Urban internal structure refers to the spatial organization of cities, shaping how land use, social groups, and economic activities are arranged.

Understanding Urban Internal Structure

The internal structure of cities refers to how different areas within urban environments are organized and used for various purposes such as residential living, commercial activities, industry, and transportation. This structure is not random—it is shaped by economic forces, planning decisions, geography, transportation systems, and cultural patterns. Studying internal structures allows geographers and planners to identify patterns in how cities grow and change over time. This also enables better decision-making in terms of zoning, transportation, and sustainability.

In AP Human Geography, analyzing these internal structures through different theoretical models helps students understand real-world urban development. These models aim to simplify complex urban forms into more manageable and comparable formats for analysis. They help illustrate the impact of human behavior, social hierarchy, and economic development on the built environment.

Importance of City Models

City models are theoretical representations that attempt to explain the layout of cities and the distribution of people and functions across urban space. While each model is a generalization, these frameworks are essential for identifying and comparing urban growth patterns across time and space.

City models help us:

Understand how urban functions like housing, retail, and industry are spatially distributed.

Analyze how socioeconomic status and race may influence residential location.

Examine how transportation networks shape city form.

Anticipate future urban development and challenges.

Assess zoning regulations and city planning strategies.

They are also useful in predicting urban change, explaining social segregation, and addressing issues like urban sprawl and traffic congestion.

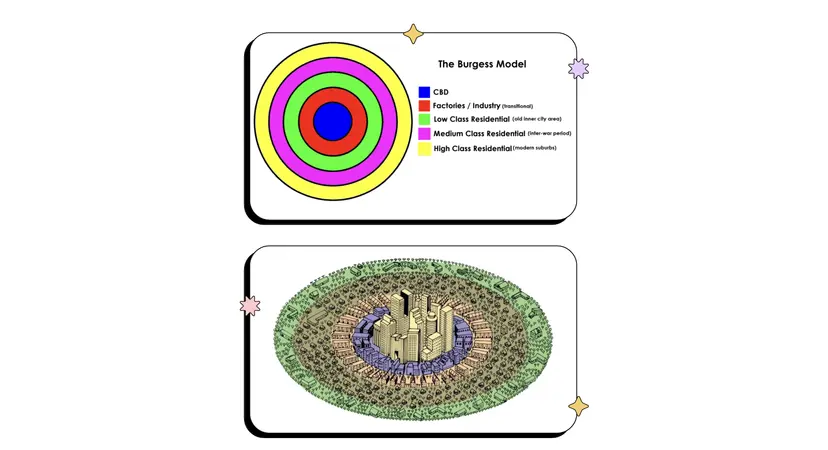

Concentric Zone Model (Burgess Model)

Developed by Ernest W. Burgess in the 1920s, the Concentric Zone Model was based on studies of Chicago. It was one of the earliest attempts to describe urban land use in a systematic way. This model visualizes cities as growing outward in rings or concentric circles from a central point, typically the Central Business District (CBD).

Key Zones of the Concentric Zone Model

Central Business District (CBD)

This is the economic heart of the city.

Includes offices, banks, government buildings, and retail stores.

Land values are highest here, and buildings are tall due to space constraints.

Transportation hubs are commonly located here.

Zone of Transition

Located immediately outside the CBD.

Characterized by deteriorating housing, mixed land use, and recent immigrant communities.

Often the site of light industry and warehouses.

Subject to processes of urban renewal and gentrification.

Working-Class Zone

Residential area for blue-collar workers.

Small homes, often with minimal green space.

Residents may live here due to proximity to jobs in the CBD or industrial zones.

Residential Zone (Middle Class)

Single-family homes with larger lots.

Improved infrastructure, lower crime rates.

Reflects higher socioeconomic status compared to the inner zones.

Commuter Zone (Suburbs)

Outermost ring, dominated by affluent residents.

Characterized by low-density housing and reliance on cars for commuting.

Includes shopping malls, schools, and recreational facilities.

Strengths of the Model

Introduced the idea that urban growth is patterned and measurable.

Applicable to early industrial cities in North America and Europe.

Limitations

Assumes a uniform, flat landscape without physical barriers.

Oversimplifies social dynamics and ignores ethnic enclaves.

Does not reflect modern decentralized cities with multiple business districts.

