Agricultural production regions are geographic areas where specific farming methods dominate, shaped by climate, economic systems, land values, and cultural practices.

Key Environmental and Economic Determinants

Agricultural practices vary greatly from one region to another based on:

Climate conditions: Temperature ranges, precipitation patterns, and seasonal variation determine crop suitability and livestock types.

Soil characteristics: The fertility, drainage, and nutrient profile of soils influence what can be grown and how often fields must be rotated or rested.

Topography: Sloped land can restrict machinery use, favoring labor-intensive practices; flat plains allow for mechanized, large-scale agriculture.

Water access: Reliable irrigation systems allow for year-round crop cultivation in arid or variable climates.

Market proximity: Closer proximity to cities or transportation hubs increases land value and supports perishable, high-value farming.

Labor and capital: Access to labor (manual or mechanized) and investment capital influences the intensity and type of agriculture practiced.

Major Global Agricultural Production Regions

Midwest, United States

Known for its Corn Belt and Wheat Belt, the Midwest has fertile mollisol soils and a temperate continental climate ideal for cereal crops.

Main crops include corn, soybeans, and wheat.

Farming is commercial, highly mechanized, and integrated into global supply chains.

Farming infrastructure includes grain elevators, ethanol plants, and intermodal transport systems.

Advanced technology such as GPS-guided tractors and aerial drones optimize inputs and yields.

Prairie Provinces, Canada

Includes Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

Characterized by extensive grain farming, particularly wheat, barley, and canola.

Harsh winters and short growing seasons are offset by long daylight hours in summer.

Farms cover thousands of acres and use minimal labor relative to land area.

Crop insurance and federal subsidies support farming under unpredictable climatic conditions.

Yangtze River Valley, China

A densely populated agricultural heartland with a humid subtropical climate.

Dominated by rice cultivation in paddies, followed by wheat, rapeseed, and vegetables.

Incorporates traditional double-cropping and intercropping to maximize land use.

Farming remains labor-intensive, though increasing mechanization is evident in wealthier provinces.

High food demand due to population density drives intensive use of every cultivable plot.

Po River Valley, Italy

Mediterranean climate supports diversified production: wheat, rice, grapes, and corn.

Irrigation is common due to seasonal droughts.

Known for vineyards, fruit orchards, and dairy farming.

Agribusiness includes connections to Italy’s wine, cheese, and pasta industries.

Fertile alluvial soils and flat land support high-yield, commercial farming.

Pampas, Argentina

Flat plains with deep, fertile mollisols and moderate rainfall.

Produces soybeans, wheat, sunflowers, and beef cattle.

Farms are export-oriented and part of Argentina’s global agro-export economy.

Mechanization and genetically modified crops are widespread.

Vulnerable to global commodity price fluctuations and currency devaluation.

Brazilian Cerrado and Highlands

Tropical savanna biome transformed into productive farmland using lime treatments to correct soil pH.

Major products include soybeans, sugarcane, coffee, and cotton.

Expanding agriculture often conflicts with conservation of biodiversity.

Brazil is a top global exporter of soybeans and beef.

Infrastructure improvements, such as highways and railroads, have linked interior farmlands to ports.

Agricultural Practices: Systems and Structures

Subsistence Farming

Practiced in rural LDCs, where food is produced mainly for family consumption.

Farms are small-scale, labor-intensive, and depend heavily on rainfall.

Tools are simple (hand tools, animal plows), and inputs are low (few fertilizers or pesticides).

Crop diversity helps spread risk and provides balanced diets.

Example: In rural Nepal, terraced fields support rice, lentils, and vegetables. Goats and chickens provide dairy and protein. Families use compost, maintain seed banks, and depend on seasonal rainfall patterns.

Commercial Farming

Oriented toward maximizing profit through the sale of products to local, national, or global markets.

Requires large capital investments and relies on mechanization, chemical inputs, and high-efficiency logistics.

Production is often specialized (monoculture), and farms are managed as businesses.

Example: A California almond farm uses satellite imagery for water management, harvests mechanically, and exports to Europe and Asia. It employs seasonal migrant labor and reinvests in processing facilities for added value.

Intensive vs. Extensive Farming

Intensive agriculture:

Found in densely populated or high land-value areas.

High input per unit of land: fertilizers, pesticides, labor, or machinery.

Examples: rice farming in Southeast Asia, greenhouses in the Netherlands.

Extensive agriculture:

Found in regions with abundant land and low population density.

Low input per unit of land, often uses natural rainfall and limited labor.

Examples: cattle ranching in Australia, wheat farming in Kazakhstan.

