Urban changes driven by increasing population, economic shifts, and development pressures can create significant challenges in housing, equity, mobility, and the environment in cities.

Housing Affordability and Displacement

Rising Housing Costs

As cities grow and attract more residents due to employment, cultural amenities, and services, the demand for housing often outpaces the supply. This increased demand causes a sharp rise in property values and rental prices, a phenomenon especially pronounced in central urban areas and neighborhoods near business districts or transit hubs. For low- and middle-income families, the growing gap between wages and housing costs creates severe economic pressure. Individuals and families may be forced to relocate to more affordable, but less accessible, neighborhoods—further away from work, schools, and essential services. The problem of affordability often leads to housing insecurity, where people live in temporary, substandard, or overcrowded conditions. In extreme cases, this can result in homelessness, particularly among vulnerable populations such as the elderly, disabled, or those with unstable employment.

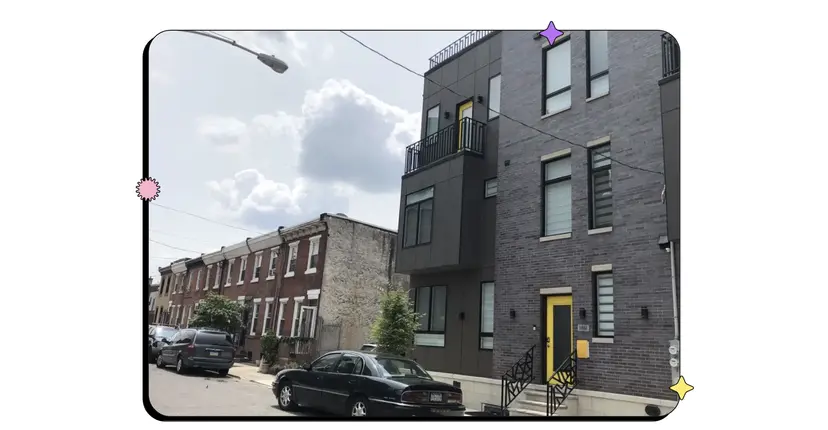

Gentrification

Gentrification is a complex and often controversial urban process. It begins when deteriorated or undervalued neighborhoods attract wealthier individuals or developers who renovate buildings, open new businesses, and invest in infrastructure improvements. These upgrades can increase the neighborhood's appeal and lead to higher property values. However, this also causes rising rents and property taxes, making it difficult for long-time, lower-income residents to remain in the area. As a result, gentrification often leads to displacement of these residents, particularly marginalized communities, such as racial and ethnic minorities. Additionally, the influx of new, wealthier populations may alter the cultural identity of the area, replacing local businesses, traditions, and landmarks with commercialized or upscale establishments. Tensions can grow between long-standing residents who feel excluded from the revitalized space and newcomers who bring different values and expectations.

Squatter Settlements

In many developing countries, squatter settlements—also known as informal settlements or shantytowns—are a direct consequence of rapid urbanization and the lack of affordable housing. These settlements often develop on the urban periphery or on land not legally designated for residential use. Residents build homes from scrap materials such as wood, tin, or plastic sheeting, and they frequently lack access to basic infrastructure like running water, electricity, sanitation, and paved roads. Life in these settlements is precarious: residents face constant threats of eviction, disease, and violence, and they typically have no legal recourse due to their informal occupancy. Despite the challenges, squatter settlements often develop complex social structures, local economies, and strong community networks. Governments and non-governmental organizations sometimes intervene through slum upgrading programs, which aim to formalize land rights and improve living conditions without displacing residents.

Social and Economic Inequality

Residential Segregation

Residential segregation refers to the separation of different groups into distinct neighborhoods, often along racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic lines. Segregation may result from intentional policies or from more subtle social and economic processes. In either case, it tends to reinforce inequality. Neighborhoods with predominantly minority or low-income populations often receive fewer public services, have lower-performing schools, and lack access to healthcare, employment, and safe recreational spaces. These inequalities can become self-reinforcing, as disinvestment in segregated areas leads to declining property values, fewer job opportunities, and increased crime. Residents in segregated areas face significant obstacles to upward mobility, and segregation limits social cohesion and integration within cities.

Redlining

Redlining is a discriminatory practice that emerged in the United States during the 1930s, where banks, insurers, and other financial institutions refused loans or services to individuals living in certain neighborhoods, primarily based on racial or ethnic composition. Maps were created to identify areas considered "risky" investments, and minority communities were often marked in red, hence the term. This practice effectively denied African Americans and other minorities access to home ownership, one of the most common ways to build wealth in the U.S. Although redlining was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its legacy persists. Formerly redlined areas still suffer from underinvestment, poverty, and deteriorating infrastructure, while historically favored neighborhoods continue to benefit from accumulated wealth and opportunity.