Image Source: ResearchGate

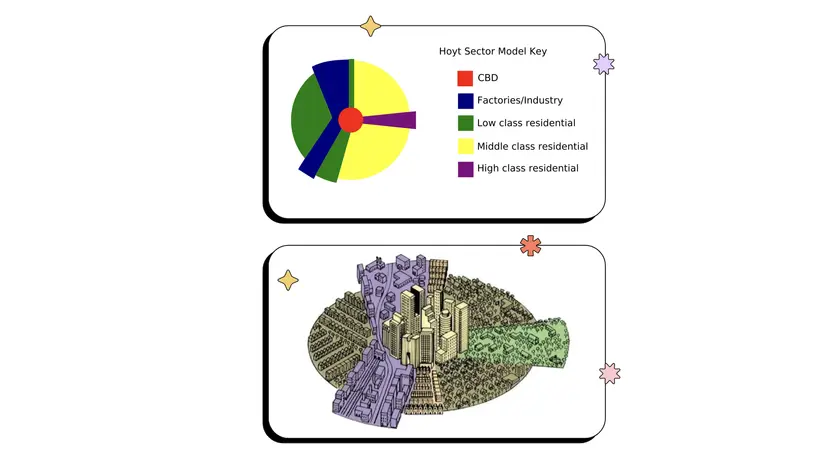

Sector Model (Hoyt Model)

The Hoyt Sector Model, developed by Homer Hoyt in 1939, built upon Burgess’s ideas but introduced the concept of sectors rather than concentric rings. Hoyt proposed that certain types of land use and social groups expand outward in wedge-shaped sectors from the city center, often following major transportation routes.

Features of the Hoyt Sector Model

The CBD remains the focal point.

High-income residential areas develop in wedges extending from the CBD along desirable transportation corridors.

Industrial sectors follow rail lines or highways, avoiding high-income residential zones.

Lower-income housing is found near industrial zones and transportation networks due to affordability and job access.

Land Use Sectors

CBD (Central Business District) – still the economic core.

Industrial/Transportation Sector – located near railroads and highways.

Low-Class Residential Sector – adjacent to industrial zones.

Middle-Class Residential Sector – forms a buffer between lower and upper-class zones.

High-Class Residential Sector – located farthest from industrial zones, along scenic routes or commuter lines.

Advantages

Highlights the role of transportation and economic status in shaping city growth.

Better reflects urban development along transit corridors than the Burgess model.

Disadvantages

Still assumes a single urban core.

Fails to account for multiple business districts or the rise of edge cities.

Oversimplifies spatial segregation caused by race or ethnicity.

Image Source: ResearchGate

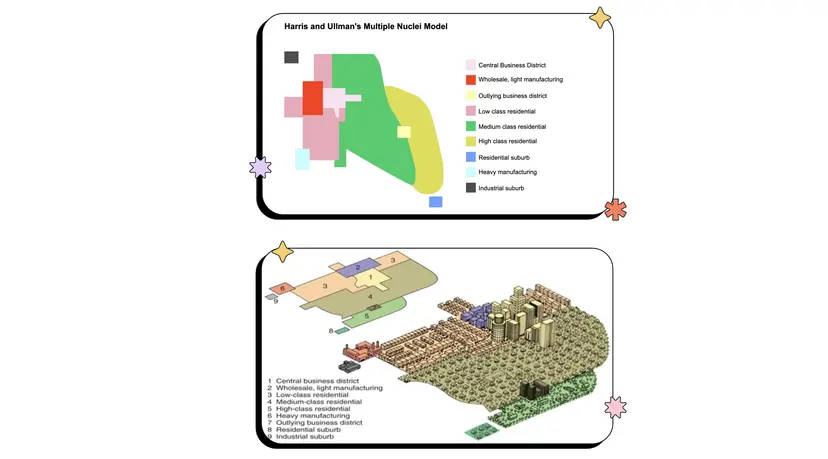

Multiple Nuclei Model

Proposed in 1945 by geographer Chauncy Harris and economist Edward Ullman, the Multiple Nuclei Model suggests that cities do not grow around a single CBD but rather develop around multiple centers or "nuclei." Each nucleus serves as a hub for specific activities, such as retail, manufacturing, or education.

Major Concepts

Land uses with similar needs group together in specific locations (e.g., universities and bookstores).

Incompatible land uses are separated (e.g., residential neighborhoods and heavy industry).