Monocropping and Associated Impacts

Monocropping, or monoculture, involves the repeated planting of a single crop across large areas.

Advantages:

Simplifies planting, management, and harvesting.

Enhances economies of scale and reduces short-term costs.

Disadvantages:

Promotes pest and disease outbreaks.

Depletes soil nutrients, requiring heavy fertilizer use.

Reduces biodiversity and increases ecological vulnerability.

Major monoculture crops:

Corn: U.S. Midwest

Soybeans: Brazil, Argentina, U.S.

Wheat: Russia, Canada, U.S.

Cotton: Pakistan, U.S., India

Palm oil: Malaysia, Indonesia

Sustainable responses:

Crop rotation: Alternating crop types annually to restore soil health.

Polyculture and intercropping: Combining crops with different root depths or growth cycles to maximize resource use.

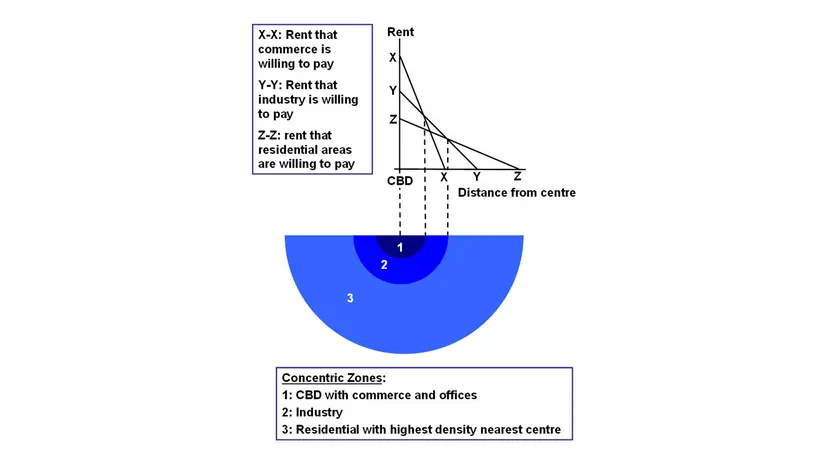

Bid-Rent Theory and Agricultural Zoning

Image Source: cronodon.com

The Bid-Rent Theory describes how land value decreases as one moves away from a central business district (CBD), affecting agricultural land use.

Core Assumption: All other things equal, the closer land is to the CBD, the more expensive it becomes.

Implication: Land near the CBD is used for high-value activities like perishable farming, market gardening, or floriculture.

Farther out: Land is cheaper and suited to grain production, grazing, and forestry.

Example:

Strawberry farms cluster around major cities like Los Angeles due to perishability.

Dairy farms situate in suburban zones to maintain access to cold storage and processing plants.

Grain fields lie farther away, relying on rail and truck transport to reach distant markets.

Key characteristics:

Commerce: Competes for inner-city land due to access to customers.

Industry: Needs moderately priced land with good transport access.

Residential: Spreads outward based on commuting costs and affordability.

Agriculture: Typically located in peripheral zones unless high-value crops justify land costs.

Theory assumptions:

A flat, featureless plain (no physical barriers).

Equal transportation access in all directions.

Single market center (CBD).

All land users behave rationally and seek profit maximization.

Spatial Patterns in Agricultural Production

Farming regions are embedded in broader spatial and economic networks:

Core-periphery relationships: Agricultural zones often serve urban cores with fresh or bulk commodities.

Global commodity chains: Raw agricultural goods from developing nations are processed and consumed in wealthier countries.

Export-oriented zones: Regions like Chile’s Central Valley or Kenya’s flower industry tailor crops to international demand.

Market gardening zones:

Found on city outskirts, growing tomatoes, lettuce, and herbs.

Use hoop houses, greenhouses, and hydroponics for year-round supply.

Sold in farmers’ markets, supermarkets, and CSA (community-supported agriculture) programs.

Livestock regions:

Semi-arid zones like the U.S. Great Plains and Australian outback favor cattle and sheep ranching.

Feedlots and factory farms concentrate animals to reduce land use and raise output.

Specialty crops:

Coffee: Ethiopia, Colombia, Vietnam

Tea: India, Kenya, Sri Lanka

Wine grapes: France, Chile, California

Threats to Agricultural Production Regions

While global agricultural productivity has increased, numerous challenges endanger long-term sustainability:

Soil erosion and salinization from irrigation and over-plowing.

Aquifer depletion in high-input areas like India’s Punjab or California’s Central Valley.

Climate change affecting rainfall patterns, growing seasons, and crop viability.

Urban sprawl converting prime farmland into housing or industry.

Economic volatility making farmers dependent on fluctuating commodity markets.

