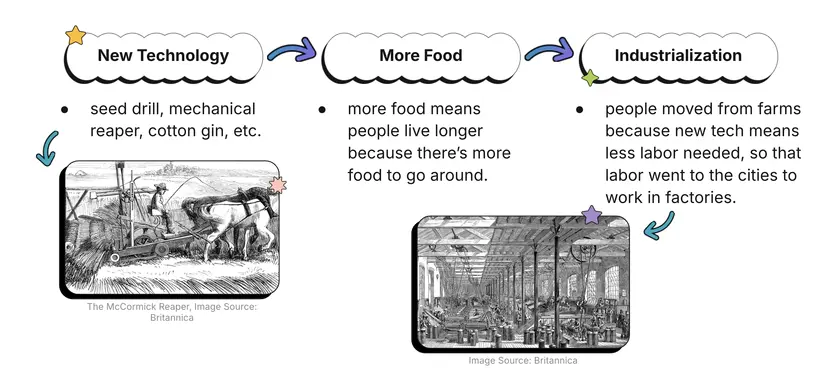

One of the most transformative features of the Second Agricultural Revolution was the introduction of machines, which replaced manual labor and animal power in many farming tasks.

Seed drill: Invented by Jethro Tull in the early 18th century, this machine allowed for the systematic planting of seeds in neat rows at correct depths, improving germination rates and reducing waste.

Mechanical threshers: These machines separated grain from stalks and husks, reducing the labor and time required during harvest.

Mechanical reapers and plows improved by industrial engineers were gradually adopted, increasing the area a single farmer could cultivate.

Mechanization led to labor displacement but dramatically boosted agricultural output and efficiency.

These innovations made it possible to farm larger areas with fewer workers, freeing laborers for industrial employment and shifting the demographic balance between rural and urban areas.

Impacts on Society and Economy

Increased Agricultural Productivity

All these advancements—mechanization, improved land use, crop rotation, and animal husbandry—converged to produce a dramatic increase in food production.

Farms were able to support more people with fewer workers, allowing populations to grow without the threat of widespread famine.

Larger yields led to food surpluses, which were stored, traded, and transported to urban areas.

Malnutrition and famine became less frequent in regions that adopted new agricultural techniques.

The increased productivity also reduced the cost of food, making diets more diverse and accessible to a larger segment of the population.

Urbanization and Labor Shifts

The Second Agricultural Revolution was a key contributor to the rise of urban industrial centers.

As farms required fewer laborers due to enclosure and mechanization, rural populations moved to cities.

These rural-urban migrants provided the labor force necessary for factories, textile mills, and other emerging industries during the Industrial Revolution.

This migration led to the rapid growth of cities and the development of dense urban settlements, shifting population patterns permanently.

This redistribution of labor altered traditional family structures, economic roles, and societal dynamics, laying the groundwork for modern urban economies.

Social Changes in Land Ownership and Labor

The revolution restructured rural society, consolidating power among wealthy landowners and weakening the economic position of small-scale farmers.

Land ownership became more concentrated in the hands of the elite.

Many peasants became tenant farmers or agricultural laborers, working for wages rather than owning land.

Social mobility was restricted, but a market-driven agricultural economy emerged, characterized by investment, competition, and profit maximization.

A new class of commercial farmers and agrarian entrepreneurs arose, promoting innovation and efficiency.

These shifts created long-lasting inequalities but also stimulated capital formation and investment in rural infrastructure.

Dietary Improvements and Public Health

As food production became more efficient and accessible, significant improvements in diet and health occurred.

Potatoes, rich in calories and nutrients, became a staple crop throughout Europe.

Variety in available food increased, with more access to dairy, protein, and vegetables.

Infant mortality declined, and life expectancy increased, thanks to better nourishment and reduced food scarcity.

Urban populations, especially, benefited from consistent food supplies transported from rural areas via improved infrastructure.

Though malnutrition still existed, the general population experienced a healthier, more stable standard of living compared to previous centuries.

Environmental Impacts

While the revolution improved productivity, it also introduced ecological disruptions.

Loss of biodiversity occurred due to monoculture farming and the focus on high-yield crops.

Deforestation and drainage of wetlands were common practices to create more arable land.

Soil erosion increased in areas with overgrazing or poor crop rotation.

The intensified use of manure enriched fields but also contributed to water pollution in dense agricultural regions.

These impacts foreshadowed some of the environmental concerns of the modern era, emphasizing the need for balanced agricultural development.

Reasons It Originated in Britain

The Second Agricultural Revolution began in Britain due to several key factors:

Stable political system that supported private property rights and market regulation.

A rising urban middle class that created new demand for agricultural goods.

Access to colonial markets and global trade, which allowed agricultural surplus to fuel broader economic growth.

An active scientific community, including individuals like Jethro Tull and Robert Bakewell, who conducted agricultural experiments and shared findings.

Dense network of ports, roads, and rivers that facilitated transport of goods, tools, and livestock.

The combination of capital investment, scientific curiosity, and market access enabled Britain to become the epicenter of agricultural modernization.

Legacy and Global Diffusion

Though rooted in Britain, the revolution spread through Europe and North America, reaching global influence by the 19th century.

France, Germany, and the Netherlands adopted selective breeding and mechanization.

In the United States, innovations in the Midwest transformed vast tracts of land into productive farmland.

These changes encouraged the development of commercial farming systems, with emphasis on export and large-scale operations.