Blockbusting

Blockbusting was a manipulative real estate practice prominent in the mid-20th century. Real estate agents would spread rumors to white homeowners suggesting that racial minorities were moving into the neighborhood, warning that this would lead to falling property values. Fearing economic loss and social change, homeowners sold their homes at below-market prices. These homes were then resold at inflated prices to minority families, often using exploitative lending terms. Blockbusting contributed to white flight, racial segregation, and the destabilization of urban neighborhoods. It created a cycle of disinvestment and turnover, weakening community cohesion and degrading property values over time.

White Flight

White flight refers to the large-scale migration of white families from racially mixed urban neighborhoods to racially homogenous suburbs. This migration was driven by a combination of racial prejudice, fear of crime, declining urban schools, and the perception that suburban areas offered a higher quality of life. The exodus of middle-class white residents drained urban areas of tax revenue, weakening the fiscal base needed for public services such as education, transportation, and infrastructure. The loss of economic resources contributed to the decline of inner-city neighborhoods, compounding existing racial and economic inequalities.

Urban Infrastructure and Disamenity Zones

Disamenity Zones

Disamenity zones are areas within cities that lack access to amenities considered essential for quality of life, such as clean air, safe housing, green spaces, and reliable public transportation. These zones often arise in regions where urban decline, industrial pollution, and disinvestment intersect. Residents in these areas may experience high crime rates, unemployment, and exposure to environmental hazards such as toxic waste or industrial emissions. These zones are often home to the most vulnerable populations, including people of color, immigrants, and those living below the poverty line. Addressing disamenity zones requires targeted policy interventions, including urban renewal projects, public investment, and community development initiatives.

Public Housing Challenges

Public housing is a vital component of urban infrastructure, designed to provide safe and affordable shelter to low-income families. In practice, however, many public housing projects have faced serious challenges, including inadequate maintenance, poor design, and concentrated poverty. In some cities, public housing developments have become isolated pockets of deprivation, with high crime rates, low educational outcomes, and limited access to employment. The stigma associated with public housing can also discourage investment and limit residents' upward mobility. Modern housing strategies increasingly focus on mixed-income developments and housing vouchers, which aim to deconcentrate poverty and provide more choices for low-income households.

Source: The Philadelphia Inquirer

Master-Planned and Gated Communities

In response to urban challenges, particularly crime and overcrowding, master-planned communities and gated communities have become increasingly popular, especially among affluent populations. These communities are often built on the suburban fringe and feature carefully designed layouts, recreational facilities, and controlled access. While they offer security and amenities, they can also exacerbate social segregation, by creating enclaves of wealth disconnected from the broader urban environment. Gated communities may divert public resources away from more needy neighborhoods and limit opportunities for cross-class or multicultural interactions.

De Jure and De Facto Segregation

De Jure Segregation

De jure segregation refers to legal or officially mandated separation of groups based on race, religion, or other characteristics. In the U.S., de jure segregation was upheld by laws that created separate schools, transportation systems, and public facilities for white and Black citizens. Although most forms of de jure segregation have been outlawed, their legacy remains embedded in urban landscapes. Formerly segregated areas still reflect the historical inequalities in housing, education, and economic opportunity.

De Facto Segregation

De facto segregation, in contrast, occurs without legal enforcement. It results from residential choices, economic disparities, and social preferences. For example, when wealthier families choose to live in neighborhoods with better schools, or when discriminatory real estate practices subtly guide minority buyers to certain areas, the result is continued segregation. De facto segregation reinforces inequality and can be just as damaging as de jure segregation, limiting access to quality education, healthcare, and social mobility.

Traffic and Mobility Issues

Traffic Congestion

As cities expand, traffic congestion becomes a significant challenge. More people commute longer distances, particularly in car-dependent cities with limited public transportation. The result is slower travel times, air pollution, increased stress, and economic inefficiency. Congestion also affects emergency services, delivery logistics, and the overall functioning of urban systems. Efforts to reduce congestion include:

Expanding mass transit systems like buses and subways.

Implementing bike lanes and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure.

Encouraging carpooling and remote work options.

Introducing congestion pricing to discourage peak-hour driving.

Counter-Urbanization

Counter-urbanization is the movement of people away from cities to rural or exurban areas. This trend reflects dissatisfaction with urban problems such as noise, pollution, crowding, and high living costs. It also stems from technological advances that allow for remote work, making rural living more viable. While counter-urbanization can ease pressure on city infrastructure, it may strain rural resources, increase urban sprawl, and require new investments in transportation, utilities, and social services.