Invasive species and pest outbreaks due to monoculture practices.

FAQ

Climate zones determine the kinds of crops and livestock that can thrive in a particular region, impacting both the productivity and sustainability of agricultural systems.

In tropical zones, high temperatures and abundant rainfall support crops like bananas, sugarcane, rice, and cocoa.

Temperate climates, with moderate rainfall and temperature variation, are ideal for grains like wheat, corn, and soybeans.

Arid and semi-arid zones require irrigation and are suited to drought-resistant crops such as millet and sorghum or livestock like goats and camels.

Highland climates support niche crops like coffee or tea, where elevation moderates temperature.

Farmers adjust practices to fit local conditions, including planting calendars, crop rotation, and irrigation methods, ensuring better yields and resource conservation.

Specialization is driven by a mix of environmental, economic, and cultural factors that make certain crops or animals more viable or profitable in specific regions.

Natural resources: Fertile soil, topography, and water access determine what can be grown successfully.

Climate: Long growing seasons or cool climates influence whether crops like rice, wheat, or grapes are more suitable.

Infrastructure: Regions with better transportation, storage, and processing facilities often specialize in commercial agriculture.

Market demand: High demand for a crop regionally or globally encourages specialization, like almonds in California or coffee in Ethiopia.

Cultural tradition: Long-standing practices influence what crops or animals are favored, such as rice in East Asia or sheep in New Zealand.

Government policy: Subsidies or export incentives can steer farmers toward certain production types.

Soil fertility is essential because it directly affects crop yields, influencing whether an area can support intensive agriculture or only subsistence or extensive practices.

High soil fertility, like that found in loess soils in China or mollisols in the U.S. Midwest, supports grain farming at commercial scales.

Regions with volcanic soils, such as parts of Indonesia or East Africa, are known for rich soil and diverse crop production.

Poor or degraded soils, common in tropical rainforests, often require shifting cultivation or heavy use of fertilizers.

Fertility is also managed through practices like crop rotation, fallowing, composting, and green manure to maintain productivity.

Soil health impacts the types of crops chosen, their success, and the long-term viability of agricultural systems.

Proximity to transportation networks like highways, railroads, ports, and airports influences what type of agriculture is practiced and how products reach markets.

Perishable crops like strawberries, dairy, and leafy greens are often grown near transport routes to ensure freshness and reduce spoilage.

Large-scale grain or livestock farms are located farther away, where land is cheaper, but rely on bulk transport like rail to access markets.

Remote areas with poor transportation often engage in subsistence farming or grow non-perishable crops like tubers or dried beans.

Investment in infrastructure can shift agricultural land use, allowing formerly isolated regions to integrate into national or global food systems.

Efficient transport reduces production costs, increases profit margins, and shapes how land is valued and used agriculturally.

Political conditions can significantly impact farming practices, food availability, and the ability of regions to function as stable agricultural producers.

In politically stable countries, consistent agricultural policy, land ownership rights, and infrastructure investments support commercial agriculture.

Instability can disrupt farming through conflict, displacement of farmers, or destruction of infrastructure like irrigation systems and roads.

War-torn regions may see abandoned farmland, food shortages, and declining exports.

Governments in stable regions may offer subsidies, crop insurance, and support services that boost farmer productivity.

In contrast, corruption, land disputes, or lack of regulation in unstable regions can deter investment and hinder sustainable land use.

As a result, agricultural output and trade potential vary widely based on the governance and legal structures in place.

Practice Questions

Explain how the bid-rent theory influences the spatial organization of agricultural activities around urban areas. Provide a specific example in your answer.

The bid-rent theory explains that land closest to the central business district (CBD) is more expensive due to its accessibility and desirability. As a result, high-value, perishable agricultural products like fruits, vegetables, and dairy are typically grown near cities to reduce transportation time and cost. Further from the city, where land is cheaper, less perishable and more land-intensive crops like grains or livestock farming dominate. For example, in California, market gardening occurs near Los Angeles, while wheat and cattle farming take place in the more remote Central Valley, aligning with bid-rent principles of land use efficiency.

Differentiate between intensive and extensive agricultural practices. Describe where each is most likely to occur and why.

Intensive agriculture involves high input and labor per unit of land and is most common in areas with high population density and expensive land, such as parts of East Asia and Europe. It includes market gardening and rice farming, which require constant attention and maximize yield. Extensive agriculture uses lower inputs over large areas and is suited to regions with abundant land and low population density, like cattle ranching in Australia or wheat farming in the Canadian Prairies. These practices reflect differing land availability, market demands, and economic conditions that influence how agriculture is spatially organized.