Concepts like crop rotation, enclosure, and mechanization became global standards in agricultural practice.

The revolution set the stage for the Green Revolution in the 20th century and the continued evolution of industrial agriculture.

Key Terms and Concepts to Remember

Enclosure Movement: Privatization of common lands to create more efficient, market-oriented farms.

Four-Field System: A method of crop rotation that preserved soil fertility and increased productivity.

Selective Breeding: Choosing animals with desirable traits to produce stronger, more productive offspring.

Seed Drill: A mechanical planter that revolutionized the sowing of seeds.

Threshing Machine: A mechanized device that separated grain from stalks.

Commercial Agriculture: Farming primarily for market sale, rather than for local or personal use.

Urbanization: The migration of rural populations to cities, leading to industrial and demographic change.

Rural-Urban Migration: Movement from farms to cities due to changing economic opportunities.

Increased Productivity: Greater food output from the same or reduced amount of labor.

Dietary Improvement: Enhanced nutrition and food security leading to population growth and public health advances.

FAQ

The Second Agricultural Revolution significantly altered traditional labor roles, including those of women. As farming became more mechanized and commercialized, the role of women in agriculture decreased in some regions, especially in Britain and Western Europe.

Previously, women participated heavily in planting, weeding, harvesting, and food preparation.

Mechanization reduced the need for labor-intensive handwork, which marginalized women in field labor.

As agriculture shifted to male-dominated machine operation and land management, women often moved to domestic roles or joined informal labor in cities.

However, in some rural areas, women continued to manage subsistence gardens and animal care.

The revolution reinforced gender divisions in labor, particularly in emerging industrial societies, shaping long-term social and economic structures.

Transportation played a vital role in expanding the impact of the Second Agricultural Revolution. Improved infrastructure allowed for the efficient movement of agricultural goods, tools, and labor.

The development of all-weather roads allowed year-round transport of goods between rural and urban areas.

Canals were constructed in Britain to transport heavy goods like grain, manure, and machinery at lower costs.

Horse-drawn carts and wagons became more reliable with better road surfaces and suspension technologies.

Early rail systems in the late 18th and early 19th centuries further accelerated trade and urban food supply.

Faster transportation meant that perishable goods could reach urban markets before spoiling, helping expand crop diversity and commercial agriculture.

The innovations of the Second Agricultural Revolution were exported to colonial territories, altering traditional agricultural systems and land use in those regions.

European powers applied enclosure-style systems in colonies, often displacing indigenous farmers and communal practices.

Cash crop economies emerged, where colonies grew monoculture crops like cotton, tea, or sugar for export, not local consumption.

Colonists introduced mechanized tools, irrigation systems, and European crops to colonized lands, reshaping the physical landscape.

Traditional polyculture and subsistence farming were often replaced by commercial, European-style agriculture.

This shift disrupted local food systems, reduced food security, and contributed to long-term economic dependency on European markets.

The Enlightenment period fostered a climate of experimentation and innovation that directly influenced agricultural development during the Second Agricultural Revolution.

Thinkers emphasized rational planning, empirical observation, and systematic improvement, which were applied to farming.

Agriculturalists like Arthur Young and Robert Bakewell conducted and published experiments on crop yields and breeding.

Scientific journals and agricultural societies shared information widely, encouraging farmers to test new methods.

Enlightenment ideals promoted education and innovation, pushing agriculture toward a data-driven, results-oriented discipline.

This mindset laid the groundwork for the emergence of agronomy as a science and encouraged long-term improvements in productivity and land use.

The transformation of agricultural practices during the Second Agricultural Revolution led to significant changes in the rural built environment and landscape.

Farmhouses and barns were redesigned to accommodate larger equipment and greater yields.

Grain storage silos, animal enclosures, and new irrigation systems became standard on many farms.

The widespread use of hedgerows and stone walls marked enclosed fields, replacing open strips of land.

Rural settlements became more dispersed, as farm families no longer needed to live in clustered villages under communal systems.

The visual organization of rural Britain shifted from irregular shared plots to neatly arranged, geometric fields aligned with roads and boundaries, reflecting the move toward privatized and efficient land use.

Practice Questions

Describe two innovations of the Second Agricultural Revolution and explain how each contributed to increased agricultural productivity.

The Second Agricultural Revolution introduced major innovations that boosted productivity. First, the seed drill, invented by Jethro Tull, allowed farmers to plant seeds in evenly spaced rows at proper depth, improving germination rates and reducing seed waste. This made planting more efficient and increased crop yields. Second, the four-field crop rotation system replaced the traditional three-field system by incorporating turnips and clover, which replenished soil nutrients and provided fodder for livestock. This allowed continuous cultivation without exhausting the soil, leading to more frequent harvests and higher productivity. Both innovations transformed agriculture from subsistence to surplus production.

Explain how the Enclosure Movement during the Second Agricultural Revolution affected rural populations and contributed to urbanization.

The Enclosure Movement consolidated small, communal farming plots into larger, privately owned fields, which allowed landowners to implement efficient farming practices. While this increased agricultural output, it displaced many small farmers and laborers who had previously relied on common land for subsistence. As a result, these rural residents were forced to seek employment elsewhere, leading to a mass migration to urban areas. This rural-to-urban shift provided the growing industrial cities with a labor force, contributing significantly to the urbanization process that supported the Industrial Revolution. Thus, enclosure played a critical role in transforming both agricultural and demographic patterns.