Environmental and Health Concerns

Environmental Degradation

Urban growth often comes at the expense of the environment. Construction, transportation, and industrial activity lead to the loss of green spaces, increased carbon emissions, and depletion of natural resources. Unchecked development can destroy ecosystems, worsen flooding, and degrade air and water quality. Mitigating these effects requires:

Implementation of sustainable planning practices.

Investment in green infrastructure like parks and permeable pavements.

Promotion of public transit and renewable energy sources.

Health Implications

Health disparities are closely linked to urban geography. Populations in poorer, high-density areas are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, mental health issues, and environmental illnesses. Limited access to healthcare, nutritious food, and clean environments compounds these issues. Addressing urban health requires comprehensive strategies, including:

Expanding access to healthcare facilities.

Promoting environmental justice in marginalized neighborhoods.

Designing cities to support active living and mental well-being.

FAQ

Large-scale infrastructure projects such as highway construction, stadium developments, or transit expansions can increase the risk of displacement in nearby urban neighborhoods, especially those with vulnerable populations. These projects often increase land values and attract new investment, which can raise property taxes and rents. Displacement occurs when longtime residents can no longer afford to live in the area or when their homes are demolished to make way for new development.

Infrastructure improvements may prioritize regional mobility over local needs.

Eminent domain can be used to forcibly acquire private property for public use.

Projects often disproportionately affect low-income and minority communities.

Without strong protections or relocation programs, infrastructure growth can worsen inequality.

Urban renewal involves the planned redevelopment of areas deemed “blighted” or underutilized, typically led by government initiatives. While it aims to modernize cities by replacing deteriorated buildings and revitalizing declining neighborhoods, it can also lead to displacement, similar to gentrification. However, urban renewal is more top-down and policy-driven, while gentrification is often a market-led process fueled by private investment.

Urban renewal projects may involve demolition of entire blocks for new construction.

It historically displaced thousands without adequate compensation or relocation plans.

Gentrification usually begins incrementally, house by house or block by block.

Both processes can alter the social fabric of neighborhoods and contribute to socio-spatial inequality.

Informal economies in squatter settlements thrive due to limited access to formal employment and legal restrictions on unregistered businesses. These economies include street vending, informal construction work, and unlicensed transport services. They help residents survive economically, but they also pose challenges for urban planners and governments.

Informal businesses often operate without regulation, making them difficult to tax or monitor.

These activities can contribute to unsafe working conditions and exploitation.

The lack of oversight can complicate public service delivery and law enforcement.

Despite their risks, informal economies support thousands of families and are essential to urban survival in many developing cities.

Disamenity zones are areas with poor living conditions due to environmental hazards, high crime, or a lack of public services, but they may still be inhabited. Zones of abandonment, on the other hand, are parts of cities that have been vacated or severely depopulated due to economic decline, often leaving behind derelict buildings and empty lots.

Disamenity zones require improvements in policing, sanitation, and healthcare access.

Zones of abandonment may need investment incentives to attract developers or residents.

Policies such as tax breaks, land banking, and community land trusts can promote revitalization.

Inclusive planning ensures existing residents are not displaced during redevelopment.

Gated communities are residential zones that restrict public access and often cater to higher-income populations seeking privacy and security. These communities contribute to spatial inequality by physically separating the wealthy from the urban poor, creating a fragmented urban landscape with uneven access to services and infrastructure.

Gated communities often receive better infrastructure, policing, and utilities than surrounding neighborhoods.

Their exclusivity can reduce social interaction and limit public accountability.

The concentration of wealth in these areas can reduce the political influence of lower-income communities.

As more resources are directed to these enclaves, public investment in less affluent areas may decline, worsening overall urban inequality.

Practice Questions

Explain how gentrification can simultaneously lead to neighborhood revitalization and social displacement. Provide one example of a potential outcome for each.

Gentrification revitalizes neighborhoods by attracting investment, renovating housing, and introducing new businesses, which can improve infrastructure and increase safety. However, it often leads to the displacement of long-term, low-income residents due to rising rents and property taxes. An example of revitalization is the development of new public spaces and amenities that benefit newcomers. Conversely, a negative outcome is the cultural loss when original communities are forced to relocate, breaking social networks and diminishing diversity. Thus, gentrification can improve urban aesthetics and services while exacerbating social inequality and contributing to residential instability.

Describe how redlining and white flight have contributed to residential segregation in American cities.

Redlining and white flight have played major roles in creating and maintaining residential segregation. Redlining denied mortgage loans to residents of minority neighborhoods, limiting homeownership and investment. White flight followed, as white residents moved to suburbs to avoid integration and perceived urban decline. This led to disinvestment in inner cities and wealth concentration in suburban areas. The result is a persistent spatial division by race and income, with minority communities often concentrated in under-resourced neighborhoods. These patterns reinforce inequality by limiting access to quality education, healthcare, and employment opportunities, perpetuating cycles of poverty and segregation.