Nuclei develop based on different factors such as land cost, accessibility, and function.

The CBD still exists but is no longer the sole focal point.

Example Nuclei

Downtown CBD – traditional hub of commerce and finance.

Industrial parks – located near rail lines or ports.

Suburban retail centers – malls and shopping districts outside the CBD.

University district – includes academic buildings, housing, and cafes.

Business hubs – satellite centers for office buildings and services.

Applications

Helps explain urban growth in larger, post-industrial cities.

Accounts for urban sprawl, diversified economies, and automobile dependency.

Criticisms

Does not specify the shape or number of nuclei.

Requires detailed local knowledge to apply effectively.

Still limited in addressing racial segregation and housing inequality.

Image Source: ResearchGate

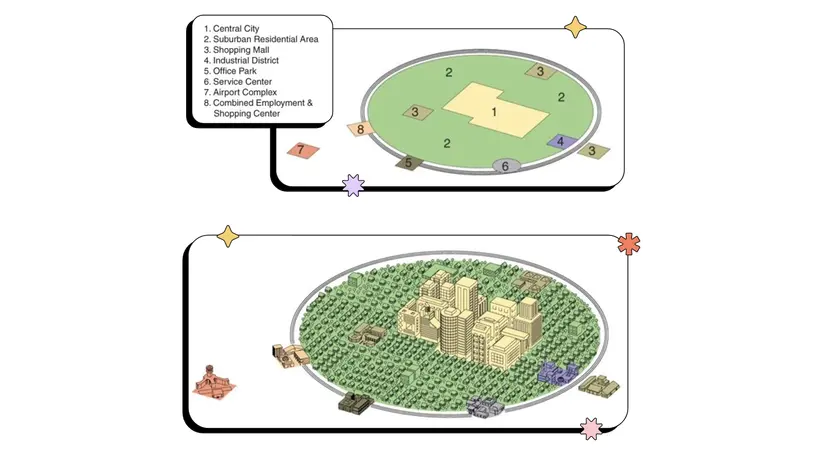

Peripheral Model (Edge City Model)

The Peripheral Model, influenced by the ideas of journalist Joel Garreau, describes urban expansion into "edge cities"—new urban centers located on the periphery of traditional metropolitan areas. This model reflects the reality of decentralization and the rise of suburban economic hubs.

Characteristics of Edge Cities

Located at major highway intersections and near airports.

Built around retail centers, office parks, and entertainment complexes.

Typically car-dependent, with low walkability and little public transit.

Mixed-use developments: residential, commercial, and light industrial.

Functions

Provide jobs, shopping, and amenities, reducing the need to travel to the traditional CBD.

Often self-sufficient, functioning as economic zones in their own right.

Examples include Tysons Corner, VA and Irvine, CA.

Social and Economic Impacts

Improves accessibility for suburban populations.

May weaken the economic power of the historic CBD.

Contributes to urban sprawl, increased traffic congestion, and environmental degradation.

Drawbacks

Encourages socioeconomic separation.

Lacks the cultural and social vibrancy of traditional downtowns.

Creates challenges for regional planning and infrastructure development.

Image Source: ResearchGate

Real-World Urban Structures

Chicago, Illinois

Classic example of the Concentric Zone Model.

Shows zones transitioning from CBD to industrial and residential use.

Los Angeles, California

Reflects the Multiple Nuclei Model with several distinct commercial and cultural hubs.

Atlanta, Georgia

Strongly shaped by the Peripheral Model, featuring sprawling suburbs and edge cities along I-285.

Urban Planning and Internal Structure

Urban structure is influenced not only by organic growth but also by intentional planning. Key planning tools include:

Zoning Laws

Regulate land use by designating areas as residential, commercial, industrial, etc.

Prevent incompatible uses from co-locating (e.g., factories next to homes).

Transportation Networks

Highways, rail lines, and public transit guide urban expansion.

Accessibility increases land value and desirability.

Housing Policies

Government subsidies, rent control, and housing development plans affect where people live.

Can reinforce or reduce spatial segregation.

Urban Renewal and Gentrification

Redevelopment projects often revitalize aging urban areas.

May lead to the displacement of lower-income residents and changes in neighborhood character.

Key Terms

Burgess Model: A concentric zone model with five rings illustrating urban growth.

CBD (Central Business District): Core area of economic and business activity.

Hoyt Sector Model: Emphasizes urban expansion along transportation routes.

Multiple Nuclei Model: Proposes that cities grow around several centers of activity.

Peripheral Model / Edge City: Reflects suburban economic centers outside traditional downtowns.

Urban Sprawl: Low-density, car-dependent development on city outskirts.

Zoning: Government regulations that determine land use types and locations.

FAQ

Physical geography significantly impacts the layout and internal structure of cities, shaping how land is used and developed over time. Unlike the abstract models that assume flat, featureless land, real-world cities must adapt to their environment.

Rivers and coastlines often dictate the placement of CBDs and industrial zones, providing access to trade and transport.

Hills and mountains may act as barriers, leading to irregular growth and shaping where residential or commercial areas develop.

Floodplains and wetlands may limit construction or push development to higher ground.

In cities with rugged terrain, zoning patterns are often fragmented, creating asymmetric urban layouts that deviate from standard models.

Social segregation in urban areas often results from historical policies, economic disparity, and cultural divisions. It affects how people are distributed spatially within a city.

Lower-income populations often cluster in older housing near industrial zones or within the zone of transition.

Wealthier groups are typically located in suburban or peripheral zones with access to amenities and cleaner environments.

Racial or ethnic enclaves can emerge, especially in cities with a history of immigration or discriminatory housing practices.

Infrastructure quality, public services, and environmental conditions often vary dramatically between zones, reinforcing segregation and social inequality across the urban landscape.

Most traditional urban models, such as the Burgess or Hoyt models, were based on Western cities and don’t adequately explain urban forms in developing regions, especially the presence of informal settlements.

Informal settlements often emerge on the periphery or in hazard-prone areas like hillsides or floodplains.

They result from rapid urban migration and a lack of affordable housing.

These areas may lack formal infrastructure like sewage, electricity, or roads.

Over time, some informal settlements undergo regularization, gaining official recognition and services.

In developing cities, urban planners often adapt or modify models like the Latin American City Model, which explicitly includes zones for informal housing.

Land value is a critical factor in determining urban land use and development intensity. Higher land value areas are generally developed more densely and used for more profitable functions.

The CBD usually has the highest land values due to accessibility and visibility, leading to vertical development (e.g., skyscrapers).

As distance from the CBD increases, land value typically decreases, making lower-density housing more feasible.

Commercial zones are often located along high-traffic corridors to maximize exposure and profit.

Industrial uses tend to occupy land where values are moderate and access to transportation is convenient.

Planners use land value assessments to guide zoning, tax policy, and infrastructure investment.

Historical events and planning decisions leave lasting marks on urban form, often determining the spatial arrangement of land uses and population groups even centuries later.

Cities with colonial histories often have grid layouts and central plazas inherited from European urban planning styles.

Industrialization created central factories surrounded by worker housing, some of which persists today.

Redlining and racially restrictive covenants in the 20th century led to long-term segregation, still visible in residential patterns.

Old transportation routes, like streetcar lines, shaped early suburban expansion.

Urban renewal and highway construction projects of the mid-1900s often displaced communities and redirected development.

These historical legacies help explain why many cities do not perfectly fit theoretical models.

Practice Questions

Explain how the Multiple Nuclei Model differs from the Concentric Zone Model in representing the internal structure of cities.

The Multiple Nuclei Model differs from the Concentric Zone Model by proposing that cities grow around several centers of activity, rather than outward from a single central business district (CBD). While the Concentric Zone Model depicts cities as expanding in rings with clearly defined zones, the Multiple Nuclei Model suggests a more complex urban layout where nodes of commerce, industry, and residence develop independently. This model better reflects post-industrial urban development, where specialized districts arise based on accessibility and land use compatibility. It acknowledges diverse urban functions and decentralization, especially in large, automobile-dependent metropolitan areas.

Describe how transportation networks influence urban structure according to the Hoyt Sector Model.

According to the Hoyt Sector Model, transportation networks such as railways and highways play a central role in shaping urban land use. Cities develop in wedge-shaped sectors radiating from the central business district, with specific land uses aligning along transportation corridors. High-income residential areas often grow along commuter routes, while industrial sectors follow freight lines and major roads. This pattern allows for efficient movement of goods and people. The model emphasizes the spatial influence of transit access, showing how economic activities cluster where accessibility is greatest, and how transportation shapes the distribution of social classes and land values.